Yet state law requires that we succeed. When regulators agreed to close Diablo Canyon, Jerry Brown signed a law stating that the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) must “avoid any increase in emissions of greenhouse gases as a result of the retirement of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant.” Was Governor Moonbeam suffering from undue optimism? A nuclear advocate quoted in Time magazine would likely think so, characterizing net-zero ambitions that preclude nuclear energy as “a lot of wishful thinking, a lot of fingers crossed.”

So I read over the proceedings to see how the CPUC is taking action on this. To date California has been very effective at reducing emissions on the grid, so I wanted to understand how they are going about this difficult task.

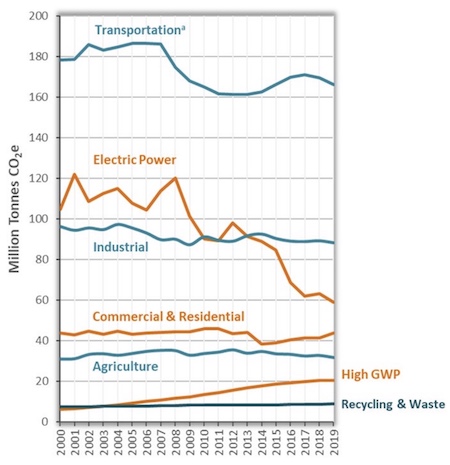

California emissions by sector, 2000-2019. Source: CARB (2021)

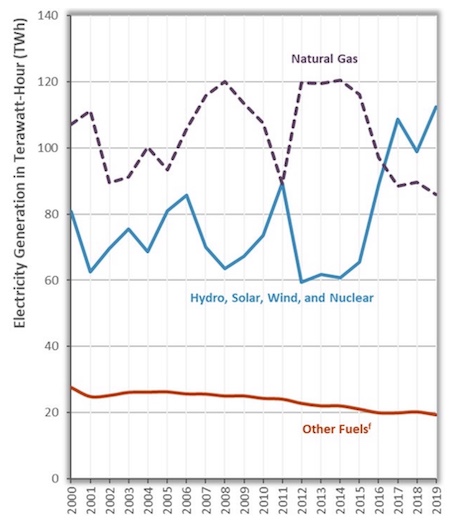

California has reduced power sector emissions in part by evolving in-state generation to rely less on gas and more on low-carbon power sources, especially over the last six years. Our imports have also gotten much cleaner.

California’s in-state electricity generation, 2000-2019. Source: CARB (2021)

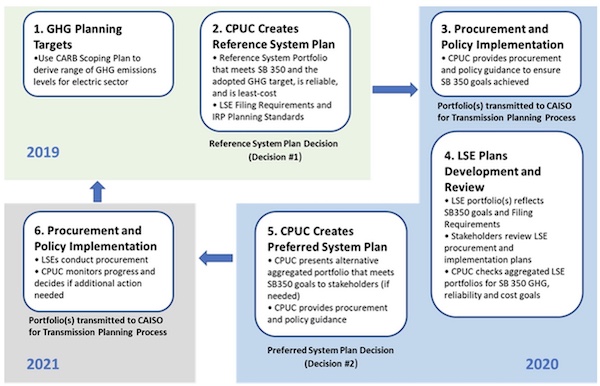

California has accomplished this by engaging in intensive planning across several state agencies. The legislators and California Air Resources Board (CARB) establish emissions goals for the electricity sector and provide guidance on how we can achieve them. The California Energy Commission (CEC) produces reports that, among other things, forecast electricity demand by looking at trends in electrification, climate, efficiency, and energy tech. The CPUC takes this information and works with power providers (e.g., our utilities) to formulate a “reference” plan that will meet the requirements with good reliability and low cost. The power providers use this as guidance for their individual plans, which the CPUC then collects and analyzes to see if the aggregate plan is suitable. The CPUC makes adjustments as needed, then produces a “preferred plan” that the power providers can work with to sign contracts. The California Independent System Operator (CAISO) participates throughout to determine what transmission is needed.

