Palo Alto doubled down on its ambitions in the last year, committing considerable staff time, meeting time, and budget to analyzing how it can achieve its goal. Vice Mayor Pat Burt spoke for much of Palo Alto City Council recently when he reflected that climate change is not just an existential threat, but a serious present-day threat to public safety and health, and an alarming economic risk. “We really don’t have a choice.” Burt said about taking forceful action to reduce emissions. “It is foolish to not do what's necessary, to act while we still can. The consequences far exceed the investments that are necessary.”

The latest analysis shows that Palo Alto, and specifically people driving in or owning homes in Palo Alto, will need to take significant steps over the next 9 years to reduce and eliminate their use of gasoline and natural gas within the city. Will the community support this? What will it cost? And how should we equitably manage the impact?

A Brief Recap

Palo Alto set a goal five years ago to reduce emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2030. This so-called “80x30 goal” was based on science indicating that this level of reduction is necessary to keep the global temperature increase to 1.5C. That guidance has not changed, and City Council reaffirmed its commitment to addressing climate change just a few months ago, listing it as one of the top priorities for the city. Councilmember Greer Stone shared his belief that “There is no greater thing we can be doing than working on the issue of climate change.”

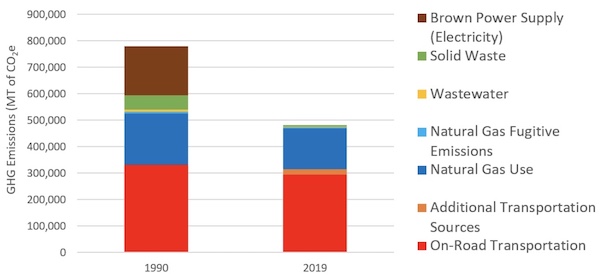

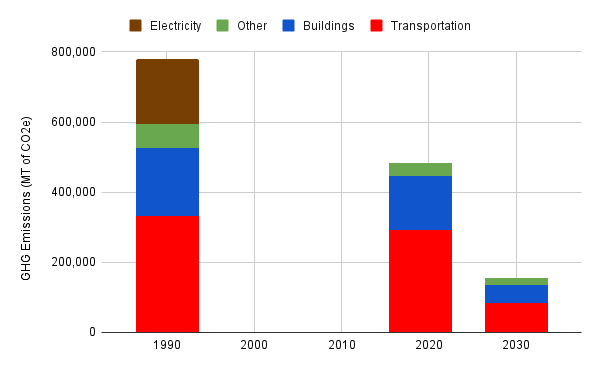

Today city emissions are 38% below 1990 levels despite a 24% increase in population. Much of that is because Palo Alto switched to carbon-neutral electricity, but impressively natural gas use dropped by 21% (e.g., from stricter building codes), and road transportation emissions dropped by 11% (e.g., from stricter fuel-efficiency standards).

Emissions dropped 38% from 1990 to 2019 despite a 24% increase in population. Source: Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

Time is running short, however, as we face even steeper reductions. It took us thirty years to reduce emissions by 38%, but we now have just nine years remaining to make a 68% reduction.

Palo Alto aims to reduce emissions by 68% in the next nine years.

With committed city staff, residents, and local businesses, plus help from state and federal governments, we can get a lot closer than we are now. One resident expressed a concern that “The low-hanging fruit are gone.” I disagree. We have some terrific transportation options in both new and used EVs and e-bikes. On the buildings side, heat pumps for hot water and mini-splits for air conditioning (and heating!) are gaining a lot of traction. In my opinion, we have new kinds of low-hanging fruit. But Councilmember Alison Cormack adds that “If we’ve picked the low-hanging fruit, we need ladders.” The task at hand for the city is to motivate the picking and to design and build ladders to make it easier.

