Foothill College has a decision to make. Last summer the school was forced to close its pool due to a substantial leak. A subsequent investigation found that the underground pipes supplying water to the 63-year-old pool were cracked and offset. Replacing the pipes would mean ripping up both the pool deck and the pool shell, so Foothill staff envisioned a larger improvement. The updated facility will have a new Olympic size pool, expanded locker room, and improved accessibility. It is a vision that the board, students, faculty, and community at large are eager to see come to fruition.

Foothill College’s pool will no longer have a T shape. Image source: Wikimedia

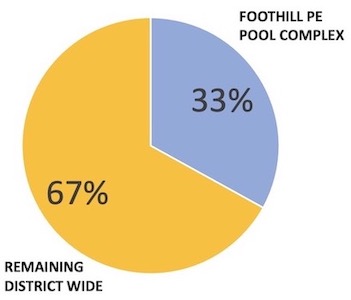

But one big question remains. Should Foothill heat the pool water with gas boilers or electric heat pumps? The old pool produced one-third of the campus' emissions. That is a significant amount, making this a unique opportunity to substantially reduce Foothill’s emissions.

The old pool accounted for one-third of the campus' Scope 1 emissions. Source: Presentation to Foothill Board of Trustees, September 2023

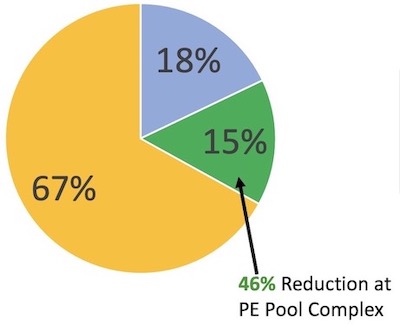

The new facility will use pool covers, which will reduce the heating requirement (and emissions) by 40%. If the school opts to use gas, the pool will use efficient condensing boilers, which will further reduce emissions. This setup is similar to that used at other large aquatic facilities in California today (Stanford, Berkeley, etc), and would reduce pool heating emissions by a total of 46% and overall district emissions by 15%. That is substantial.

The gas-based plan will reduce pool emissions by 46%, with most of that coming from the adoption of pool covers. After the renovation, this single gas-heated pool would then produce 21% of Foothill campus' Scope 1 emissions. Source: Presentation to Foothill Board of Trustees, September 2023

A 46% reduction sounds good. But in January of this year, Foothill College released its Sustainability Action Plan, which includes the objective to “Transition to natural gas-free by 2035”. As board member Peter Landsberger pointed out, it seems that installing gas boilers with a lifetime of 25 years is in conflict with this goal.

The board had its engineering consultant, Gayner, evaluate several all-electric designs. They came up with a workable design, but stated that it would almost double the cost of the project from $22M to $41M, and require considerable attention to operate and maintain due to its complexity. The firm also raised concerns about the impact of power outages, the space needed to accommodate the 20 or so heat pumps, and the sound emitted from those heat pumps, which will run much of the day and night.

Disappointed with Gayner’s findings, the board hired engineering firm Salas O’Brien to do a peer review of the analysis. The second review generally agreed with the first, though they also suggested evaluating a hybrid heating option using both gas boilers and heat pumps.

Dennis Berkshire, President of the Aquatic Design Group, spoke at Foothill’s August board meeting where they discussed the gas vs electric decision. His firm has worked on 75-80% of all large public pools in California, including the nearby Rengstorff Aquatic Center in Mountain View, which will be all-electric. Berkshire suggested that the gas boiler design is indeed the best option for Foothill. “In today’s world, the desire for electrification has outpaced industry and what’s currently available on the market.”

The Vice Chancellor for Business Services of the Foothill-DeAnza College District, Susan Cheu, has been following this closely. “I think it’s important to note that we were not happy about the outcome of not being able to use all-electric.” She explained that this is why they had the peer review done and went to the trouble of evaluating several other options. “At the end of the day, there’s some pragmatism that has to go into these projects.”

And yet.

