A few months ago our ex-Governor and ex-Terminator Arnold Schwarzenegger penned an op-ed for USA Today urging us to “Move fast and build things. Build a clean and abundant energy future. Build better. Build cleaner. Build now. Build, build, build.” He bemoans the bureaucracy that is delaying the rollout of transmission, carbon capture and storage, renewables, and more.

Similarly, climate writer Robinson Meyer expressed frustration with some of the environmentalist pushback in a conversation with the New York Times’ Ezra Klein. He suggested that instead of environmentalists pushing back on carbon capture and storage (CCS) infrastructure, they should embrace it wholeheartedly. “‘You want to do CCS? We totally agree. Essential. You must put CCS infrastructure on every power plant, on every factory that burns fossil fuels, on everything.’ If progressives were to do that and were to get it into the law … the upshot would be we shut down a ton more stationary sources and a ton more petrochemical refineries.”

But many environmentalists are not encouraging wholesale adoption of this technology. In fact, many are warning against adopting it too quickly, even while acknowledging that it can be useful for hard-to-abate sectors like cement and steel production as well as for the negative emissions we increasingly need as we slow-walk our way to climate mitigation. One of the leading negative emissions companies, ClimeWorks, says that “access to safe and permanent geologic CO2 storage will be a core requirement of achieving the mass-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal needed for net-zero”.

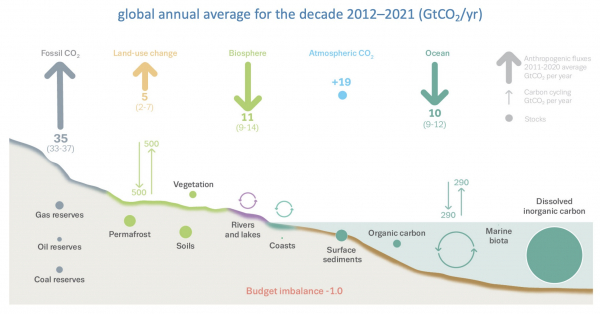

It is difficult to reduce CO2 emissions from cement and steel manufacturing. One option is to capture CO2 at the flue and sequester it underground. However, a sizable well would capture just 1 Mt CO2/year. Other options include green hydrogen fuel and alternative cements. Source: EPA Carbon Capture and Storage Information Session (2022)

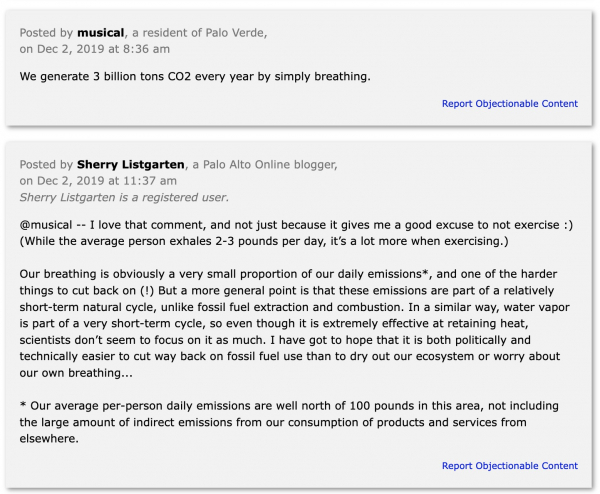

So why don’t we just get moving on this and build, build, build? What are we debating? I’ve written about CCS before, but as a quick summary, carbon dioxide (CO2) is captured from a point source (e.g., a smoke stack) or from the air, compressed to a supercritical fluid, and transported to a sequestration site (typically by pipeline). There it is injected a mile or so below the surface via a “Class VI” injection well, where both physical and geochemical processes can keep it below the surface for hundreds of thousands of years if all goes well.

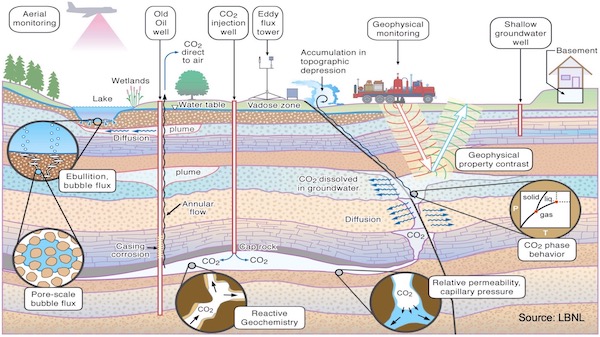

This diagram shows two CO2 injection wells, one into a saline reservoir and one into an old oil field. Some experts believe that old oil fields are the easiest repositories to use since they are well mapped and have low pressure, so can more easily accommodate CO2 injection. The diagram also shows a fault line and a freshwater repository near the surface. Source: EPA Permitting Report to Congress (2022)