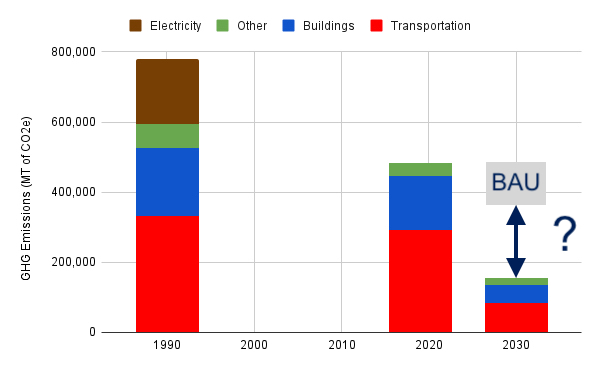

If We Do Nothing, aka “Business As Usual”

Current city and state policies, and even some aspects of the pandemic, provide something of a tailwind. Cars will get more efficient, more people will adopt EVs (1), many people will telecommute a few days a week (2), and our all-electric building code for new residences will apply to more homes. The city report on our 80x30 planning estimates that we would see a 23% reduction in emissions from 2019 levels by 2030 just from existing policies. That’s a nice one-third of what we need.

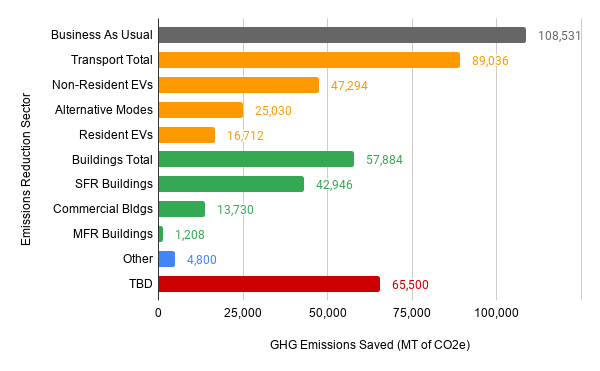

“Business as Usual” policies, shown in gray, get us one-third of the way to our goal by reducing emissions by 109,000 MT CO2e. Source: Adjusted “Business As Usual” analysis from Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

The question the city is working to answer is, how do we go well beyond this “business as usual” forecast, quickly, and how do we pay for it?

We Must “Do Everything”

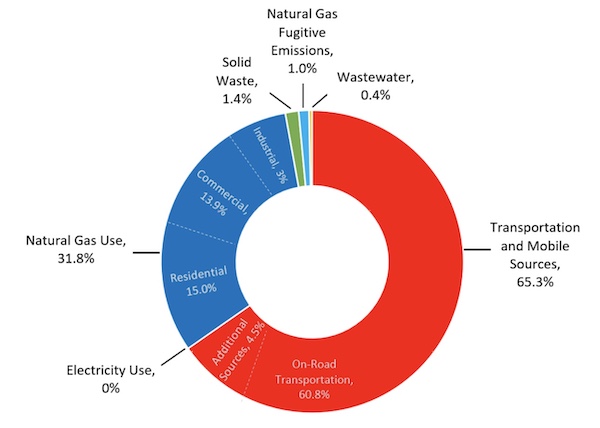

Palo Alto’s 2019 emissions look like this. Not surprisingly, it’s mostly transportation and buildings. (3)

Palo Alto’s 2019 emissions. Source: Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

The analysts working on the 80x30 plan initially believed they would have a range of reduction options to run by City Council. They found, however, that the simple picture above hides complexity and constraints that limit what we can do. Brad Eggleston, Director of Public Works for the City of Palo Alto, said that one of the surprise findings to come out of the analysis was that “We need to do pretty much everything we can” to hit this goal, and even then the analysts are coming up short. To date the best plan we have yields a 72% reduction by 2030 (which does yield an 80% reduction by 2037).

