With the growing demand for renewable energy, domestic mineral supplies, new long-distance transmission lines, and subterranean repositories for captured CO2 and nuclear waste, I’ve been thinking a lot about land use. Which policies will best help us accelerate the energy transition while protecting our natural spaces? It’s pretty clear that Democrats and Republicans do not agree on the answer, but we have to keep trying to find common ground. No one benefits from the policy reversals we are enduring. Rural communities suffer from volatile revenue, developers struggle to fund projects, and environmental advocates work twice as hard to protect critical habitats from harm.

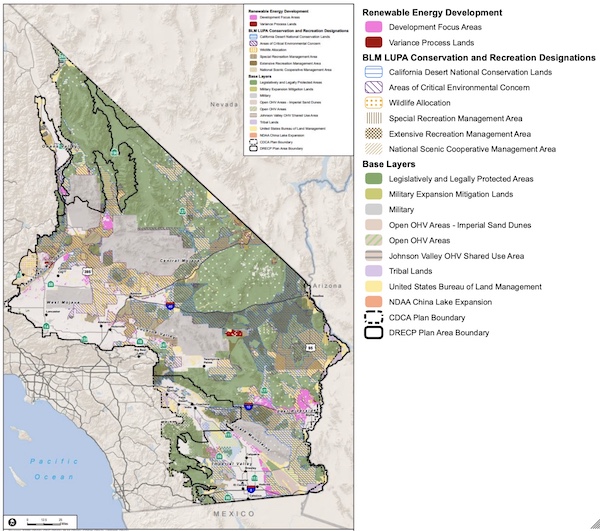

Consider the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, which covers 10+ million acres in the Mojave Desert region of southern California. The goal of the 2016 plan was to facilitate development of renewable energy and transmission in the desert while at the same time conserving desert resources for wildlife, recreation, and cultural uses. As Sally Jewell, the Secretary of the Interior who sponsored this work, describes it: “How do we drive development to those areas that are most disturbed, most conducive to transmission, that aren’t in critical habitat, that aren’t going to bother people? … What (our plan) does for business is, we say if you go to these areas, we’ve done the Environmental Impact Statement, we’ve pre-cleared it for renewable energy, you’re close to power, and we will have your permit in a much more expedited period of time, like 90 days. That’s sort of unheard of, but it’s because we do all of the clearing of the conflict in advance.” The map below shows the “Development Focus Areas” in pink.

Almost 400,000 acres in Southern California, shown in pink, have been designated for expedited approvals of renewable energy and transmission projects. Source: Executive Summary of the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (Figure 2), 2016.

And yet just a few years later, the Trump administration proposed undoing much of this work.

Michael Freeman, Senior Attorney at Earthjustice specializing in energy and public lands in the West, has been dealing with similar issues involving the 2015 strategy to protect the Greater Sage Grouse in the Rocky Mountain region. A multi-year planning effort by the Department of the Interior brought together conservation groups, ranchers, oil and gas companies, local Indian tribes, and area residents. This beautiful three-minute video conveys the messaging that brought these groups together. There is a love for the land, a sense of heritage, diverse uses that require a thriving landscape, and developers who want to avoid an “endangered species” listing that would impose strict constraints. The resulting plans were hailed as a practical way to allow carefully placed development while greatly reducing negative impacts on the environment and preserving the land for multiple uses.

The ability of the sage grouse to thrive (chicks are shown here) is considered to be a proxy for the health of the sagebrush landscape more generally, which is home to many animals. Source: US Department of Interior video

The gist of the plan is that developers avoid the most sensitive and critical habitat areas; prioritize development outside of designated habitat areas; and then mitigate any impacts by conserving and restoring habitat. Freeman says that this “avoid; minimize; mitigate” hierarchy is widely accepted, and the plan more generally was grounded in substantial science.

Unfortunately, just a few years later, more than one million acres of prime sage grouse habitat had been leased to oil and gas companies. The Trump administration had moved to re-interpret the plan to eliminate many constraints on development, and some states welcomed the developers back with open arms. Freeman and Earthjustice were forced to sue the administration to remind them of their commitment, void the new guidance, and block the fossil leases. They won the fight, though an appeal is still active.

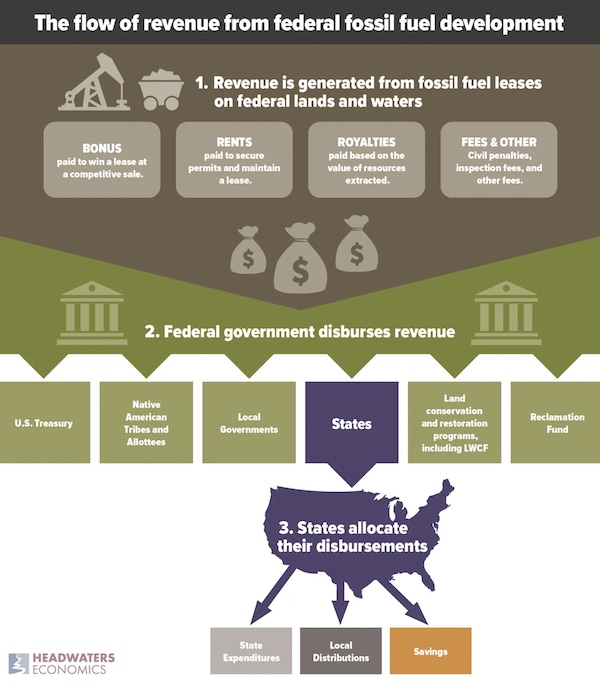

I asked Freeman how this reversal could happen, given the deliberate, comprehensive, inclusive process that went into the planning. He mentioned a few things. “One lesson I take away is that these plans have to have teeth, not just incentives. Leaving too much to case-by-case discretionary decisions inevitably ends up harming conservation goals. The oil and gas companies will always push hard to develop wherever they want to, so there must be clear rules about where they can and cannot go.” I asked why the states didn't push back, and Freeman laughed. “Some of these state governments have their own financial stake in drilling on federal lands. They get a share of the royalties from leasing and development, and it can be a significant part of their state budget. That is especially the case for Wyoming (1), but it is also true to some extent for North Dakota, New Mexico, Utah, Montana, and Colorado. It is no coincidence that some state governments have difficulty pushing back on the fossil fuel industry to protect the public interest, because they rely financially on drilling on public lands.”