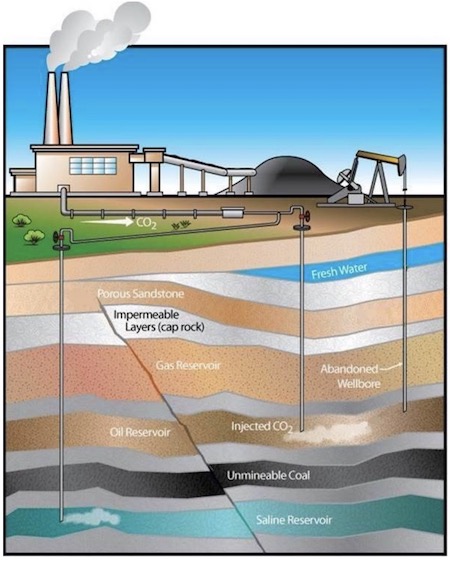

Oil and gas workers have many of the skills needed to design, build, and operate this infrastructure, so their companies and others are jumping on the new CCS incentives offered by the Inflation Reduction Act. In Louisiana alone, there are applications for 39 wells. (And that number seems to go up every week.)

There are many carbon capture projects in development across the US, with a concentration in the Gulf Coast. Source: Clean Air Task Force (2023)

Our Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a permitting process that is meant to ensure that these wells are safely sited, constructed, tested, monitored, and closed. That is important since leaks in the wells and fractures from underground pressure can contaminate drinking water supplies, induce seismicity, and cause CO2 to migrate to the surface where it can linger for hours. The pipelines can also leak, compromise wetlands, or even explode and disrupt nearby communities. The EPA is intent on ensuring that communities already disadvantaged by polluting industries are not further compromised by CCS.

This diagram shows the different types of storage mechanisms, potential leakage pathways (e.g., via old wells and fault lines), and monitoring mechanisms. Source: EPA Inspector Training Course (2019)

The oil and gas majors are confident about the technology, stating that “CCS technologies have been operating safely in the US for more than 50 years with an established record of performance.” They are frustrated with the slow EPA approval process -- the EPA has approved only six applications to date, with just two in operation. One expert told me: “I’ve been told that the EPA has not, cannot and will not be able to process applications for Class VI permits in a timely and competent manner. In that case, it is obvious that States need to step in to enforce the EPA regulations if progress is to be made on carrying out the intent of the IRA legislation.”

Indeed, the EPA has said that it would like to outsource the permitting process to states, as it has done for other types of injection wells. Louisiana is one of several states seeking primacy over permitting Class VI wells. The governor and the developers argue that Louisiana has better knowledge of its local geology, good expertise from the considerable well activity already in place, better access to local communities that may be impacted, and therefore can do this more quickly and more safely. The Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association says that “Local oversight through the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR) will give the state the ability to quickly and safely implement the latest processes, technologies, and regulations to keep Louisiana at the forefront of energy innovation and production.”

Not everyone is in agreement that LDNR would do a good job. Paige Powell’s family grew up in (and in several cases got cancer in) Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. Powell is now Policy Director for Commission Shift, an oil and gas watchdog in Texas. Powell points to inadequate supervision that has led to thousands of old and abandoned wells and an unsafe injection program that has resulted in geologic subsidence and uplift, both in Louisiana and in nearby Texas. “The induced seismic activity, sinkholes, well corrosion and blowouts that we have seen in Texas (Permian Basin, Lake Boehmer, Anita Ranch, The Wink Sinks, Daisetta Sinkhole, Crane County Geyser) are similar to what’s happening in Louisiana (Bayou Corne, Freshwater City), and are indicative of the myriad problems with the Class VI programs managed by these state agencies.” During a hearing on this topic Powell expressed doubts about LDNR, the organization that would take over permitting from the EPA, stating that “LDNR has a long history of not protecting the resources which it stewards.”