Why is it so hard? One complication is that many of the transportation emissions are not from residents. Palo Alto is a destination for many workers and visitors. The city’s total population (workers, children, and retirees) is around 70,000, but there are about 100,000 employees from out-of-town, as well as many visitors. If all residents stayed out of gas cars entirely, it would address just a small fraction of the emission reductions we seek. Palo Alto needs to find ways to encourage in-bound commuters and visitors to adopt EVs, e-bikes, and alternative modes of transportation, or to telecommute. This is not easy, so the plan sets a very high bar for EV adoption among residents, namely 85% of all new vehicles purchased by Palo Alto residents are EVs by the end of the decade, up from an already top-in-the-nation 30% today. (4)

Another complication is that over half of our building emissions come from non-residential sources, many of which are particularly difficult and expensive to electrify. Moreover, among residential buildings, over 40% of Palo Alto’s housing stock is in multi-family buildings, which are also costly to electrify. While there are some exceptions (packaged rooftop HVAC systems have a low-cost replacement), analysts concluded that the city has to focus on single-family homes for building emissions reductions. Specifically, the impact analysis assumes that 100% of single-family homes in Palo Alto will be retrofitted to all-electric by the end of the decade. That means retrofitting thousands of such homes every year.

These retrofits generally do not pencil out in our city because of high construction costs coupled with a temperate climate. Construction is very expensive here, so retrofit costs are high. Those costs are especially difficult to recoup with lower home energy bills because our temperate climate means the bills are not that big to begin with. Most residents have no air conditioning, and we need only modest amounts of heating. The effect is that full electrification retrofits are generally money losers in this area.

Finally, there are legal concerns around some of the measures the city might roll out. For example, Palo Alto could make electrification more appealing by raising its gas prices and lowering its electricity prices, but exchanging funds across utilities is legally problematic. Palo Alto might aim to attract more contractors by setting an end date for natural gas use, but that could result in a potentially time-consuming and expensive lawsuit, as happened to Berkeley when restaurants sued over gas hookups. Charging a toll to gas cars driving into Palo Alto? Raising the price of registration for a gas car? Increasing the parcel tax to fund electrification? All could be subject to legal challenge. The report notes: “For example, while a parcel tax is one legal option, applying the revenue raised from that tax to fund improvements on private property is unprecedented.” Palo Alto City Attorney Molly Stump is careful to say that we don’t aim to back away from all legal concerns, but we should understand the risk exposure of various options. Help from the state could be very valuable here.

What Does “Everything” Look Like?

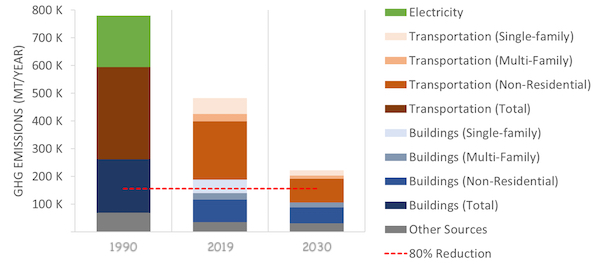

The analysis that Palo Alto undertook tried to identify feasible changes (doable and effective in the next nine years) that would provide the most reductions for the dollar. You can see the results in the third column below:

This chart shows a strawman plan to achieve much of the 80% reduction by 2030. Source: Attachment D of the Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

The plan derived by the analysis consists of the following elements. Keep in mind that the relative contributions listed below are all beyond the 109,000 MT CO2e in “Business As Usual” reductions that are anticipated from existing policies, which include considerable EV adoption as well as telecommuting.

Transportation

- Residents adopt even more EVs (16,712 MT CO2e). The strawman plan has 85% of new vehicle purchases being EVs, up from 30% today and 50% projected as “business as usual”. Because our car fleet takes a while to turn over, even this high level of adoption by 2030 would leave more than half the vehicles as gas-powered. By the end of the decade, 44% of all vehicles in the city are EVs, with one-half of all vehicles owned by single-family residents being electric, and one-third of all vehicles owned by multi-family residents. City assistance purchasing used EVs, a special EV charging rate, and charger rebates can help with this.

- Visitors and in-bound commuters adopt EVs (47,294 MT CO2e). The analysis has 40% of commute trips into Palo Alto and 30% of visitor trips into Palo Alto being made by EVs, up from 3% today. The reductions in emissions projected in this category are among the largest modeled, with all of this adoption exceeding “business as usual”. I asked city staff why they believe this is feasible, and the response was that Transportation Demand Management programs at local businesses and other organizations will contribute. Municipal parking policies can also have an impact. The level of reductions here suggest that it will be very inconvenient and/or expensive to drive a gas car into Palo Alto. Is the thinking that lane management policies on 101 will make it increasingly inhospitable for gas cars? I would like to see more of the city’s thinking around this very large reduction in gas cars coming into the city.

