I just finished reading an Environmental History of Lake Tahoe by David C. Antonucci. Tahoe has faced an evolving set of environmental challenges over the years, from resource extraction to development to climate change. How did we deal with these issues in the past, what were the consequences of our actions, and what is in store for the future, at one of the most spectacular places in the country?

Lake Tahoe in winter

Logging

In a short forty years in the late 1800s, we clear cut nearly all of the old-growth trees in the Tahoe Basin. Prior to the Gold Rush, Tahoe’s forests were filled with 200-300 year old trees about 3-5 feet in diameter. The forests were shady with minimal understory -- they say you could drive a wagon through them easily. Occasional fires formed groves and kept smaller growth under control.

An old-growth tree still standing in Tahoe City

But in the 1860’s two events conspired to drive demand for the wood in those trees. One was the discovery of silver and gold in Virginia City, Nevada. A massive amount of wood was needed for mine construction, for building homes and businesses in the area, and for fuel for heating. The east slope of the Carson range was quickly cleared and lumber companies had to move into the Tahoe Basin despite the difficulty of extracting wood. Special railways were built to haul wood from the edge of the lake up 1000 feet to the Basin’s rim, where it could then be floated down for miles in specially designed flumes to the railroad in Nevada.

Cut logs were floated in booms over Lake Tahoe to Glenwood, where a railway took them up and over the Carson range to Nevada. Source: Western Nevada Historic Photo Collection, contributed by Stephen Gennerich

At the same time, the Central Pacific Railroad was being extended from Sacramento into Truckee. The snow sheds and railway ties demanded a lot of wood. Lumber was floated down the Truckee river from Lake Tahoe to where it was needed.

By the end of the 1800s, two-thirds of Tahoe’s forest was clear-cut, with the rest vanishing in the early 1900’s. The loss of forested habitat led to the disappearance of grizzlies, wolverines, red foxes, wolves, and bighorn sheep from the Sierras. It also changed the nature of the forests themselves. White fir that thrived in the sunny environment post-logging is now dying off because it is vulnerable to drought. These dead trees combined with overly dense second-growth forest has created a tinderbox out of the Tahoe forests that poses a significant threat to the area today.

The reddish tops of dying trees weakened from drought and insects can be seen all around the lake basin. Here they are visible in Tahoe City.

National Park Status

The decimation of the forests did not go unnoticed at the time. Several attempts were made in the late 1800s and early 1900s to turn Tahoe into a National Park, but none succeeded. From what I read, several factors were responsible for the failures: a reluctance to use government funds to pay for the ravaged land, since that would reward the very people who had caused the damage; resentment among Tahoe locals that San Franciscan “elites” were proposing to restrict their livelihoods and freedoms; and, towards the end, a concern that the area was already too exploited and developed for tourism.

The conservation efforts were not entirely futile. In 1899 much of the area was designated a “Forest Reserve” and in 1907 it was converted to National Forest. Government began to purchase the damaged land, 85% of which was privately held. Today public agencies own 88% of the land, and 78% of all land in the basin is National Forest. This protection gave the forests a chance to recover.

Water Troubles

Water is a constant source of contention in California, and Tahoe has been no different. The lake was first dammed in 1870 (by Leland Stanford’s company) to help send logs down the Truckee River. Lake water was used to power sawmills, to clean out waste, and to fill log flumes. Dry Nevada eyed the lake’s water for agriculture and in 1905 built the Derby Dam downstream on the Truckee to divert water from Pyramid Lake to Lahontan Valley farms. The level of Pyramid Lake dropped 84 feet, and nearby Lake Winnemucca dried up entirely.

More demand for Tahoe water emerged. The Tahoe dam was upgraded in 1913 to provide electricity, and arguments ensued about the appropriate lake level, with lakefront owners concerned about their property, environmentalists concerned about erosion and loss of spawning habitat, and water users concerned about access to their supply.