Scott Eustis, the Community Science Director for Healthy Gulf, is equally distrustful of LDNR. He says during a hearing: “We have a broken land. Look at a map for the vast non-compliance issues the department has. There are thousands of broken wells across the state. The department does not have the staff to deal with it.” He points to the more than 200,000 wells in Louisiana and the existing geologic fragility and questions how CO2 can safely be stored in that context. “You see two kinds of applicants…. Some take the bore hole guidance by EPA seriously, and they say we have to build a 100-mile pipeline to get to the last bit of Louisiana that is not Swiss cheese. That is a tremendous wetlands impact. That is Conoco, Exxon, and Denbury. Denbury says they have to inject into a federal wetlands restoration project because Louisiana is so unsuitable with respect to the number of bore holes. Then we have companies like Sempra, totally ignoring that, they’re injecting into Black Lake with 1500 existing bore holes, just in that one field.”

The Gulf Coast Pipeline has impacted over a thousand acres of wetlands. Source: Healthy Gulf comment to EPA (2023)

Multiple environmental organizations question Louisiana’s commitment to ensuring the safety of its people and its environment. The Environmental Defense Fund states that “Louisiana has a well-documented history of favoring industry and economic interests over communities and the environment.”, questions the state’s commitment to environmental justice, and dismisses its staffing plan as ”far insufficient to address the large and growing list of proposed projects.” The Clean Air Task Force highlights an active hostility in the state towards environmental justice, with the state having filed a lawsuit against the EPA challenging its relevance. They also point to a conflict of interest in which the inspection and permitting program is funded by operating wells, potentially leading to pressure to approve permits. Earthjustice shares those points and takes issue with the lack of long-term liability for corporations deploying unproven technology. Louisiana is asking the state to assume both legal and financial responsibility from corporations after the well is closed and deemed safe, which deviates from EPA requirements and the practice of the two other states that have primacy (Wyoming and North Dakota). Earthjustice also points to the state’s low fines for violation ($5000/day vs EPA’s $60,000+/day) and reluctance to enforce them. The concerns go on, comprehensively depicting a business-friendly department with lax oversight, inadequate capacity and expertise, and little interest in protecting disadvantaged communities.

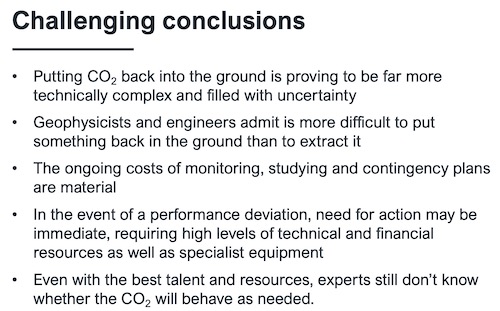

In light of this, what do we make of the fossil fuel companies’ assurance that “CCS technologies have been operating safely in the US for more than 50 years with an established record of performance?” The fact is that there is nothing operating at the pressure, capacity, and scale of the proposed wells, which makes them much more challenging to operate safely. Furthermore, many of the prototypes and even the success stories have had serious issues.

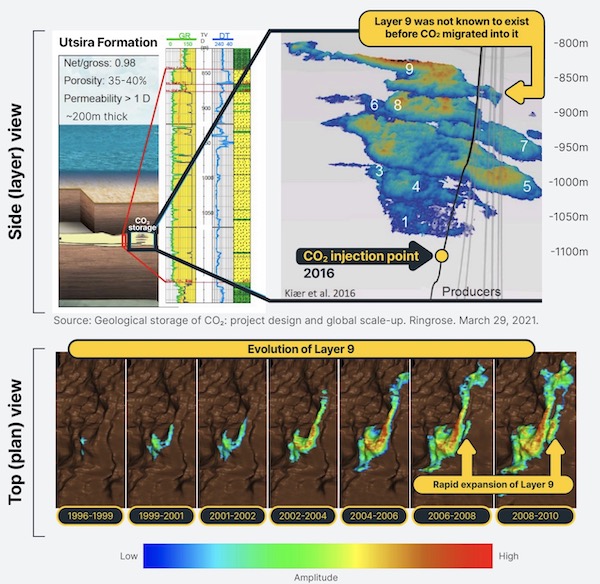

A report released a few months ago details significant issues that some of the most hyped Class VI wells, managed by Equinor in the Norwegian sea, have had. “The two fields were among the most thoroughly studied pieces of earth on the planet. Despite the wealth of information in hand, scientists could not predict the geological challenges.” In one of the projects, the CO2 moved to an unexpected region after only three years. They still do not know the extent of this new region that is being filled.

Carbon dioxide in the Sleipner well moved to an unexpected area after just three years. Source: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis presentation (2023)

In the other, pressure in the reservoir increased dramatically after only 18 months, risking its integrity. The well had to be closed and another one found quickly and at great expense, putting the nearly $7B project in jeopardy. The report draws some blunt conclusions.

