One afternoon when I was about nine years old, I was standing in the front yard with my younger brother trying to blow bubbles. We didn’t have any store-bought bubble mix, so we held a large drinking glass with a solution that I’d made from a recipe of dish soap, water, and a little sugar. We were using drinking straws to blow the bubbles, with little success.

A neighbor from down the street, a girl of about my age, came along and asked what we were doing. I explained that we were trying to blow bubbles with some homemade bubble mix. She said it looked like we were drinking it, and for some reason I decided to convince her that it didn’t taste all that bad since it had sugar in it. She didn’t believe me, so I insisted that it tasted pretty good and pretended to drink a little while shooting my brother a look to keep him quiet. I handed Hannah a straw.

To my enduring surprise and dismay, Hannah didn’t just taste the bubble mix, she took a big swig through the straw, turned a sickly shade of green, and eventually threw up on the lawn. I ran inside to get help and got in a huge amount of trouble. Consequences ensued.

During my hours and days of home lockdown, I theorized about different variations of that encounter, and in particular one in which someone leaves a bottle of bubble mix (or poison) in a public park. Who is to blame if a passerby picks it up and drinks from it? I eventually concluded that (a) the bottle would need to be pretty well sealed, so only a purposeful adult could open it; and (b) the bottle would need to be clearly marked with a graphic skull and cross bones. If both were true, then was the bottle depositor still at fault if someone drank it and got sick? And would it matter if the bottle were left in a public park vs somewhere else? Or if the passerby got really sick vs just a stomach ache?

Those dilemmas came back to me this week when I was thinking about the responsibility of oil and gas companies for their past and on-going role in climate change. When there is evidence that they suppressed or downplayed the science of climate change in order to grow their business, the case against them seems pretty clear. But if they did not engage in misinformation or disinformation, and instead just provided their product to those who were asking for it, should they still be held liable? And does it matter if that is a backwards-looking excuse or a forward-looking rationale?

Last month the CFO of Chevron, Pierre Breber, was interviewed for the Dean’s Speakers Series at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. Breber explained that Chevron is continuing to invest in its traditional oil and gas business while also investing in clean technologies. “We’re going to have a traditional business that is going to be very low carbon (1), but it’s going to meet the demand that society has, which we don’t know what that’s going to be. Then we’re going to have a faster growing new energy business. And we don’t think we have to make a choice of one or the other, we think we can do both. And then depending on the pace of the energy transition, the speed of the two and the size of the two may vary.”

The way he describes it, Chevron is a passive participant in the market, one that simply responds to customer demand and investor interest. (2)

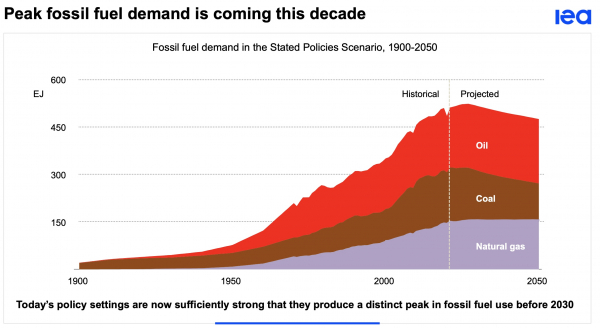

The dean and several of the students challenged him on that stance. Reports from the IPCC and the International Energy Agency (IEA) say that fossil-fuel investment needs to drop quickly in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and reach net-zero by 2050. Breber’s response was to repeat that Chevron is simply meeting demand: “Demand for our products is growing, not shrinking. And that’s in part because it’s 7.5 billion people, we’re going to 9 billion people. Hundreds of millions of people, hopefully billions, are going to come out of poverty, go to a higher standard of living, get something closer to the standard of living that we have, and that takes energy.” (3)

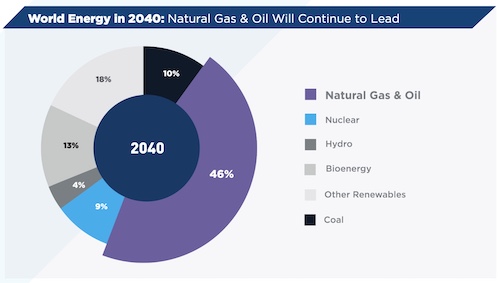

He encouraged everyone to read over the American Petroleum Institute’s Climate Action Framework, which holds that even in 2040 almost half of our energy will come from oil and gas. (4)

Source: American Petroleum Institute’s Climate Action Framework

Students continued to push back, insisting on a better future for themselves and their children. One made the point that we are acting very late to address climate change and suggested that Chevron and the American Petroleum Institute and other fossil fuel companies hold some responsibility for that due to decades-long campaigns of delay and denial. Oil and gas companies should therefore take more responsibility for getting us out of this mess. Breber again asserted Chevron’s passive role: “I don’t accept your premise that we are causing this. We are providing the energy that’s needed today. We will provide the energy that is needed tomorrow.”