Postcard of the Tahoe dam circa 1919. Source: Western Nevada Historic Photo Collection, contributed by Linda Henris

Development impacted water quality, with lumber mills dumping sawdust and homes and businesses dumping sewage. This combined with over-fishing caused the native fish population to plummet. People tried to correct this by adding new species of trout, along with crayfish and then Mysis shrimp to provide food for the new species. But the native Lahontan cutthroat trout disappeared and the shrimp are now outcompeting the local zooplankton (Daphnia) that help to keep the lake clear.

Today the lake continues to struggle with the impact of the intentionally introduced non-natives as well as a number of other invasive species. Many demands remain on Tahoe’s water: agriculture, recreation, fish and wildlife, municipal water supply and hydroelectric generation. The lake level is carefully regulated and a watermaster controls the outflows and who gets what.

Cars and Year-Round Tourism

Through the 1940s, relatively few people came to Tahoe. There were only about 3000 residents and visitation was seasonal. Tourists tended to use trains and ships, and they stayed together in resorts so their impact was relatively low. A special train, called the Snowball Special, ran a (long) day trip from Oakland to Sugar Bowl. Travelers with more time would take a train into Truckee and then a smaller train into Tahoe City where they would either stay at a resort or take a ship to another part of the lake. Once at the lake, they would generally stay in one place and use nearby services.

Passengers on the Lake Tahoe Railway from Truckee to Tahoe City could walk from the pier to their inn or hop on the SS Tahoe to go elsewhere along the lake. Source: Western Nevada Historic Photo Collection, contributed by Stephen Gennerich

That all changed as cars got more popular. By 1935 all roads in the basin were paved to facilitate car travel. In 1941 the little railroad from Truckee to Tahoe City was dismantled and sold for scrap. 1947 saw the first paved two-lane roads into the basin, and i80 was extended to Truckee in time for the 1960 Olympics at Squaw Valley.

Businesses, resorts, and parking lots spread out around the lake to attract the new drivers. Sugar Bowl opened in 1939, Palisades in 1949, and Heavenly in 1956. With the Olympics on TV, Tahoe became a ski destination, and Alpine and Mt Rose followed in the 1960s and Northstar and Kirkwood in 1972. At the same time casinos proliferated, creating more opportunity for year-round recreation. Harveys and Harrah’s opened in 1957, and a few others in the next two decades.

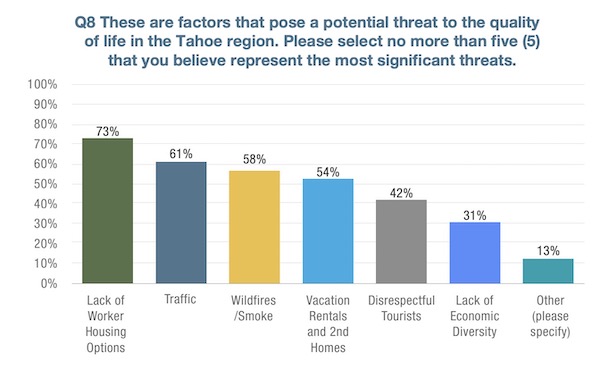

With a dwindling reliance on transit and increasing numbers of visitors, traffic quickly grew bad and has only gotten worse for both visitors and locals. Residents cite traffic as one of their top concerns.

Traffic is a top issue for Tahoe residents. Source: Tahoe Prosperity Center’s 2022 Community Report

Development, Lawsuits, and More Lawsuits

Along with year-round activity and cars came demand for housing. A 1964 plan for the region called for a population of 313,000 by 1980, with three roads ringing the lake and a bridge over Emerald Bay. Developers went all-out building condominiums. 1500 homes were built in the Tahoe Keys in the 60s, 6500 homes in Tahoe Donner in 1971, 9000 units in Incline Village in the 70s, and so on. The local housing stock went from 7000 units in 1960 to 46,000 units in 2010. More casinos and ski areas were approved.

