Effective energy pricing is key to transitioning away from fossil fuels. Americans are not always great at following rules but we are excellent at following prices. If we align our pricing with the transition we need to see, then we will see it. If we don’t, we won’t.

Crowds flock to sales at Macy’s on Black Friday. Image source: Department of Energy

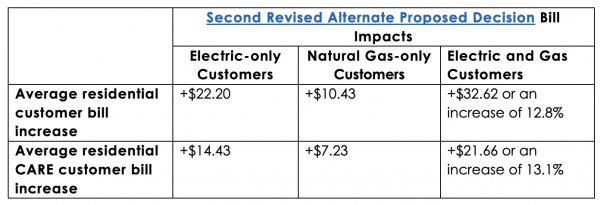

California’s electricity rates have a lot of problems right now. First of all, they are too high. Not just as in “they seem too high” or “they are higher than everyone else’s” (both of which are true), but also as in they are too high per economic theory. The actual cost of adding one more kWh of electricity to the grid is much less than the per-kWh rate we are charged. That means we are using too little electricity. I wrote about this in 2021 and our rates have only gone up since.

The power prices charged by California’s three investor-owned utilities, shown in orange for SDG&E, PG&E, and SCE (left to right), are higher than those of any in the western states. Source: California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

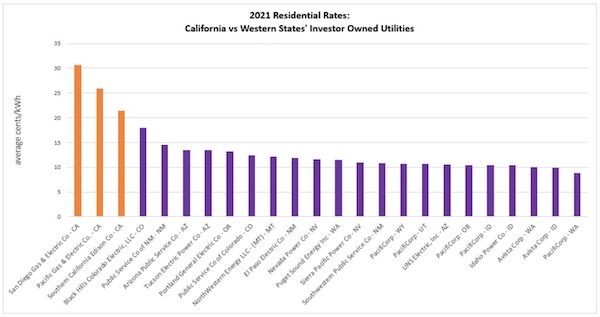

It’s not just that our prices are too high. The pricing is also unfair, making electricity unaffordable for many low-income households, even with the CARE and FERA discounts. (1) Although these discounts are used by 25% of customers, CARE participants make up 37% of the households that are behind on bills.

Customer arrears data for California’s investor-owned utilities, cumulative through 2023. Source: California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

The pricing is also far too inflexible. Electricity costs vary significantly over the day and over the year, yet the rates do little to reflect that. The result of this faulty pricing is that we use too much gas, too little electricity, and too much dirty electricity during times of peak demand.

Economists at the Energy Institute at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business have done a lot of work on this (see for example this writeup) and California’s legislators have been listening. California Assembly Bill 205, which was signed into law in June 2022, directs the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to develop an income-graduated fixed charge to improve affordability and speed up electrification, and to look into more flexible rates that will encourage use of cheaper and cleaner energy. That effort is now underway. (2) (Note: These rulings will not directly impact Palo Alto’s pricing, since it operates its own utility.)

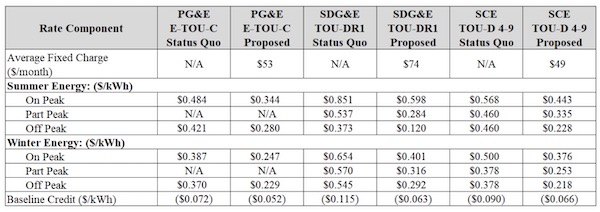

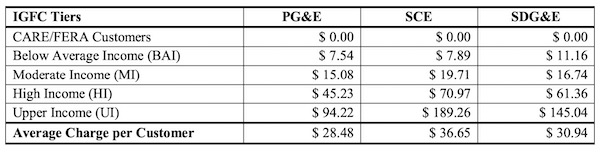

The basic idea behind the fixed charge is simple. If a utility collects more revenue in fixed charges, then it can offer lower per-kWh rates. Lower rates encourage electrification. The fixed charge can also make bills more affordable if it is income graduated. That is more or less what AB 205 asks for. Several variations have surfaced during the CPUC proceeding.

