Palo Alto’s electric grid was designed decades ago for homes that used relatively little electricity. Marshall explained that it’s “very typical” for a utility pole with a 37.5 kVA transformer to support around 15 households. What that means is those homes could consume an average of about 2400 watts. Think one toaster plus one hair dryer. You can imagine that as households add heat pumps and EV charging, which tend to run at several kilowatts (kW) for multiple hours, the utility would need to upgrade the transformers and the lines that feed them.

An old electrical panel from a 1950’s Palo Alto home reflects the lower electricity needs back then.

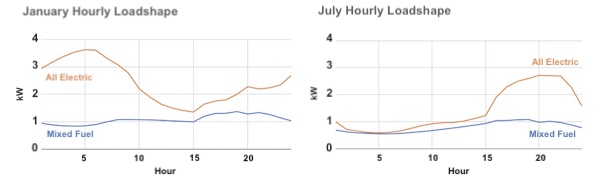

A preliminary study that the utility supervised in September 2020 modeled the impacts of electrifying Palo Alto’s 15,000 single-family homes. It found that heat pumps would result in additional demand on winter mornings, around 2-3 kW per household. More power would be used for air-conditioning on summer afternoons as well. The peak demand, which is what the electrical grid must be designed to handle, would grow to over 2.5x its current value (from 1.4 kW to 3.6 kW) if all homes switched to electric heat. You can see the new peak, on winter mornings, in the chart below.

Peak load will increase when homes are electrified. Source: City of Palo Alto Utilities (2020)

Electric vehicles also result in significant additional demand, but if the charging is well managed that demand need not affect peak capacity. (The EVs can charge at off-peak hours.) The study modeled both optimal charger management (no impact on peak load from EVs) and a typical night-time charging situation, where a two-EV household would add about 1.2 kW on average for each hour between 9pm and 6am.

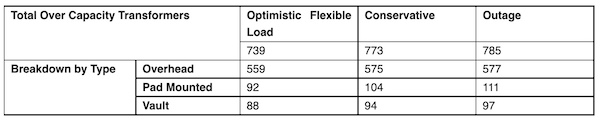

The study concludes that if all single-family homes in Palo Alto are electrified -- heating and transportation -- then virtually all of the estimated 797 transformers in the city that serve single-family homes would need to be upgraded, as well as about 20% of the secondary distribution lines and 25% of the feeder lines.

Virtually all of the transformers serving single-family homes in Palo Alto would need to be upgraded if the homes were all electrified. Source: City of Palo Alto Utilities (2020)

Marshall is also concerned about the potential for an even bigger demand peak after a prolonged outage. He explained that when a lengthy power outage is resolved, many appliances come on at full power across all impacted households at the same time. The study looks at this situation and estimates a peak demand of 8.5 kW per household, much greater than today’s 1.4 kW peak or the estimated 3.6 kW winter morning peak for normal operations.

Modernizing a grid involves more than just increasing capacity. We want to better support two-way flow (e.g., EV batteries discharging to the grid when there is a Flex Alert) and we want to improve grid reliability. Technology is rapidly evolving in these areas, as are tools to better secure the grid and to ensure the quality of the power supply (e.g., frequency regulation) as more households become generators as well as consumers of electricity.

The question is, can Palo Alto walk and chew gum at the same time? Can we upgrade our grid while we electrify buildings and transportation? Marshall comes down a hard “No” on this, particularly in the context of the aggressive 2030 goal. In a fairly black-and-white presentation, he outlines Option 1 and Option 2. Option 1 is business as usual, where we upgrade the grid as we go. This can result in inefficient upgrades, haphazard rollouts of new technology, extra expense, and customer delays. With a dearth of qualified staff to do the work, or even to manage contractors, Marshall states that the electric utility simply would not be able to keep up with the work needed if the city pushes to electrify all single-family homes in the 2030 timeframe. It can barely handle the level of demand today. In his preferred Option 2, the city postpones pursuing its 80x30 goal while the utility contracts with experts to design a 21st-century grid, updates the larger components (substations and main feeders) as needed, gets contracts in place for the smaller upgrades, and then updates the smaller components in sections, at which point targeted electrification promotions could roll out. He suggests that delay would be 3-4 years.

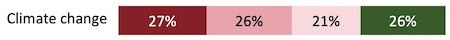

I don’t know if it was my imagination, but some of the Commissioners seemed positively relieved to hear this, as though they are finally in possession of a solid excuse to put aside the politically challenging task of equitably electrifying Palo Alto’s single-family homes by 2030. Councilwoman Allison Cormack also retreated quickly to suggesting that we could hopefully run some pilots during this multi-year planning process. She defended this approach by pointing to a recent survey of Palo Altans showing less than universal support for addressing climate change. (1)

Other Commissioners pushed for a better set of options. With so little information in the presentation it was difficult to offer concrete suggestions, or even to gauge how close we are to having major problems. EV adoption is taking off regardless of whether the city promotes it, so will we have to tell people they cannot charge their cars at home? If hot and smoky weather persists as the new summer normal, and homeowners are forced to keep windows closed at night, will we have to ask them to cut back on air conditioners? Rapidly increasing electric demand may be coming whether we are ready or not.