But this development brought environmental harm. There were multiple sewage leaks into the lake, and erosion and sediment from construction and traffic started to cloud the water. Lake clarity fell from 102.4 feet in 1968 to just 67.4 feet in 2000. Scientists began to study the health of the lake in earnest, and concerned residents pushed back on aggressive plans. In a particularly egregious example, South Lake’s Tahoe Keys development destroyed a big part of the Upper Truckee Marsh, an important inlet to the lake that filters water and provides critical habitat. The warm waters of the Keys lagoon soon became home to invasive fish, mollusks, and aquatic plants.

The Tahoe Keys development was built on top of sensitive marshland at the southern edge of the lake and created a shallow warm lagoon that provides habitat for invasive species. Source: Google Maps

California began putting restrictions on development, but Nevada had little interest in such constraints. While the states bickered, developers angry with California sued to begin projects. Local governments sued over local control. Property owners sued over property rights. Unhappy residents started blaming lake scientists for exaggerating the harms -- the forest was recovering from logging and the lake would recover too, it was all part of a natural cycle. As livelihoods were threatened by regulation, public meetings got tense, requiring armed guards. Some developers started bypassing the permitting process altogether.

It took years and a concerted effort to build consensus across state and local governments, tribal governments, environmental organizations, property rights advocates, scientists, and federal agencies. Over time they settled on a plan that would cap development in the basin, permit square footage dependent on environmental sensitivity, and allow landowners to trade development rights. At the same time, the federal government got funding to buy up property with low development potential. Temperatures cooled and people rallied around a new plan issued in 1987 by the new Tahoe Regional Planning Association. Today several organizations work to balance economic growth with sustainability, with an emphasis on restoring sensitive habitat while building up in town centers and encouraging mass transit.

But it is an uneasy truce between developers, residents, and environmentalists. Much of the housing stock sits empty as second homes, and prices have become unaffordable for locals. Restoration is slowly happening and transit is getting some traction, but the money for those comes from new development, causing some to worry that the planning organizations have an inherent conflict of interest. Development proposals are popping up around the lake. Tiny Tahoe City (population 2,700), has plans for two large hotel and condominium complexes along with a 150-unit affordable housing development. Placer County continues to adjust its Area Plan to encourage responsible redevelopment and economic growth.

A large hotel-condo complex proposed for lake’s edge in Tahoe City. Source: Boatworks

Going Forward

We see from Tahoe’s history that it is difficult to restore a damaged ecosystem, whether it is a forest or a lake, and we learn that our tinkering can cause more harm than good. We see that business interests are powerful, and balancing their interests with those of residents and the environment is difficult. We learn that government intervention can help, whether it is providing funds to protect and restore or crafting regulations to prevent damage. But money is limited, space is constrained, and regulation can chafe. We find that we are not as smart as we think, and nature is not as resilient as we would hope. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, but that ounce is easily dismissed.

I wish I were more optimistic about the future of Lake Tahoe, but we are asking a lot of the residents and policy makers. It is not easy to live in a place that so many want to visit. It is even harder to protect such a place, which takes time, knowledge, foresight, and effort. And it is nearly impossible to succeed when multiple governments are involved and vested interests with deep pockets are pushing for advantage. Even when everyone agrees that they care about the lake, there are degrees of caring and history shows us that the degrees with the most money involved will prevail.

Will we change the course of Tahoe's history and find a way to both protect and enjoy the area? Or will we love it to death? I’d love to hear your encouraging thoughts in the comments!

Notes and References

1. An initial version of this post included information about the impact of climate change at Tahoe in a section at the end. But it made this post too long and unwieldy, plus that topic deserves its own post, so I removed those paragraphs. If you are interested, this State of the Lake Report released in July 2022 is a great place to start.

2. A set of threshold metrics, evaluated every four years, is used to evaluate the environmental health of the Tahoe Basin. The next report will focus most on air quality, fisheries, soil conservation, vegetation preservation, water quality, and wildlife, with more attention to biodiversity, as described here.

3. Interesting fact: The daily evaporation from Lake Tahoe (half a billion gallons) would meet the daily water needs of 5 million Americans. Source: Tahoe Environmental Research Center’s State of the Lake Report 2022

Current Climate Data (January 2023)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.