Source: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis presentation (2023)

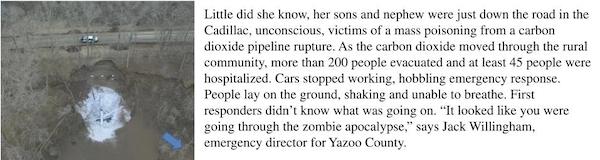

If high pressure CO2 underground leaks and seeps upwards into drinking water reservoirs near the surface, the water becomes acidic and can leach toxic chemicals, endangering our water supply. But what about CO2 leaks into the air? That seems safer, no? Well, think again. In 2012 a CO2 pipeline exploded in Satartia, Mississippi. Below is a photo of the pipe break and a snippet of a report of that event, beginning with a woman who hid under the covers with her young grandchild and great-grandchildren when her son called to warn her about an explosion he heard.

Image source: Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, Text source: National Public Radio report (2023)

This happened even though the pipeline valves were shut off within minutes of the accident. This technology is still very new, particularly at the pressures and scales now being proposed. And it’s not only environmentalists pointing that out. Almost every major power organization in the United States is calling out the immaturity of the carbon capture and storage industry as they push back against the proposed Clean Air Act, which relies on CCS to clean up power plants. They say that relying on it so soon is infeasible and will put our power grid at risk.

When companies rush to deploy risky technology, who is most likely to bear that risk? These projects are historically located in the communities least able to fight back. With that in mind, Louisiana passed a bill last month stating that 30% of revenues from CO2 storage under state land or water bottoms would go to local governments. But is that what residents want? Many are enthused about the jobs and revenue this will bring to their community, and have considerable trust and confidence in LDNR and the developers. Others worry that a decrease in oil and gas revenue would threaten the finances of local schools, and feel they need to support the industry to protect their kids.

But those who have felt more of the negative impacts from oil and gas development are strongly opposed to more development that puts them and their communities at risk. The split at the hearings is stark. Louisiana resident Jesse George spoke with a quiet anger at a hearing on this topic. “There is a groundswell of folks in Louisiana who are prepared to challenge every page of permit and oppose every foot of pipeline to prevent further degradation by the same petrochemical companies that have turned our state into an ever-eroding cesspool…. We know from past experience with oil and gas wells and pipelines where these projects will be sited -- in low-income communities, Black communities, and Indigenous communities. And I can guarantee you that none of the folks speaking in support today are volunteering their own neighborhoods for the siting of these projects. Environmental justice must be more than campaign rhetoric and public hearings such as this must be more than just a procedural box to check.”

An Earthjustice spokesperson told me “Our take is that the ‘move fast and break things’ model has gotten us to the point where the burdens of our society are borne by the most vulnerable people, and that is not a sustainable model for a true transition. We would very much like to move fast while considering safety and equity. We must learn lessons from the fossil fuel economy and not make the same mistakes building something new.” That sentiment is similar to what a geologist expert and CCS consultant told me last year, though he looks at it more from an economic perspective. “Permitting and regulation is critical… If we don’t do it right, it will be like fracking. Everybody hates fracking. We don’t want that to happen with CO2 storage.”

As we work carefully to develop successful deployments, we should be ensuring that this limited resource, CCS, is used for the projects that need it most, and not to unnecessarily expand fossil fuel use. Earthjustice worries about this, saying: “A major, major issue for us is not whether we should be investing in negative emissions (we should be) through CCS, but what CCS in practice will be used for. Many CCS-related projects would expand and accelerate petrochemical buildout and are part of a dangerous growing global push toward carbon capture and away from phasing out fossil fuels.” CCS should not provide an excuse to reduce the pressure to ramp down fossil fuel use in the power sector, agriculture, and more.

The generous new federal incentives for emerging technologies can lead to unhealthy and ultimately counter-productive gold rushes with perverse outcomes. There is a lot of concern that this will happen with both CCS and hydrogen incentives. The pushback we are seeing is critical to ensuring that our emissions goals remain front and center so that these incentives achieve their purpose, which is not to enrich oil and gas companies or accelerate our use of fossil fuels.

I’d love to hear your take on some of the permitting debates, and if you have experience living in a community with an environmental burden.

Current Climate Data (June/July 2023)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

A total of 15 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters have been confirmed in the United States this year—the most events since 1980 for the January-July period. These consisted of 13 severe storm events, one winter storm and one flooding event.

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.