Last week I went hiking in Glacier National Park. It was absolutely beautiful, the meadows filled with flowers, and lakes, streams, and waterfalls brimming with clear cool water.

Lush meadows were filled with flowers in mid-July in Glacier National Park.

Flowers were buzzing with insects, and butterflies were everywhere. It reminded me of what a vibrant garden should be. This robust lower layer of the ecosystem supported many birds, from a ptarmigan mother with her babies in the subalpine to a golden eagle flying high over meadows. At one stop an ornithologist in our group observed 25 different bird species. There were many larger animals as well. We saw three mule deer, two vigorous bull moose, two cinnamon-colored bears, and one very healthy looking mountain goat, along with signs of the local sheep population. The park was resplendent.

Bees, butterflies, and other insects (here a grasshopper) were all over the plants in the park.

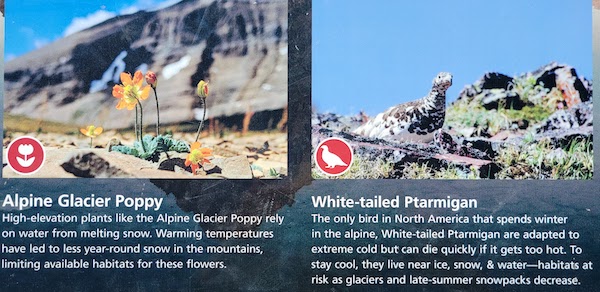

There were also indications that the park’s ecosystem is changing. The glaciers are disappearing as the climate warms. While the park hasn’t updated its 2015 estimate of 26 glaciers, down from over 100 in the 1800’s, our guide said he believes only 16 or so remain. In the Two Medicine area, there are no longer any glaciers. As a result, the lakes are green rather than turquoise (the light entering the water no longer reflects off of ground-up glacial “flour”), and the animals have less access to year-round water. The park service calls attention to a variety of impacts from the warming climate, as shown in the signs below.

Signs in Glacier National Park reflect the impact of the changing climate on the park’s ecosystems.

The park has also been warm this year. The week I visited was the hottest stretch of July in memory, with six straight days of 90+ temperatures. Our guide said that in May the temperature hit 80 degrees, unheard of in an area where 40-50 is more normal at that time of year. The snow melted early, the bloom is early, and he worries about what that means for late summer and fall.

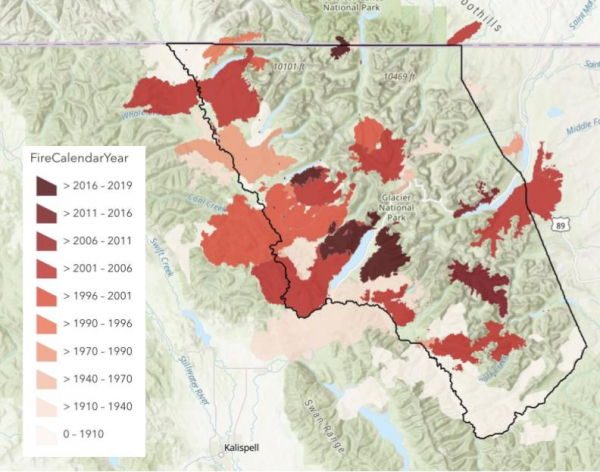

Signs of fire are everywhere throughout the park, which has seen fire almost every year but with more acreage affected in recent years.

Source: Glacier National Park Wildlands Fire Map

Among the signs we saw were uniform stands of young trees growing back in fire-scarred areas. The lodgepole pine grows back quickly after fire, though over time the trees will be killed by the mountain pine beetle, making room for other species to grow.

A uniform stand of young lodgepole pines has grown after a fire.

Even though our area has been relatively cool and wet, fire and heat have been a topic of conversation here as well. Have you been on a video call recently where participants talked about heat or smoke where they are living? Were you on an unusually hot vacation recently?