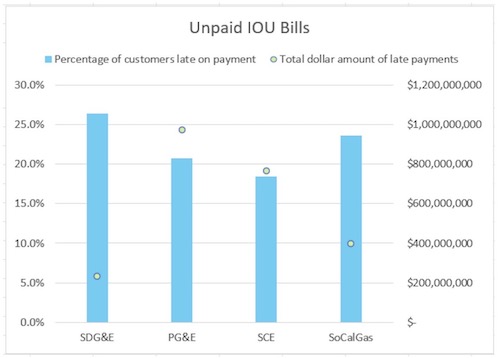

The three investor-owned utilities (IOUs) collaborated on a joint proposal. They are eager to make this happen, saying that “This residential rate reform is overdue and is needed now.” They suggest a substantial fixed charge that will lower rates by an average of 37%. To adjust the fixed charge by income, they specify four income levels. These use the federal poverty level as a benchmark to align with the guidelines for CARE and FERA discounts.

Investor-owned utilities suggest four income brackets based on Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The FPL is $30,000 for a family of four. CARE and FERA discounts are available to households earning less than 250% of FPL. Source: Testimony by the IOUs (2023)

The rates go down significantly, as shown in this chart.

Investor-owned utilities propose a substantial decrease in per-kWh rates. Source: Testimony by the IOUs (2023)

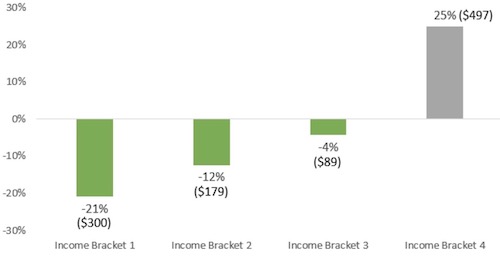

The IOUs tout the more affordable bills that come with the income-graduated fixed charge. The highest income bracket will pay more in bills, but still an affordable percentage relative to household income.

The average annual bill drops for the lowest three income brackets and goes up for the fourth, in the proposal offered by the Investor-owned utilities. Source: Testimony by the IOUs (2023)

The IOUs emphasize that all households will save money when they electrify because of the much lower rates. For example, they estimate that a moderate-income PG&E customer would save almost $1800 per year compared with today if they fully electrified.

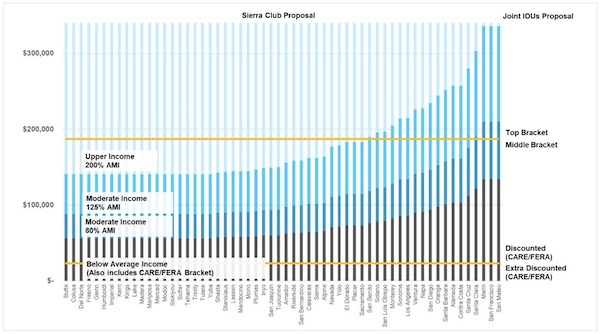

The Sierra Club believes that the IOUs are charging low-income households too much, and has come up with a different, more progressive proposal, charging $0 for all CARE/FERA customers, regardless of income. Moreover, they understand that “high” incomes are not so high in counties with a high cost of living. “Electric affordability is an issue that affects not only CARE/FERA customers, but a wider segment of the population affected by elevated cost of living in California.” So they base their five income levels on the Area Median Income (AMI) which, unlike the Federal Poverty Level, takes local cost of living into account.

The Sierra Club defines five income tiers based on Area Median Income (AMI) BAI: below 80% AMI. MI: below 125% AMI. HI: below 200% AMI. UI: above 200% AMI. AMI in Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties is around $165,000 for a family of four. Source: Testimony by the Sierra Club (2023)

The Sierra Club boasts that “most California customers would have substantially lower average monthly bills” if their proposal is adopted, and that theirs “is the only proposal to provide a substantial bill reduction (19%) for non-CARE/FERA customers with below-average incomes.”

