I was planning to do a blog post on nuclear energy so I was listening to some podcasts for background. I had found one, Titans of Nuclear, that had interviews with a variety of interesting people, so I had downloaded a few to listen to. One episode was an interview with Dr. Edwin Lyman, the Director of Nuclear Power Safety for the Union of Concerned Scientists. It was pretty long and I figured I would learn a lot. I guess I did, just not what I was expecting.

What I learned, really viscerally, was the degree to which an impatience with science, a lack of appreciation for statistics, and a disinterest in precise speech can lead to a complete breakdown in communication, even between ostensibly intelligent parties. The conversation is eye-opening. I encourage you to listen to it, starting around 14:30 where Lyman says that we want to avoid another Fukushima.

Dr. Edwin Lyman has worked for decades in nuclear policy after receiving a PhD in physics from Cornell. He is a well-regarded expert on issues including nuclear safety and security. The podcast host, Bret Kugelmass, is a nuclear energy advocate in Washington DC, where he has interviewed hundreds of people in the field for his podcast. He earned a masters in robotics from Stanford before beginning his advocacy work out of concern for climate change.

The two have different styles. Lyman is a careful, dispassionate communicator, like many scientists. He prefers to move between academic and practical spheres in a principled way, understanding the data before making policy decisions. Kugelmass is more impetuous, a passionate communicator, perhaps more interested in persuading than he is in learning. In the case of nuclear, he feels strongly that the industry is over-regulated, resulting in too much cost for too little benefit. These two were oil and vinegar. I am sure that Lyman felt Kugelmass was egregiously sloppy in his thinking, while Kugelmass felt that Lyman was obstructively ponderous and impractical.

I am sympathetic with both. I can imagine Kugelmass thinking “Look, if you are in a burning building, do you stoop to take the temperature of the doorknob before you open it and rush out? No, it’s not that hot, just go already!” At the same time, I can imagine Lyman responding “Look, I don’t care if you grab the doorknob or not. That’s a policy decision. Just don’t claim the doorknob isn’t hot.” The issue that I have is we shouldn’t have to choose between a science-based approach and speed. We should be able to act, and even act quickly, without disregarding facts. “Science suggests the doorknob is hot. Grab it with a towel or something on your way out or you may have to deal with a bad burn.”

The host’s impatience with and disregard for science is the core problem I have with this podcast. The at-best-sloppy and at-worst-deceptive arguments put forth by Kugelmass distort the facts and in my opinion constitute a much bigger roadblock to progress than the facts (and uncertainty) themselves. Here is how it played out.

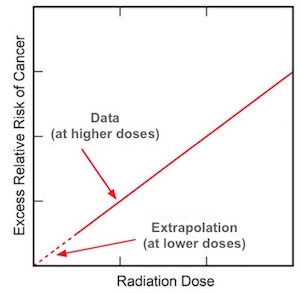

At the heart of much of the discussion was the basic question: “How much ionizing radiation is too much?” There are many studies demonstrating a linear dose-response relationship between the amount of radiation a person is exposed to and the amount of damage (e.g., cancer) they incur. When real-world events have exposed a large enough population to a large enough dose of radiation, this relationship is backed with statistically significant findings. The linear relationship is extrapolated to lower doses based in part on the biological mechanism by which ionizing radiation affects the body.

One of the initial exchanges was about this mechanism. Radiation can disrupt genetic material and cause tumors to form when the defective cells propagate. Lyman explains that the exposure works differently for different types of radioactive particles, and begins to talk about how some particles are so big they need to be ingested rather than go through skin. Kugelmass interrupts, questioning whether cell damage is inherently bad. “When I work out, I do considerable damage to my tissue also, but it makes me stronger in the net effect, at the end of the day. I’m literally destroying individual cells whenever I work out. And the same happens with radiation, on a micro basis…. Destroying cells doesn’t mean, on net, it leads to a cancer.”

How do you respond to a statement like that, essentially equating radiation exposure with exercise? Lyman methodically begins his response by distinguishing between cases in which tissue is destroyed (e.g., acute radiation syndrome) and cases in which genetic material is modified and propagated (e.g., cancer), and notes that they are talking about the latter. His communication is precise, while Kugelmass is more interested in making relatable statements that will appeal to his listeners. But if you want to make meaningful points on the possible beneficial impacts of low dose radiation, you need to be much more precise.