CPUC’s Integrated Resource Planning process for the 2019-2020 cycle. Source: CPUC (2019)

The question is, how did the Diablo Canyon shutdown wend its way through this process? Did it sneak by unnoticed? Was it accounted for but sloppily? Was the modeling overly optimistic? Or did it get a critical look? It’s safe to say that it was carefully analyzed, but not without some foot-dragging and some contention. Here is how it played out.

In 2018, after years of discussion, the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant was directed to shut down in 2025. PG&E said it was going to be expensive to retrofit the plant to comply with marine water regulations; it no longer needed the power (customers were switching over to Community Choice Agencies (CCAs) like our own Peninsula Clean Energy and Silicon Valley Clean Energy, as well as adding more energy efficiency and rooftop solar); and the plant’s steady (inflexible) operating profile meant that it would increasingly force cheaper renewables offline. Energy models indicated there were better alternatives. When the CPUC planning cycle began in 2018, the analysis was clear that the state would be able to meet its emissions goal of 46 million metric tons (MMT) by 2030 without Diablo Canyon, and that should be good enough for Jerry Brown. The report did suggest that some of the renewables replacing the nuclear energy should be bought prior to shutting the plant down in order to take advantage of federal tax credits, which would save taxpayers some money.

This generated robust commentary during the discussion of the report. Comments came from utilities, renewable energy providers, natural gas associations, friends and foes of nuclear energy, and more. There was some debate about whether the right approach was to buy early for tax credits or buy later and wait for prices to go down. (2) But one of the more impactful responses was a petition from several organizations (3), referred to as the Joint Parties, that pointed out the CPUC plan omits any specific ask of power providers to replace the power from Diablo Canyon. The petition suggested that we might be able to do better than 46 million metric tons if we kept the plant running, so the argument that “we’ll meet our goal” is not enough to uphold the law. Some organizations worried that buying renewables prior to shutdown would lead to an emissions bump at plant closure, which we want to avoid. The CCAs and some others disagreed, saying that the state’s modeling effort was fine and there was no need to explicitly identify clean energy purchases to balance Diablo Canyon’s output.

In April 2019, the CPUC filed a follow-on decision laying out the plan that power providers would need to follow for the coming years. In it they directly addressed the Diablo Canyon controversy and largely held their ground. They disagreed that there should be no increase in emissions “at the very moment that the Diablo Canyon units go offline”. They explained: “Expecting an exact one-for-one replacement of energy from Diablo Canyon that is timed perfectly to coincide with the Diablo Canyon closure would be a costly and illogical way to ensure that the emissions trajectory of the electric sector is on track to meet the State’s goals.” However, the CPUC did express some concerns about reliability and whether the CCAs and other power providers would replace the 24x7 power from Diablo Canyon with more variable renewables that would not provide energy at critical peak hours. They stated: “... if anything we are concerned that the replacement power procured mostly by CCAs will not represent as reliable a resource as Diablo Canyon has proven to be over the decades.” They go on to say: “We will require each LSE (Load Serving Entity, aka power provider) serving load in PG&E’s territory to address how it will replace the characteristics of the Diablo Canyon output with either flexible baseload and/or firm low-emissions energy. We will not, however, allocate a specific replacement capacity or energy to each LSE.”

Around this time, the CPUC was getting concerned about procurement (i.e., power purchases). In the past, the agency had worked mainly with three big investor-owned utilities (PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric) to purchase needed power supplies. The CPUC was able to direct power purchases and had good visibility into the transactions.. But with the growing popularity of local power providers, the CPUC now had to work with many smaller utilities, each with their own philosophies and goals as well as different levels of transparency. These smaller agencies also tended to have less ability to make large investments.