The utility could consider requiring the use of smart chargers for EVs, or at least making them available at very low cost. Same for smart thermostats. Aggressive pricing models can swing use away from peak times. (While Palo Alto does not have the requisite smart meters yet, it could roll out the first batch next year to all-electric homes or to homes in grid-constrained areas.) Commissioner John Bowie suggested that aggregating upgrades could save effort and expense. Lena Perkins, a Senior Planner at City of Palo Alto Utilities, is interested in the potential for smart panels to make the best use of constrained supply to homes. There are many types of fairly established technologies that can mitigate the need for (and expense and delay of) grid upgrades. There is no doubt in my mind that an Option 3 exists that can support a considerable amount of electrification without the need to wait for a full grid update.

I was disappointed that Marshall did not inform or engage more with his presentation. It was not designed to educate or solicit meaningful feedback. Instead, the goal seemed to be to draw a line in the sand. “Listen to us. You can’t do this without infrastructure. Stop the madness.” Commissioner Lisa Forssell asked directly if Infrastructure was being ignored, and Marshall’s answer was yes, in particular with regard to the 2030 timeframe. If that is the case, the city must do better. Marshall suggested that moving the electrification efforts under the utility would help. (2)

One of the biggest impediments to progress on the city’s aggressive climate goals is the utility’s difficulty hiring qualified staff. Marshall said that the utility is “very understaffed in both engineering and operations on the electric side today”, going so far as to say that engineering is “half staffed”. He explained that it is “very difficult to attract people to come to work in Palo Alto” and cited the high cost of living. “If we get somebody, they’re typically already here.” He said it is especially hard to find electrical engineers, since they are in high demand. PG&E is doing a lot of hiring with their wildfire hardening and undergrounding efforts. Marshall claimed that PG&E is offering linemen on the Peninsula a $50K signing bonus. Utilities Director Dean Batchelor concurred, saying that “It’s really tough to find people who will come here.” He talked about his recent experience recruiting at San Luis Obispo, one of two schools with power program degrees (the other is Sacramento State), and noted the fact that it will take four years to train the recruits they do attract. The Commissioners all wanted to understand these challenges better, and agreed that quality people are needed to achieve the city’s goals.

It is no surprise that Palo Alto’s decades-old distribution system needs work. And it is no surprise that the 80x30 goal, set in 2016, would force that issue. I’m not entirely sure why this is only coming up now, but in a way it’s a good sign. It’s clear that the city and the utility are taking electrification seriously. The question of “if” we electrify was never discussed, only “when”, and even then it was a matter of a few years. The challenge of making this pivot in a world of rapidly evolving grid technology was also clear. Marshall expressed a desire to “assess all technologies” and examine “all the different things out there we could do”. That is laudable but also problematic, because this is a quickly evolving space. What bets should Palo Alto place, and when, to support and, yes, drive adoption of the most impactful emissions reductions while following a safe and conservative plan to update our grid? That is a big question, and one that I hope that we will lean into together so we can accelerate our efforts as the world continues to warm.

Notes and References

1. In a survey of 801 Palo Alto voters done at the end of 2021, results showed that 53% of voters think climate change is an “extremely serious” or “very serious” problem, 21% think it is “somewhat serious” and 26% consider it to be “not too serious”.

“Extremely serious” responses are shown on the left and “not too serious” on the right.

In addition, when voters were asked what rationale might be acceptable for a tax measure to raise more revenue, 68% felt climate change was a “very acceptable” or “somewhat acceptable” rationale, while 29% said it was “somewhat unacceptable” or “very unacceptable”. (The rest, shown in gray below, didn’t know.)

“Very acceptable” responses are shown on the left and “very unacceptable” on the right.

2. Commissioner Greg Scharff weighed in as well on governance, stating that he would like to see the UAC have decision-making power rather than just being an advisory board. He pointed to the City of Alameda’s Public Utilities Board as an example of that.

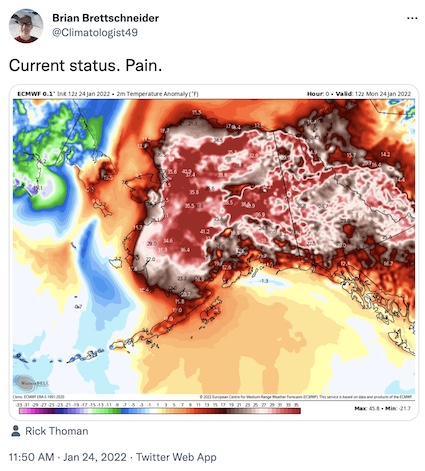

Current Climate Data (December 2021)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard

30+ degree temperature anomalies all over Alaska on January 24. Source: Twitter

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.

Comments that are written in batches by people/bots from far outside of this community are being removed.