In the Bay Area alone, there are four large outdoor all-electric pools in development (approved, funded, and under way). There is the Rengstorff Aquatic Center in Mountain View, the Belle Haven pool in Menlo Park, the Piedmont Aquatic Center, and a new aquatic center in South San Francisco. (1) Blake Herrschaft, the Building Electrification Programs Manager for Peninsula Clean Energy, reeled off this list and added that Peninsula Clean Energy is helping organizations like these find ways to cover the excess costs that may be involved in going all-electric. Clarence Mamuyac, President of the design firm ELS that is working on these all-electric pools, reported that the excess cost for going electric has been on the order of $1-$2 million for these projects.

I asked Mamuyac what might be different about Foothill, and he said he can’t say as he doesn’t know the details of the project. Could it be the size of the pool? (Olympic pools are very large.) He said it’s certainly possible, though he noted that the surface area of the two pools at each of Rengstorff and Piedmont (10,000-11,000 square feet) approaches that of an Olympic pool (13,500 square feet). Both of those projects are using 20+ heat pumps, similar to what Foothill’s design calls for. Berkshire mentioned when he spoke to Foothill’s board that the reliability requirements for a recreational pool like Rengstorff are not as strict as those for Foothill. It’s “not the end of the world” if the pool is unavailable for some reason. (2) He added that at Mountain View, their commitment to their carbon reduction goals was paramount. “In the case of the city of Mountain View, the city came back and said that they have a city ordinance for electrification. They chose to hold themselves to it at this facility…. Now in that case they decided to go all-electric, and in doing so, the capital costs and operating expenses were never discussed. It was simply saying ‘This is the right thing to do and we’re going to move ahead.’” (3)

The Board of Trustees at Foothill seems frustrated with the situation. Landsberger views the objectives in the Sustainability Action Plan, which they approved after years of work, as a commitment. “Are we essentially repealing our climate objectives? I want to know if we are doing that.” Cheu views it differently: “They are goals, and they are sort of an aspiration that we are trying for.” Board Chairman Patrick Ahrens sounded frustrated: “I’ve seen so many of these bodies have these aspirational goals and fly right by them,” but then went on to suggest that they might be better off focusing on transportation emissions.

On Monday September 11, District staff are proposing to move ahead with the gas boilers. They cite the complexity and risk involved with being early adopters of this technology in our area, as well as concerns about availability and noise.

Regarding that risk, Cheu reflected during the August board meeting, when this proposal first surfaced: “It wasn’t just a fiscal decision. Also what plays around in the back of our mind is the Sunnyvale Center. We did try new technology there and it didn’t, as you know, work out so well. That is something that is sort of also guiding our decision-making process through this. We want to make sure that whatever we put in there is not only going to be sustainable, but it is going to work, is going to do what it needs to do, and is going to be something we can maintain.”

There is undoubtedly risk involved in being an early adopter. While these technologies aren’t new, using them for large outdoor pools in the Bay Area is new, and we have a critical lack of expertise with deploying this type of efficient electric heating here. Consider what happened with the Sunnyvale Center’s hydronic HVAC system. Some rooms were too hot and some were too cold. An engineering consultant told Foothill that they needed to replace the entire system, with the possible exception of the radiant pipes, and the school did. But I’ve heard of this problem in other contexts, for example when a refrigerant with a high temperature differential is used. In Europe they will sometimes toggle the direction of such circuits so that no room stays cold or warm. Would that have been an option here? I don’t know.

The point is, we have a dearth of skilled engineers and tradespeople in the Bay Area who can design, implement, and tune efficient electric heating systems like this. What better place than Foothill College to start addressing that skill gap? Foothill is the top-ranked community college in all of California, and one of the top in the entire nation. The primary purpose of Foothill College is to educate and to train, to help students develop the skills needed in the future. It has passionate faculty and an energized student body. Should a school like that duck this challenge or lean into it? Stanford has been innovating with its building HVAC systems for years, and it’s not been without its challenges. Two summers ago there were several days when they could not adequately cool the campus, and there was an uproar about it. When I was researching this blog post, I spoke with an engineer who teaches part-time at Cal Poly, where they are also developing a zero-emission on-campus heating system. These projects, which enable those on campus to learn so much and develop many highly relevant skills, are by their nature risky and require extra attention. But that is how we learn, and Foothill is first and foremost a learning institution.