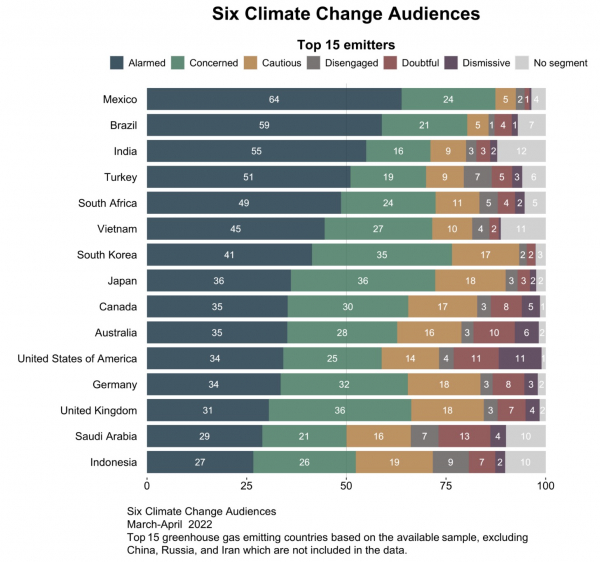

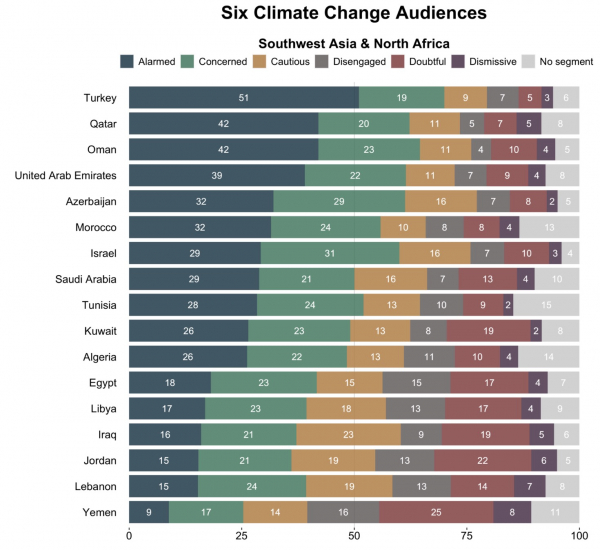

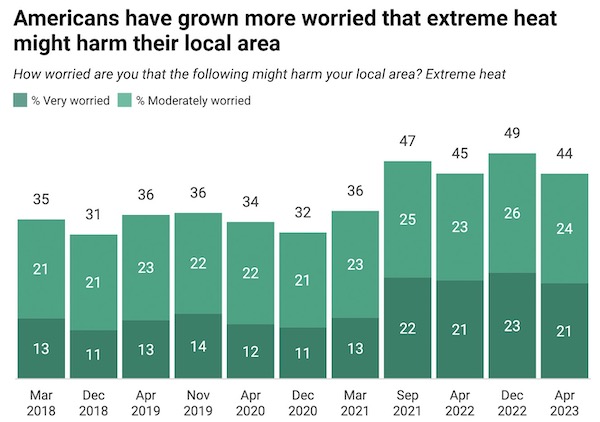

Yale Climate Communications reports that people are increasingly worried about extreme heat. If you consider that not only is this one of the hottest July’s in history, it is also likely to be one of the coolest July’s of the rest of our lives, that concern is understandable.

This survey was done before this summer’s heat. Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

And this brings me to an anecdote from the trip, one that has nothing to do with climate change on one level, but everything to do with it on another.

Our guide in the park was a dog lover, the happy owner of a rescue mutt from a nearby Indian reservation. Yet he agreed with park policy forbidding dogs on park trails, explaining among other things that their waste contains bacteria that can be toxic to native wildlife. While we saw dogs in campgrounds and on roads, we did not see them on Glacier trails, at least until the last day. About two miles from the trailhead, a couple were walking up the trail in mid-afternoon with two large dogs.

Glacier National Park allows only one company to guide in the park, and the guides are well trained. They are aware that they have a responsibility to maintain the park, especially given that staffing in the park is thin. And yet our guide said nothing. At the end of the hike, I asked him why not, and he replied “Oh, I didn’t want to be ‘that guy’”. And that got me thinking, because I see this kind of avoidance as well when it comes to climate change. People might be reluctant to challenge climate misinformation, or to explain that they are getting a heat pump not only for the air conditioning but also to reduce their carbon footprint, or to acknowledge in a restaurant why they are choosing the vegetarian option.

I certainly understand the reluctance to say something. It’s easier to keep your head down and be quiet. Sometimes it’s even the best thing to do. On the other hand, it is the job of a park guide to educate people and to protect the park. And in my opinion, it is our job to find ways to talk productively about climate change. Positive conversations can improve our understanding, make it seem less daunting, encourage action, and build bonds. Yet we still aren’t talking enough about it.

What say you? With so many more people worrying about the impacts we are seeing, have you been able to push aside your concerns about virtue signalling or moral policing to reflect in an empathetic way on what you are seeing and some changes you are making? Or is it still proving too difficult? I’d love to hear about any productive conversations you have had during this hot summer.

Notes and References

1. For those who are curious, I did buy offsets for the round-trip flight between SFO and Kalispell. Offsets don’t make up for the emissions, but it is a positive step that I can take and I enjoy the process. Here is what that looked like.

My airline and FlightAware both told me that the plane I used was a CRJ-700. I looked up the flight on atmosfair and found that the round-trip released 665 kg of CO2. An estimate from myclimate was 522 kg and from carbonfootprint was a much smaller 380 kg.

I then went to ClimeWorks, which will sequester an amount of emissions for you, as close to negating the impact of those emissions as it gets, but found the cost to be $900 for 665 kg, more than the cost of the flight itself. So I visited the much(!) cheaper Gold Standard offset marketplace, which offers good quality (e.g., permanent, additional) offsets. Rounding up to 1 ton, I found a project that resonated after my visit (planting biodiverse forests in Panama). I purchased the offsets and they sent me a certificate indicating that 1 ton worth of offsets had been retired.

Current Climate Data (June 2023)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.