- People stop using cars (25,030 MT CO2e). Vehicle miles traveled by residents, commuters, and visitors is reduced by 8% to 11% in the plan. Car-free streets, safer bike lanes, and transit accelerators like preferential signaling and rapid bus lanes can help here. The projected savings here are very significant, especially given that bike trips are generally short. Can we make transit work more efficiently into and out of Palo Alto? I would like to better understand the thinking behind this, and how many trips we expect to convert from car to bike or to transit.

Buildings

- Single-family homeowners electrify (42,946 MT CO2e). The analysis assumes that 100% of single-family homes are electrified, with few exceptions. On-bill financing can be a big help here, as can volume discounts, contractor buy-in, simplified permitting, and some amount of community-wide funding.

- Rooftop HVAC units are converted (13,730 MT CO2e). 100% of commercial rooftop HVAC units are electrifie, with few exceptions. This is essentially a cost-neutral switch.

- TBD (65,000 MT CO2e). It remains to be determined what further reductions can be made to close the gap to a full 80% reduction from 1990 levels by 2030. The gap is large. City staff is looking closely at options for multi-family and commercial buildings. Some direction around new construction or specific appliances might apply. Staff will also be looking at the impact of different land use policies.

Relative contributions of different components of the plan are shown here. Source: Attachment D of the Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

How Might We Pay for This?

Palo Alto estimates the full cost of achieving these emissions reductions to be about $750 million. (5) If we assume that financing is available, this nets out to about $53 million/year. (6) To put that number in perspective, the city collects about $175 million/year in utility bills. If everyone’s utility bill were to go up by one-third, the city could pay for 100% of this work.

There is some appeal to having the city cover costs. Homeowners might otherwise adopt an EV (because it saves money) but choose not to electrify their homes (because it costs money). With the city covering the costs, many more homeowners would take the additional step of switching to a heat pump. The city has good access to financing, may be able to negotiate bulk discounts, can develop a contractor base, and so on. But how can it fairly collect the needed revenue?

Raising utility bills by 33% across the board is not a great plan. Some community members cannot afford such an increase, while others might see little value to justify the additional expense. The city is instead looking at a more careful allocation of expenses, perhaps using a parcel tax or a carbon tax. (7) It’s worth watching this video to understand how the planners are thinking about dealing with the costs of reducing emissions.

In one exploration they describe, all low-income households, non-profits, and small local businesses would be exempt from paying for city-sponsored emissions reductions. Others would be assessed via parcel tax in the following ways:

- $300/year for single-family homes ($25/month)

- $120/year for multi-family homes ($10/month)

- $1.35/square foot for commercial buildings (8)

This is just one of many options and it is important to understand, as Assistant Director for Utilities Resource Management Jonathan Abendschein cautions, that “there are a lot of assumptions in this model, and it is an order of magnitude estimate rather than a precise estimate”. Furthermore, no change like this can be made without substantial engagement with stakeholders and ultimately voter approval.

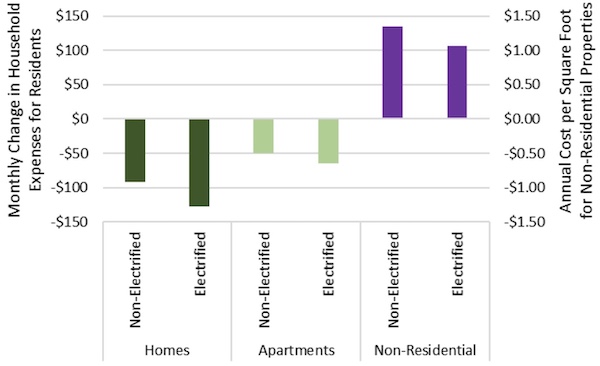

This particular exploration has residents saving money overall, if you include the savings they gain from switching to an EV. (9) But commercial businesses see primarily an added expense, albeit a smaller one than they would incur if they were to electrify their own buildings. The parcel tax mechanism functions in a sense as a high-quality local carbon offset for these commercial businesses, though a relatively expensive one (I would guess around $100/ton).