Should Foothill be embracing this opportunity rather than running away from it? Would a more forward-thinking engineering firm provide a different evaluation? Would someone digging into the eye-popping $20M cost differential for the Gayner design find some savings? Are partnerships possible so that Foothill can lead the way rather than follow the leader? And where are all of the faculty and students who should be weighing in on this? They need to speak up. Information about Monday’s board meeting can be found here. Directions for emailing the board can be found here.

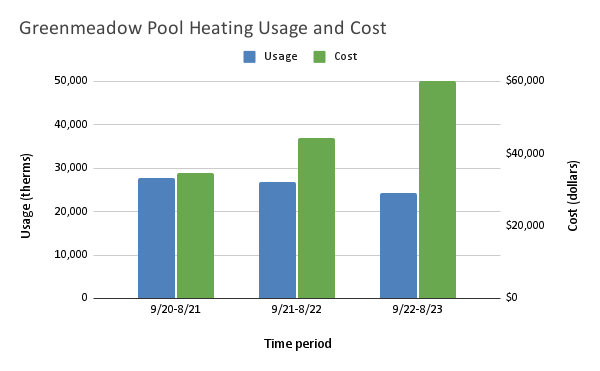

Foothill’s Board of Trustees bears much of the risk for this decision. It is their job to be prudent. But they should keep in mind that choosing gas comes with risk as well. Below is a graph showing the gas use and gas expense for a 25-yard, 8 lane pool in Palo Alto over the last three years. The Greenmeadow Pool’s gas use has decreased by 13% over the past three years, but the gas bill has gone up by 72%.

Any analysis of the cost of choosing gas for the Foothill pool should include not only the time and expense of dismantling and replacing the gas system before 2035, but also paying what are likely to be increasingly costly bills while the gas boilers are in place.

This energy transition is not easy but it has to happen. Decisions like this are where the rubber meets the road. This summer, which broke heat records in much of the country and the world, will be one of the coolest summers of the rest of our lives. The only way to turn that around is to stop burning fossil fuels. Foothill, what is your plan?

Update: The Foothill-DeAnza Board of Trustees met on Monday to discuss this issue. You can find my summary of that meeting here.

Notes and References

1. Berkshire stated during the August board meeting that “In many of our projects, from the city of Folsom, to the city of Albany, to Piedmont, to a lot of these projects, the conversation of electrification has come up with today’s technology. And in every case, with the exception of Mountain View, it’s always been that it’s an issue they cannot afford, both to capitalize and to operate when you look at this.” He must have misspoken about Piedmont.

2. Power outages typically last a few hours. Mamuyac said he would recommend covering the pool if an outage proves to be extended beyond a few hours. Pool pumps require electricity either way, though it is much simpler to provide a power backup for a pool with gas heating than with electric heating since the electric load is much smaller.

3. Pat Showalter, the Vice Mayor of Mountain View, disputes that characterization. “That’s not right, costs were discussed. They told us what each component of the update was going to cost, operating costs too.” Then she added “It is fair to say that, the way we see it, we’ve changed the regulations, and it’s serious business, like building codes. We have to follow the rules.” She continued, saying: “We do consider not going forward with electricity when it’s really out of the question, for one reason or another. For instance, in an upgrade that was done recently to the HVAC of the Performing Arts Center, it just wouldn’t work to use a heat pump. The cost was truly excessive. So we’re going with older technology, but we’re buying offsets to make up the difference. The offsets are local, with projects in Mountain View itself.”

4. Pool covers make a huge difference in energy use, so it surprises me that Foothill has not been using them. As a sometime Masters swimmer, I have done my share of covering and uncovering pools. I would love to see more/better automation around this.

Current Climate Data

Global impacts (July 2023), US impacts (July 2023), CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.