Sierra Club’s location-sensitive income brackets, based on Area Median Income, are shown in colored bands. They allow for much greater income levels in expensive counties than the IOU’s statewide brackets based on the Federal Poverty Level, shown as horizontal yellow lines. Residents of Santa Clara, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo counties need household incomes over $300,000 to qualify for Sierra Club’s top bracket (and highest fixed charge). Source: Testimony by the Sierra Club (2023)

The Sierra Club explains that “The Joint IOUs’ top bracket unreasonably groups some customers making very close to average incomes in their counties with customers making well above average incomes. A (fixed charge proposal) that treats customers identically in a state with as much economic diversity as California runs counter to the intent of AB 205.”

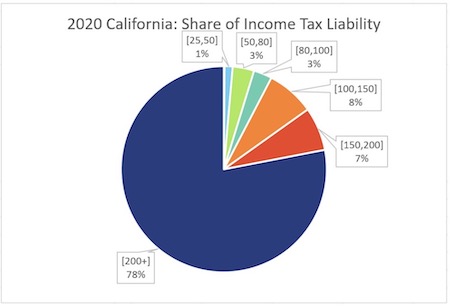

The California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA) takes this focus on a progressive rate structure even further. They reason that since the top earners in California have by far the largest income, then they should be paying even more.

Income in California is concentrated among the top earners. 78% of income comes from the 8.3% of households bringing in $200,000 or more. Source: Testimony by the California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

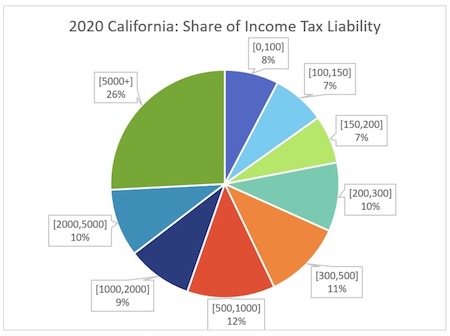

They look at income tax liability in nine different tiers of approximately equal size and create brackets accordingly.

The top bracket, consisting of the 0.1% of households with incomes over $5 million, represents 26% of income in the state. Source: Testimony by the California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

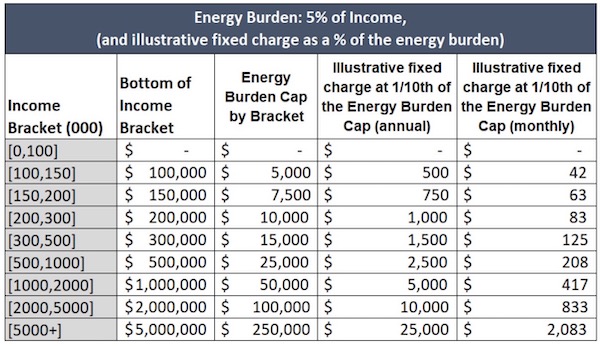

To keep prices equally affordable at all income levels, CEJA proposes a much higher fixed charge for the top brackets. As a thought experiment, they ask: “If a 5% energy burden is reasonable for low-income customers, should 5% not also be reasonable for high-income customers especially when considering the construction of a legislatively mandated income-graduated fixed charge?” In practice they say charges would not be at that level, but they provide this chart to convey the idea.

In this example, which sets an “energy burden cap” at 5% of income, the top income bracket representing households with more than $5 million in income would pay a fixed charge of $2,083 per month. Source: Testimony by the California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

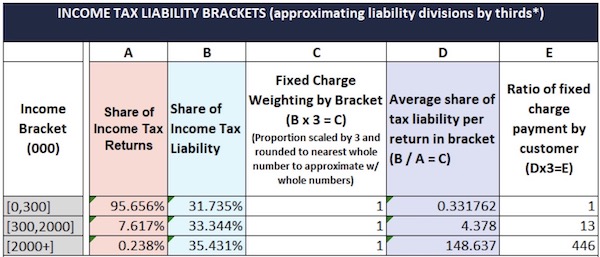

If nine brackets is too many, they suggest what three might look like, again choosing them based on equal tax liability.