Chevron is using that same defense in a lawsuit in Hawaii, denying financial responsibility for the climate effects that locals are experiencing. Chevron argues that everyone has known about climate change for decades and they are not responsible for the choices that people are making. “Members of the public -- including media and government officials -- had ample data with which to make informed policy and personal decisions.”

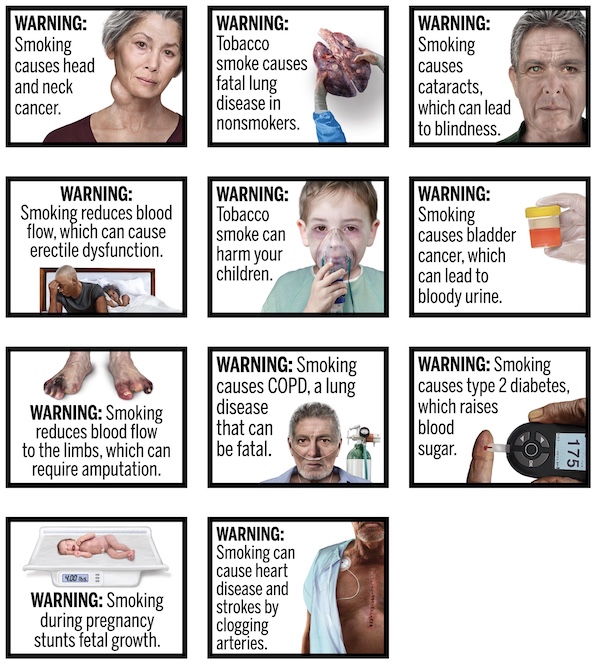

So does that mean it’s okay to put a bottle of poison on a public park bench as long as it’s clearly marked? “Quenches your thirst but makes you sick -- you decide!” It never occurred to my younger self to consider the case where a company was distributing these bottles to hundreds of parks and making a profit off of them. And yet we have cigarettes. We continue to allow companies to produce and sell cigarettes despite their adverse health impacts. Over time we have required warning labels on packages, and in 2023 we may have the more graphic warnings depicted below. But the tobacco companies themselves have shown little interest in weaning people off of their products and we do not insist that they do so.

Source: FDA

Chevron is aware of the harm (and the good) that results from consumption of its products and dismisses any suggestion that it should be responsible for moving the energy market away from fossil fuels. One student who worked as a consultant for oil and gas companies said he was surprised and frustrated by their low uptake of clean technology. He asked what specifically Chevron is doing to accelerate their customers’ switch to clean energy, given that the world needs to be doing that and Chevron has considerable leverage. Breber’s frothy response was unconvincing: “Everybody is working on this. Last year, right around this time, we did a full energy transition spotlight. We only talked about our energy transition strategy. So it’s something that is really essential to winning back investors…. It’s going to take a lot of talent, a lot of companies, a lot of solutions. If it was easy, it would have been done.”

The student’s question stuck with me. Given where we stand now, and everything that we know about how we got here and what the future might hold, shouldn’t the oil and gas companies be using their position and their leverage to accelerate the transition rather than spending their time and money to litigate their right to not care? Breber talked about the need “to balance our fiduciary responsibility to our shareholders who are … teachers and firefighters and folks saving for retirement.” But what about the lives of the children and grandchildren of those teachers and firefighters?

It seems craven for oil and gas companies like Chevron to subjugate their moral compass to the machinations of the markets. But that is too often how America works. The dollar determines our code of conduct and when we fail to price the externalities appropriately we end up with unhealthy levels of trade. We have delayed for nearly two years now an update to the social cost of carbon, which by all accounts should be two or even three times higher than it is today. Will such a change, should it happen, be enough to accelerate investment and encourage real leadership from the likes of Chevron? Or will we just be dragged into court yet again?

What do you think of Chevron’s take on its role and responsibilities in the transition to clean energy?

Notes and References

1. By “very low carbon”, Breber is referring to Chevron’s goal to reduce the carbon intensity of their fossil energy by 35% from 2016 levels by 2028. It may be more accurate to think of that as “relatively low” rather than “very low”.

2. Breber explained that they are pursuing the clean energy path because their customers are demanding it for their own net-zero goals, and investors are looking for ESG options.

3. He observed that many sectors are hard to electrify, which he said means continued demand for oil and gas. When a student pointed out that clean hydrogen can work for many of those sectors, he replied “You’re right, hydrogen can work for a lot of these heavy-duty sectors, that’s why we’re in it, but there’s only so much wind and solar.”

4. The American Petroleum Institute’s graphic is based on a 2018 IEA report that has us achieving net-zero in 2070. As the science of global warming and its impacts has progressed in the last few years, the IEA has come out with a newer report urging a “critical but formidable” roadmap to net-zero by 2050. In that roadmap, fossil fuels drop to just 35% of our energy in 2040 and 22% by 2050.

Current Climate Data (September 2022)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.