The CPUC was now faced with building a reliable and efficient system across many newer and smaller operators while managing a quickly changing energy landscape. Concerned about the pending loss of 2,300 MW for Diablo Canyon and 4,200 MW for retiring gas plants during this transition, the agency added some additional process to track and facilitate procurement. They also developed a “backstop” mechanism whereby the big investor-owned utilities would contract for power in the event some providers were unable to achieve their plan. Between looking at these near-term stressors and dealing with the outages of summer 2020, it wasn’t until February 2021 that the CPUC issued a report addressing procurement and the reliability of the power supply in the 2024-2026 (“mid-term”) time horizon.

The CPUC had many causes for concern at this point. They wrote: “The potential for reliability challenges is driven by several factors, including the planned retirement of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Plant, planned retirement of older natural gas plants including those using once-through cooling, suggested modifications to the planning reserve margin, changes in resource availability throughout the west, updated effective capacity accounting, and an updated demand forecast.” The summer outages and increasing prospects for extreme and widespread heat had the analysts seeking a larger planning reserve margin. Hydroelectric resources strained by the drought, combined with more emissions standards in western states, could restrict clean imports. Demand is forecast to increase with successful electrification efforts. And the amount of power available at peak times is diminishing as the peak moves away from times when solar and even wind are plentiful. (4)

Around this same time, the Union of Concerned Scientists issued a report criticizing the CPUC’s approach of “As long as we hit our emissions target, we know that Diablo Canyon’s retirement had no impact”. They showed that the emissions target that CPUC had chosen, namely 46 MMT in 2030, was not compatible with a “no impact” result. If Diablo Canyon were not shut down, emissions would be only 43 MMT based on the planning guidance to date. They urged a lower emissions target and/or dedicated resources added to replace Diablo Canyon’s power.

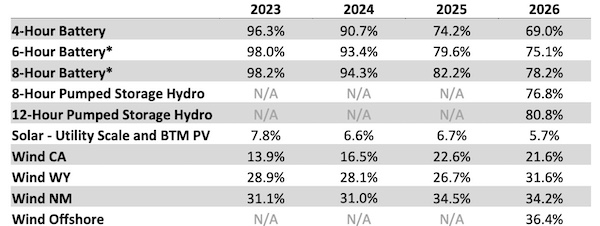

CPUC’s February 2021 report moved in this direction. It proposed a 7,500 MW special procurement, and critically that 7,500 MW was required to be “net qualifying capacity”, namely power that would be available at peak times. Solar farms could contribute only minimally towards it, and wind farms would also be heavily discounted. The table below shows recent guidance for these discounts, which get more aggressive over time as a particular type of power becomes more prevalent on the grid.

These incremental Effective Load Carrying Capacity (ELCC) values reflect the ability of a resource to prevent power shortages. (4) Source: Astrapé Consulting and E3 for the CPUC (2021)

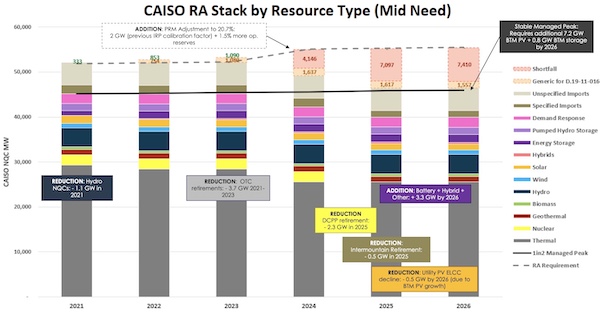

The chart below shows how the state forecast the grid’s “net qualifying capacity” over the coming years. It’s a little hard to read, but there are a few things to notice:

- The massive amounts of solar and wind on the grid contribute plenty of energy but generally little at peak times, so the corresponding bars on this chart are narrow. (They are the light orange and light blue bars, respectively.) Gas (grey) makes the dominant contribution, while nuclear (yellow) and hydro (dark blue) make a relatively large contribution among carbon-free sources.