In this example, one-third of the revenue would come from each bracket, with the lowest bracket representing incomes up to $300,000 and the middle bracket incomes up to $2 million. Source: Testimony by the California Environmental Justice Alliance (2023)

Unfortunately the analysts at California Environmental Justice Alliance were not able to work out the needed level of fixed charges for each bracket because the modeling tool the CPUC provided did not support brackets beyond $200K. As a result, CEJA was only able to specify the ratios across income levels.

Some of the other parties struggled with this model. Doesn’t it become vulnerable to the incomes of a few households? What if those wealthiest households defect from the grid? The investor-owned utilities say that this model and the Sierra Club’s are too complex and won’t work for high-income households. “These two proposals could be perceived as purely punitive by higher income customers due to the lack of perceivable benefit from reduced volumetric rates, therefore resulting in significant utility administrative and customer burden costs for little policy benefit.”

The solar industry, represented by the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), goes in a completely different direction. Their industry relies on high electricity rates to justify the expense of installing rooftop solar. So they propose a miniscule fixed charge with almost no impact on rates and instead suggest focusing on more time-differentiated rates that encourage flexible demand.

Almost every other party spent considerable space pointing out the ways in which this proposal does not achieve the goals set by AB 205. The Sierra Club says that "SEIA’s proposal does not reflect the statutory intent to revise rates in a manner that more aggressively pursues California’s electrification and equity goals." The investor-owned utilities write that “SEIA’s proposal is not compliant with the letter of AB 205 by any interpretation.” The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) writes that “SEIA’s proposal and recommendations are based on inaccurate rate design theory and should be rejected.” It seems like patience is wearing thin with the solar industry in these proceedings.

The last proposal I will reference is a joint proposal from NRDC and The Utility Reform Network (TURN), an advocate for ratepayers. They split the difference, coming in between most of the other proposals, making some compromises but achieving the essence of what AB 205 calls for.

They advocate for modest fixed charges based on three income levels. Rates go down in their scheme, but not to the degree that they go down for the IOUs. Affordability improves, but not as much as it does with the Sierra Club or CEJA proposals. Bills go up for higher-income customers, but electrification can save them money. “Coastal high tier customers for each IOU generally more than double their savings under our new electrification rate proposal relative to the existing rate.” NRDC and TURN seem to be aiming for something that will make things better, be politically palatable, and not be too hard to implement.

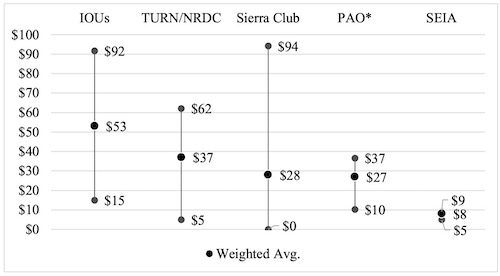

The proposed fixed charges vary as shown below. The investor-owned utilities propose the highest, while the solar industry proposes the lowest. The Sierra Club proposal has the lowest charges for lower-income households.