After this, the discussion was less about the mechanism by which radiation impacts the body and more about what we know about low doses of radiation. An analogy goes like this. Suppose you are panning for gold in a creek with a kitchen sieve. You don’t find anything after a day of looking. You declare “There is no gold here!” Is that right? What if you looked for longer? What if you were smarter about where you looked, or used a bigger sieve?” So you upgrade your equipment, talk with a geologist about where to look, and look for a full week. Still nothing. “There is no gold here!” Are you right now? What does the geology of nearby rock formations suggest? Is it likely there is gold in the creek? On the other hand, if you say “It’s not worth looking for gold here!”, then that is a perfectly fine and defensible value judgment. Scientists care a lot about that distinction, but not everyone else does.

How does this relate to our understanding of the effects of radiation? Much of our knowledge about the dose-response relationship of radiation exposure to disease has come from studies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors. As time has progressed, scientists have been able to gather more data and it has been possible to get statistically significant results for lower and lower doses of radiation. That is the equivalent of getting a bigger sieve when panning for gold. But still we do not have statistically significant findings below a certain level. Kugelmass interprets this as low doses having no effect. “There’s a practical threshold. In reality it doesn’t matter…. There is a net-zero effect on cancers at the end of the day.”

He searches for an analog. Background radiation in parts of Colorado is two to three times higher than elsewhere due to more uranium in the soil. “And yet we let people live in Colorado.” He then rails against the lack of “cost-benefit” analysis when it comes to nuclear energy. Lyman points out that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s standard is one of “reasonable assurance of adequate protection,” emphasizing that many of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s recommendations in the wake of Fukushima were rejected due to excessive cost.

As I listen to the podcast, I hear a host who is passionate about nuclear energy but without much depth of knowledge, finding the facts too complicated or too unintuitive to deal with and instead making appealing but misleading arguments. The two go on to talk about the Fukushima meltdown, which occurred after a massive earthquake-induced tsunami flooded the emergency generators that were cooling the reactor. Many died from the earthquake and tsunami and subsequent social upheaval, but relatively little injury has been attributed to radiation exposure. Kugelmass is incensed by this.

“To me, what Fukushima showed is that we went so far overboard in our safety measures to begin with…. There were zero deaths in this accident, after the largest tsunami the Earth has ever seen and the second largest earthquake in human history.” Lyman pushes back, saying we don’t yet know the extent of the damage. He estimates that “a thousand or more cancer deaths” will be attributed to the excess radiation over time, based on the science, while Kugelmass says “zero deaths”. There follows a Seussian exchange.

Lyman: “If people are exposed to ionizing radiation, there will be an effect…. Because of the level of exposure compared to background, you may not be able to see it, but it doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

Kugelmass: “It does mean it’s not there.”

Lyman: “No it doesn’t.”

Kugelmass: “Of course it does.”

Lyman: “That’s a fallacy.”

Kugelmass: “That’s not a fallacy, it’s logically consistent.”

Lyman: “It’s not logically consistent. If an effect can’t be detected in an epidemiological study, it doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

Kugelmass: “On a practical basis, it’s not there. On a practical basis.”

Then, after more discussion, Lyman asks Kugelmass to be more precise:

Kugelmass: “At the point where you cannot tease out excess deaths from background cancer deaths, that’s the threshold. That’s the practical threshold.”

Lyman: “I don’t agree, people are still being harmed. It’s just there isn’t enough statistical significance to detect that. But if there is a dose-response relationship, people are being harmed, and you can’t pretend that’s not occurring.”

Kugelmass: “Theoretically somebody is being harmed.”

Lyman: “Look, if you want the industry to thrive, I don’t think denying the harm is a useful or productive way to go.”

Kugelmass then goes on an aside to rail against the engineering requirements for nuclear reactors. “Why does a nuclear plant cost $10 billion for a 1 GW plant today instead of the $1 billion it takes to build a coal plant? It’s $9 billion worth of unnecessary safety equipment to save zero lives in case of an accident.” After a brief but futile exchange on the value of building codes, they return to arguing about how much radiation people were exposed to at Fukushima. Kugelmass again asserts that it was so low as to have had no effect.