- In 2021 (the first column) the state plans for a 1.1 GW reduction in hydroelectric power due to constrained supplies.

- In 2023 the state plans for a 3.7 GW reduction in thermal energy (gas plants retiring due to their use of once-through cooling).

- In 2024-2025 the state plans for a 2.3 GW reduction from the Diablo Canyon retirement.

- In 2025 another gas plant goes offline, taking 500 MW.

- And in 2025-2026, with the increased penetration of rooftop solar, solar becomes even less effective at addressing peak capacity crunches.

Analysis of available net qualifying capacity by year. Source: CPUC, slide 27 (2021)

Although the state has some additional peak capacity coming online, mainly in the form of batteries, the analysis still shows a large, approximately 7,500 MW gap between what the planned resources can handle and the projected peak (the dotted line). The shortfall is shown in a salmon-colored bar at the top.

Reviewers were “quite divided about the reasonableness” of this analysis. Some, including most of the utilities and power providers, felt it was well balanced. Others felt it was too conservative and therefore too costly, and advocated for reducing planning margins and asking for less capacity. Still others, including CAISO (which did its own analysis) and several environmental organizations, felt the proposal was too risky. They argued that the state should plan for a “high need” rather than a “mid need” scenario, citing a need for higher reserve margins due to extreme weather, greater reductions in the availability of clean imports, the potential for stricter emissions targets and more gas plant retirements, and the severe consequences of falling short.

Ultimately, in June, the state agreed with those who argued that we should plan for a “high need” scenario, saying: “As the rotating outages required in August 2020 have demonstrated, we are not in a business-as-usual situation on the electric grid in California. The electricity market is changing rapidly in many respects, including the large number of new LSEs (power providers), the recent major shifts in the resource mix, a great deal of weather- and climate-change-driven uncertainty, as well as the increasing acceleration of electrification of building and transportation end uses.” They also cited the likelihood of the agency’s adopting a more aggressive emissions goal for the power sector (38 MMT by 2030 instead of 46 MMT), which is better aligned with this scenario.

The final decision issued in June 2021 requires power providers to procure a record-setting 11,500 MW of net qualifying capacity power (power available at peak times), all non-fossil, all zero-emission or renewable. The CPUC calls this “an unprecedented, but necessary, quantity of clean energy procurement that will ensure reliability in the mid-decade, help California achieve its climate goals, spur the development of the clean firm resources needed for deep decarbonization, and create thousands of green energy jobs in California.” They also specifically address the Diablo Canyon retirement. They require “2,500 MW of zero-emitting generation, generation paired with storage, or demand response resources” to replace the power from that plant. They further clarify that “These resources are expected to be largely incremental renewables paired with storage (physically and/or contractually) that can deliver continuous power, at a minimum, during five hours (5 p.m. through 10 p.m.)”

Given the considerable analysis and discussion, I think it’s fair to say that the issue of Diablo Canyon’s retirement got ample attention during the planning process, and has been well incorporated into the state’s plans. What remains to consider is the ability of our power providers to procure the needed resources in a timely fashion, and their ability to do so at reasonable cost. That will be the topic of my next blog post, so stay tuned!

Notes and References

1. See the California Energy Commission’s 2020 Total System Electric Generation report.

2. As you can imagine, the renewable energy providers preferred buying early, while the CCAs on the hook to buy energy preferred to wait.

3. The Joint Parties were: Friends of the Earth, Natural Resources Defense Council, California Unions for Reliable Energy, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company.

4. You can find a good explanation of this phenomenon here, from Senior Energy Analyst Mark Specht of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Current Climate Data (October 2021)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Quote of the week, from a San Francisco Chronicle editorial in the context of our severe and on-going drought: “But conservation won’t be enough. We still need to diversify our water portfolio. Thankfully, there are rivers upon rivers of untapped, drought-resistant fresh water waiting to be captured — our treated sewage outflows.”

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.

Comments that are written in batches by people/bots from far outside of this community are being removed.