The fixed charge sizes and ranges, shown here for PG&E, vary across proposals. The CEJA proposal is not shown because the modeling tool was unable to implement their proposal. The Public Advocate Office’s plan shown here (PAO) is not covered in this blog post because unlike the other proposals it is not self-funded, so it is not really comparable. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

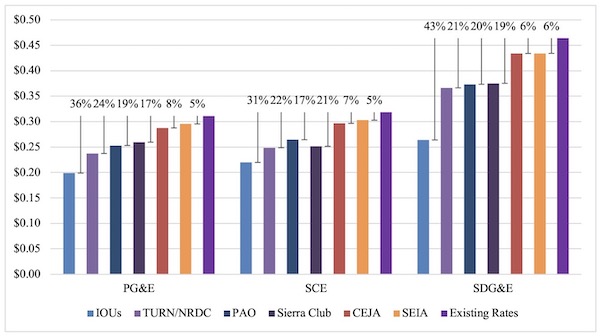

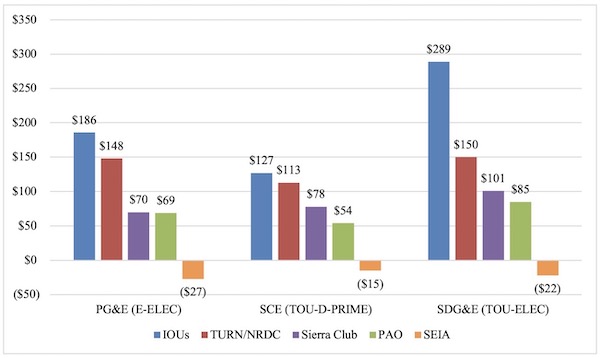

The proposed rate reductions are shown below, with the greatest reductions proposed by the investor-owned utilities and the lowest by the solar industry. (The CEJA proposal shown here is a modification that fits into the $200K limit of the tool, and is not one that CEJA recommends.)

Rate reductions proposed by each party, shown for each of the three IOUs. The IOU proposal suggests the biggest reductions (along with the greatest revenue from the fixed charges), while the solar (SEIA) proposal offers the smallest reductions. Again, the CEJA proposal shown here is not the one that they recommend, it’s only the version that could be modeled by CPUC’s tool. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

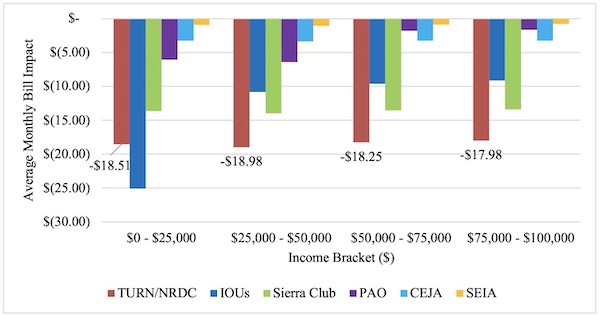

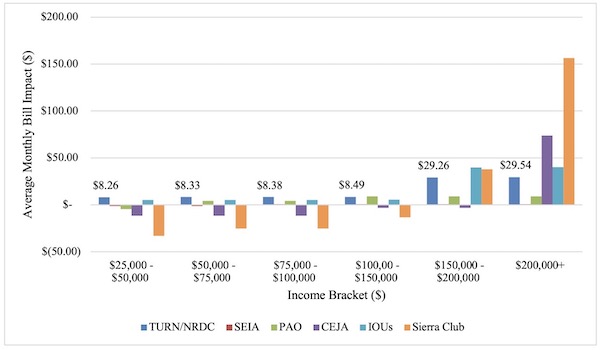

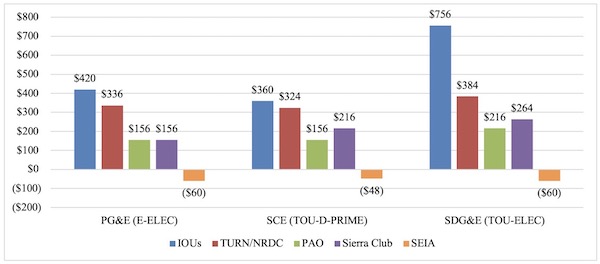

In all cases bills go down for low-income households and up for high-income households, but much more for some plans than others.

Average monthly bill impacts for CARE PG&E customers by income level and party proposal. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

Average monthly bill impacts for non-CARE coastal SCE customers by income level and party proposal. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

The lower rates mean that electrification becomes a better deal, for all proposals except that from the solar industry.