Kugelmass: “Not only was it well characterized, it was orders of magnitude, orders of magnitude, lower than what you would need to have an adverse effect from radiation.”

Lyman: “How do you know that? Have you done a population survey? Have you studied the movements of evacuees compared to the plume contamination, to ground contamination? You are saying ridiculous things. If you want to establish credibility, you can’t just dismiss the established basis for how you understand and study these issues.”

Lyman tries again when Kugelmass conflates whether the harm exists with whether the harm matters. “First you said it wasn’t going to affect anyone if it was below a certain dose, and now you’re saying from a cost-benefit it doesn’t matter. Those are different things. I accept if you say it doesn’t matter, that’s fine.” Kugelmass talks over him: “I say both of them! I say both of them!”

The podcast wraps up with this exchange:

Lyman: “Look, if you want to make a technically valid argument, then you have to provide references that support it. I haven’t heard anything…. Write a paper, have references, submit it for peer review. You have your opinions, but they’re worth nothing Bret. Sorry.”

Kugelmass (laughing): “That’s funny. That is the de facto argument whenever somebody feels like they’ve been outgunned, they say ‘Go write a paper.’”

Lyman: “I’m not outgunned. I’m not going to accept your assertions about stuff that you obviously have no basis for.”

So, what is my point here? I found this discussion truly awful. I have little tolerance for the intellectual hubris that Kugelmass displayed, coupled with his impatience with science and his unwillingness or inability to communicate precisely. Lyman displayed considerable forbearance in my book; it was all I could do to not turn the whole podcast off. But with similar conversations happening in so many places, with people deriding science while wielding megaphones, scientists have got to find a way to bridge the gap. Can we work out how to talk more intuitively about probabilities and risk? Can we acknowledge the urgency around climate change and find ways to address those who want to see more speed?

I had a chance to speak with Dr. Lyman about his thoughts on this. While he pointed to some efforts to streamline nuclear energy development, like the recent Nuclear Energy Innovation Modernization Act, he feels that this direction is misguided. “The real problem is not safety regulations, it’s the industry’s inability to build on time and on budget.” He points to recent studies by MIT showing that these problems largely stem from issues with planning and construction, such as incomplete designs, inflexible construction practices, unreliable supply chains, and inadequate expertise. “They can’t raise enough capital, so they are turning around and scapegoating others instead.”

Moreover, he emphasizes that cutting corners on safety can be counterproductive. “The legal authority of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is to protect public health and safety, but industry benefits from the regulations as well. When safety problems occur, it is bad for the industry.” He worries that financial pressure on the industry is pushing them to take shortcuts on safety.

I asked if he felt any technologies coming down the pike were particularly promising, and his response was a depressing “Not really.” As an example, he talked about the NuScale reactor, a next-generation small, modular reactor that is meant to be cheaper, safer, and more flexible than traditional reactors. It is designed to shut down and cool down automatically if the core overheats, with no need for power, water, or operator intervention. During the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s approval process, a significant flaw was found in the design, raising questions about whether the automatic safety mechanism would work. Yet the company had been so confident in their design that they requested a waiver of many of the other safety requirements, such as an emergency planning zone (the absence of which would make the reactors easier to site). Lyman thinks it is “penny wise and pound foolish” to forego proven safety mechanisms in the hope that a new technology will work flawlessly. “The industry needs to focus on the fundamentals, where the costs and delays are, rather than cutting corners on safety. There’s not much good to come from promising what’s too good to be true.”

I’ll end with this quote from Lyman from 2013, still very relevant today: “Nuclear power’s worst enemy may not be the anti-nuclear movement ... but rather nuclear power advocates whose rose-colored view of the technology helped create the attitude of complacency that made accidents like Fukushima possible. Nuclear power will only be successful through the vision of realists who acknowledge its problems and work hard to fix them.”

Notes and References

0. Interested in making some charitable donations to organizations that are addressing climate change? Or in purchasing offsets for your emissions last year (or this coming year)? Check out Giving Green, as recommended by Robinson Meyer of The Atlantic. “Giving Green advises people on how to fight climate change with their donations in the most evidence-based way possible.”

1. Cynthia Jones of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) provides an interesting overview of the history of the NRC’s radiation protection policies.

Current Climate Data (October 2020)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.