In one exploration of a parcel tax increase by the city, residents can save money by switching to EVs and electrifying their homes, while commercial businesses would incur a cost. Source: Palo Alto Staff Report (April 2021)

A Carbon Neutral Delay

Along those same lines, one option the city will be looking at in the coming months is the possibility of delaying some of the higher-cost reductions we face and instead achieving carbon neutrality by funding reductions elsewhere that are more cost effective. This approach gets mixed reviews from environmental economists, with most preferring local reductions that can be verified. An extreme example of these emissions offsets is if someone were to fund planting some trees in a distant country rather than electrify their home. Will the trees be planted? Would that area have stayed tree-less without the funds? Is there sufficient water for trees to grow? Will they live sufficiently long? And is it appropriate for the wealthy to pay for their high-emission lifestyles by outsourcing their emissions reductions, even if it’s at lower cost?

The offsets the city considers will likely be much more local and verifiable than in that example. For example, what if it costs half as much to reduce emissions in the East Bay or in the Central Valley? Would we be better off paying to electrify another area instead of investing larger amounts for lower impact in Palo Alto? An analysis using such a regional lens will be interesting.

What Next?

Mayor Tom Dubois believes the report may be too conservative in laying out near-term actions that can have good impact despite being lower cost and voluntary. He urged city staff to move more quickly where they can. “There is no time to waste. These are really steep targets.” Vice Mayor Burt suggested moving quickly to understand the degree to which residents will not only opt to make changes for themselves, with some city programs in place, but also contribute to a fund that will help others do the same. Burt observed that the city’s success with Palo Alto Green, an opt-in green electricity premium, indicates that a well-run program to take donations for electrification might have good traction. The utility has also accumulated $9 million to use in this effort (10).

Palo Alto can immediately use funds to expand its rebate program to electric space heating, EV chargers, electric panels, and more, with a focus on lower-income families. It can design a special electricity rate for all-electric homes and/or homes with EVs. The city can design a program to help buyers sell and purchase used EVs. Alternative transportation can be encouraged with better signage and parking for cyclists, as well as safer lane markings. On the building side of things, the city can provide on-bill financing, negotiate bulk discounts with contractors and suppliers, and simplify permitting. It can continue to work on reducing the installation of gas appliances in new multi-family and commercial buildings and in significant remodels of single-family homes. It can work to improve grid reliability and reporting.

I would like to see these concrete actions happen sooner rather than later. I worry about the lack of specificity around policies for some of the largest reduction targets, and I am skeptical that some can be achieved without regional action, which takes time. So I hope we will move early with those plans and policies that are straight-forward, and reward and celebrate the many in our community who will step forward to do their part and even more.

To learn more about the analysis that Palo Alto is doing to identify the best way to quickly effect a precipitous drop in its emissions, you can check out the staff report, a series of short videos, and a video of a City Council discussion. There will also be ample opportunities for community engagement.

Notes and References

0. The city is also working on adapting to climate change impacts such as sea level rise, but that is not covered in this post, which focuses specifically on emissions reductions.

1. This is aided by California’s initiative to sell no more gas-powered cars or light trucks by 2035.

2. Palo Alto estimates that about 50% of workers will telecommute two days per week. However, there is some debate about the consequent emissions reductions. According to the staff report, “The overall impact of remote work on GHG emissions is inconclusive. Some studies that account for factors such as increased non-work travel and home energy use have found remote work to have a neutral or negative impact on overall energy use.” The report goes on to say that some people might move further away from their workplaces, effectively adding to their emissions when they do need to go into work.