Annual savings on electric space and water heating operating costs for coastal customers earning $150,000. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

Annual savings on EV fueling costs for customers earning $150,000. Source: Testimony by NRDC and TURN (2023)

CEJA sweetens the deal for electrification, adding upside for high-income households, by suggesting that any household that fully electrifies by a certain date could get a $0 fixed charge (or 50% discount if more than $500,000 income).

There is a lot of discussion around implementation and how to assess income with enough accuracy. Some parties suggest letting customers self-report and doing random spot checks. Others prefer integrating with the state’s Franchise Tax Board, though that will take longer. Others suggest working with credit agencies. For the first phase, the CPUC has asked each party to come up with a plan that uses only the existing verification mechanism based on Federal Poverty Level.

There is also a good discussion about whether to account for the large disparities in cost of living across counties. The Sierra Club thinks this is important, as do Senator Josh Becker and Assemblyman Marc Berman. The investor-owned utilities are not so keen. They reason that not only would it be inconsistent with how we determine rates and CARE and other program qualifications today, it is not necessary. “The extent to which there are income differences between baseline territories is likely due to higher demand for housing in cooler coastal regions resulting in lower-income households being forced to live elsewhere. The fact that housing costs are extremely high in San Francisco compared to Stockton is not a reason to provide low-income electric bill discounts to six figure income households in San Francisco.”

But there is also a lot of agreement. Few disagree with the basic ask from the commission. As NRDC/TURN say, “The Commission is justified in setting fixed charges at a level that results in volumetric rates that encourage beneficial electrification, lead to progressive outcomes, do not adversely affect affordability, and maintain a signal for energy efficiency and conservation.”

A fixed charge is just the beginning. There is a parallel effort to develop more flexible pricing. But even more important is finding ways to reduce overall costs. Becker and Berman, as well as most of the parties in this proceeding, say that costs have to come down, for example by decreasing the return on equity that utilities receive and by funding social programs outside of electricity rates. The NRDC/TURN proposal contains a fairly depressing stat in this regard. Their proposal reduces rates by 20-25% from today’s pricing structure. And yet “recent rate increases have been so steep that the TURN/NRDC fixed charge proposal reduces volumetric rates to what they were between 2020 and 2022 in the PG&E and SDG&E service territories. These new reduced volumetric rates would still be among the highest in the nation.” Ugh.

I’d love to hear any questions or comments you have about this effort to overhaul California’s electricity pricing.

Notes and References

1. CARE = California Alternate Rates for Energy. These customers who generally earn less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Level, receive a 30-35% discount on electricity bills. FERA = Family Electric Rate Assistance. These customers, who earn less than 250% of the Federal Poverty Level, receive an 18% discount on electricity bills.

2. The way the process generally works is as follows. The CPUC invites thoughts on a topic (e.g., what does the law mean, what principles should we adopt for rate design, how big should the fixed charge be), and asks interested parties to submit testimony (e.g., proposals) by a certain date. These are published so that others can read them, and a “Reply” date is set for parties to comment on other proposals. You can see some of those submissions and replies here (under “Track A Opening Testimony”) and many others on the docket (see for example documents submitted on October 6.)

It is a productive process with a robust exchange of ideas. A CPUC administrator (an “Administrative Law Judge”) oversees the proceeding, setting guidelines for the proposals, answering questions, and ultimately determining the result. In this case, the judge has asked parties to comment on topics ranging from income thresholds to pricing rationale to implementation cost and complexity, to impact on electrification, and so on. A schedule for this back and forth has been outlined and is set to lead to a proposed decision in March or April of next year.

Current Climate Data

Global impacts (September 2023), US impacts (October 2023), CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Miscellaneous fact: More than half the CO2 emissions of the industrial age have been dumped into the atmosphere since 1990.

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.