In 2020, the large majority (80%) of federal oil and gas payments to states went to state expenditures. The use of this money for day-to-day operations increases a state’s dependency on this revenue. Source: Headwaters Economics

Policies handcuffing communities to fossil energy are very problematic. Mark Haggerty, a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, has spent much of his career studying the impacts on rural communities of levies on their natural resources. He argues that not only does fossil dependence slow our transition to a more sustainable economy, the communities themselves suffer as their resources become depleted or less desirable. And the longer they have leaned into this revenue, the more difficult it is for them to diversify.

For example, some of these regions have imposed restrictions on how much revenue they can raise from other sources (e.g., taxes). Haggerty writes: “Wyoming’s tax structure has become so specialized around fossil fuel revenue that any new jobs created in Wyoming outside the energy industry (jobs in recreation, technology, or health care, for example) fail to generate revenue sufficient to cover the costs of roads, public safety, or water infrastructure required by new growth. This means any new non-energy job is a net drain on government finances.” Politicians have enjoyed cutting taxes when revenue is flowing in, but that income proves hard to claw back in tougher times. Haggerty shares another example from North Dakota: “When oil prices and revenue were high, the state cut its income tax -- twice -- exacerbating dependence on oil revenue by narrowing and specializing its tax base around oil. As a result, the state’s oil and gas taxes currently comprise about a third of the state’s operating budget.”

Somewhat paradoxically, incentives for renewable development can also make it harder for fossil-dependent economies to diversify. The incentives effectively reduce the local revenue from those projects, making them less attractive to the host communities. Haggerty shares an example from Colorado: “Replacing a coal-fired power plant in Montrose County, Colorado, with a similar-sized solar project (100 MW each) would return only a third of the tax revenue to local government because the state lowers the taxable value of renewable energy projects as an incentive to developers.” He adds a case from Montana as well: “Montana’s renewable energy incentive would result in local governments receiving nine times less revenue from a transmission line carrying wind and solar compared to an equivalent line carrying power from coal or natural gas.”

Haggerty believes that we can and must do better if we are to transition to a clean energy economy. “Rural leaders are not uninformed or ideological. Their actions are rational responses to incentives: local governments need revenue to provide services that citizens demand, and local leaders pursue strategies to meet their budget obligations. As long as policies impose barriers to economic diversification, rural communities will struggle to embrace conservation, climate policy, and renewable energy.”

He sees some hope on the horizon, pointing to New Mexico’s Land Grant Permanent Fund and Montana’s Hard Rock Mining Act as models that help communities derive more reliable, diversified, sustainable, and long-term value from their natural resources. On the federal level, he highlights Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, a long-term endowment from which they use primarily the interest, as a much better way to manage revenues from energy investments. The endowment structure reduces income volatility and ensures a revenue stream long after the source of funding has gone.

Earthjustice’s Freeman, who lives in Colorado and works across the Mountain West, is in favor of a new approach to valuing our federal lands, one that creates less dependency on continued fossil development. He explains: “The policy reversals around the sage grouse plans and similar efforts are a huge problem. It hasn’t always been like this. In the 70’s and 80’s, conservation had bipartisan support, and there was much more agreement on the need for strong environmental protections. What I’d like to see -- maybe it’s a pipedream, I don’t know -- is a narrowing of the partisan divide over environmental protection. Folks in red states want clean water and clean air, and they enjoy natural spaces, just as we all do.

“At Earthjustice, we work all over the US, including Texas, Oklahoma, and Appalachia. We also work with tribes that have many members who are politically conservative. Taking on a diverse range of clients, and setting up local offices across the country, lets us work with communities to address the problems that matter to them, whether it’s drilling behind their kids’ elementary school or companies dumping toxic wastes near their homes. I hope we can encourage the public to see environmental protection as not about politics but about what they and their neighbors value. Conservation should not be a red vs blue issue, and it would make a huge difference if we could move in that direction.”

I agree. We should be much more aligned on land use policies across the states than we are today. I hope that Freeman and Haggerty and others like them are successful with the work they are doing, which can forge common ground, speed the energy transition, and preserve our natural spaces.

Notes and References

1. This report from Headwaters Economics indicates that revenue from oil and gas leases on federal lands amounts to almost 10% of Wyoming’s total state expenditures.

2. It is well worth reading this short writeup by the Center for American Progress’ Mark Haggerty and Nicole Gentile about how financial dependencies on fossil fuels are slowing the energy transition and handicapping rural America. This slightly longer article by Haggerty reviews a number of specific examples of incentives gone awry. Haggerty briefly describes some more successful local policies here, and outlines a possible federal policy here.

Current Climate Data (March 2022)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

Texans have been asked to conserve power 3-8pm each day this weekend because hot weather and gas plant failures have put the power grid in jeopardy. Texas energy consultant Doug Lewin explains that ERCOT’s inaccurate forecasting, which does not account for the impact of climate change on today’s weather; the lack of energy storage on the grid; and the absence of incentives for energy efficiency and demand-response have all contributed to this early failure. It is also the case that Texas has limited ability to import power from other states. What does this augur for the coming summer?

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be edited or removed.

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.