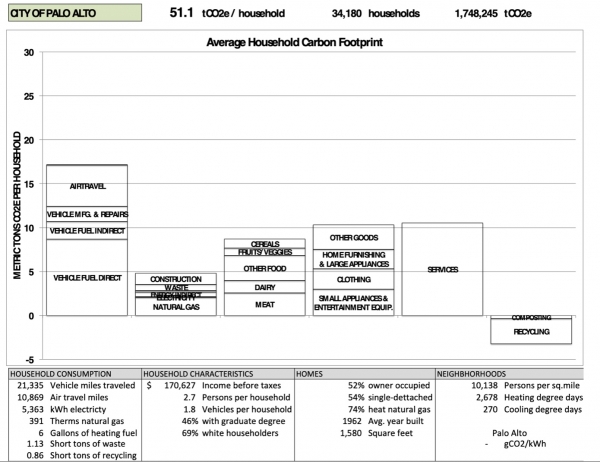

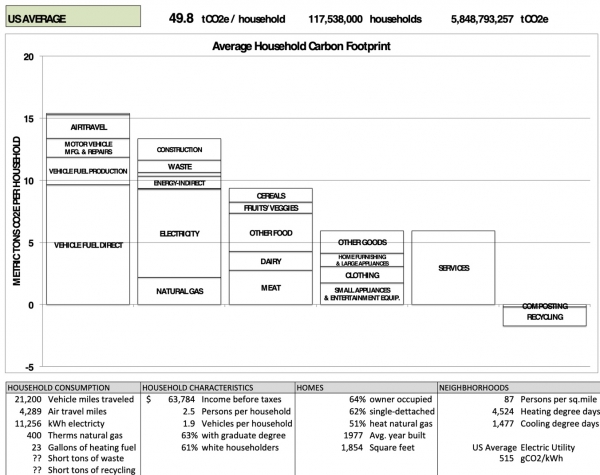

3. Palo Alto is reflecting only those emissions that are produced in the city itself in its calculations, which is common for city emission inventories. This means that Palo Alto emissions do not reflect indirect or consumption-oriented emissions, such as might accrue from things the city or its residents and businesses purchase or consume. The city is not campaigning for residents to eat less beef, fly less, or consume fewer goods. Those emissions are theoretically counted elsewhere (e.g., where the farm or factory or airport is), though domestic air travel is only aggregated at the country level and international air travel is its own category.

4. Palo Alto’s adoption rate for new EVs today (30%) compares with 8% in the state of California more generally, and 2.3% in the United States overall.

5. The cost does not include changes to the utility itself, for example to expand capacity or improve reliability.

6. Regarding the schedule of these payments, Assistant Director for Utilities Resource Management Jonathan Abendschein says: “In our analysis we assumed financing over the life of each charger installation or building improvement, with financing commencing at the time of capital investment, which could take place any time between 2021 and 2030. The last financing payments would be made before 2060 for certain, but the payments for financing for different types of improvements would end in different years depending on the life of the improvement and the year in which the improvement was made.”

7. The city seems to prefer a parcel tax assessment to a carbon tax because parcel tax income remains fairly stable, while that from a carbon tax would erode as people moved away from gas. Stable revenue is important when long-term financing is used.

8. The charge of $1.35/square foot represents about one-third of the utility bill for these customers, or about 2-3% of their overall rent (at $40-$80/sf).

9. The EV savings that are modeled are discounted by the higher price of EVs relative to gas-powered cars for the next few years. However, when price parity is achieved, the savings modeled grow commensurately and are used to offset building electrification costs. If a resident car buyer is also using those same savings to justify buying a fancier car than they otherwise would, those savings would be double-counted by the city and the resident. In other words, their electrification expenses will be higher than estimated by the city.

10. The utility has amassed about $6.6 million from the sale of Low Carbon Fuel Standard credits, which it receives for charging the many EVs in the city. These are to be used for promoting EV adoption. It also has accumulated about $2.5 million from selling cap-and-trade allowances that it receives for operating its own utility. These are to be used for general decarbonization efforts. The utility expects to receive on the order of $1-$2 million/year going forward.

Current Climate Data (March 2021)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

I love looking at all the low-water plantings around the area at this time of year. This is one of my favorites, at a nearby house.

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.