That seems like a weird question. We want to recycle, so why would we want smaller bins? Another way to think of the question is: Are we too good at recycling?

Most of us love to recycle. A recent survey of almost 3000 people across the West Coast found that more than 95% of residents recycle, with 92% saying it is important to them. Most are also happy with their recycling service. We certainly have great service here in the mid-Peninsula. Palo Alto takes a wide range of items in its blue bins and recycles every week. Mountain View, Menlo Park, and other cities offer simple, easy-to-use (single-bin, curb-side) recycling. We recycle because it’s good for the environment and we want to keep things out of the landfill. We compost for the same reason.

It works. A “significant majority” of studies have shown that recycling and composting are beneficial for the environment, conserving resources and reducing pollution. (1) For example, David Allaway, a senior policy analyst in Oregon’s Department of Environmental Science, reports that the EPA’s WARM tool shows that in 2016 Oregon’s recycling and composting reduced statewide emissions by about 5%.

So how can our bins be too big? There are a couple of separate issues.

Recycling (and composting) can cause us to ignore the bigger benefits of reducing and reusing.

In last week’s blog post, I wrote that plastic cups were considered okay to use at an event because “Well, they are recyclable.” My suggestion that we use paper cups wasn’t a whole lot better. Why not ask people to bring their own cups? Recycling can distract us from reducing our use of disposables.

Composting can be similarly distracting. Allaway reports on a very successful food-waste reduction initiative at Oregon State University. Food waste in a dining hall was reduced by more than 70% with clear messaging. But when composting was introduced, food waste went right back to where it had been. Composting somehow made the food waste okay.

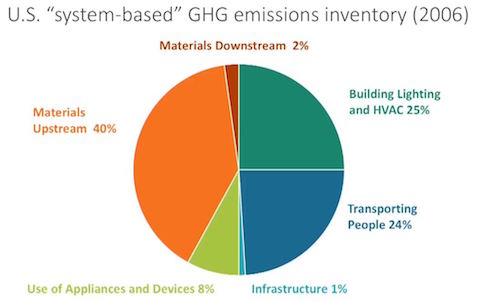

While composting and recycling do help to reduce emissions, the vast majority of emissions come from the production and transportation of goods before they ever get to the consumer. This chart from a presentation by Allaway shows that “upstream” emissions are about 20x the post-consumption or “downstream” emissions.

Upstream emissions for materials are 20x the post-consumer emissions. (Source: 2018 David Allaway presentation)

Even with near-perfect recycling of materials, the overall contribution of materials in this inventory would be 38% instead of 40%. While these numbers may have been considerably refined since this 2006 analysis, it’s clear that reducing and reusing materials has a much greater impact than recycling them does.

Our capacious recycling bins are distracting us from a more important goal.

Aspirational recycling adds cost and may worsen pollution.

We love to recycle, so much so that we have a tendency to optimistically recycle things. That may be because we don’t know what is allowed or because we figure the recycling service will sort it out anyway. Either way, these micro-decisions are costly. The facilities end up needing more sophisticated sorting services, taking them down more to untangle unexpected items from machinery, and dealing with lost revenue due to contaminants they are unable to remove.

Contamination is a big problem. It’s partly the result of complex and inconsistent rules for recycling. For example, sometimes #1 and #2 are considered to be recyclable plastics, but sometimes not. Mountain View, for example, does not allow so-called thermoform plastics like clamshells to be recycled, even if made from #1 plastic, while Palo Alto allows virtually everything, even film plastics if they are bagged.

Thermoform plastics are not often recyclable, regardless of the type of plastic they are made from.

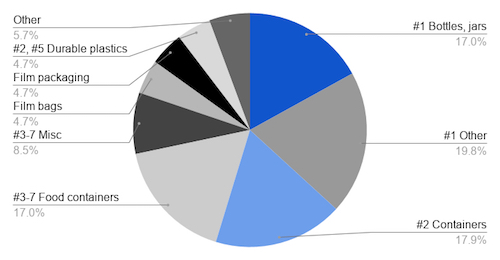

As a result, Palo Altans are probably “aspirational recyclers” everywhere they go because of their home habits. But Mountain View residents also struggle. According to Mountain View’s 2019 Materials Waste Characterization study, only 35% of the plastics in the blue bins are actually recyclable. Sure, some of that may be visiting Palo Altans, but the rest? Mountain View residents and visitors don’t seem to know that these rigid plastics, film plastics, and more are not recyclable in their city. (And just for the record, carpeting and ice packs shouldn’t be in there either!)

Only 35% of the plastics in Mountain View’s recycling bins are recyclable (those are shown in blue). (Source: 2019 Materials Waste Characterization study)

It’s not only we residents who are aspirational when it comes to recycling. Our waste processors may be as well. Recycling works best when there are verifiable and ideally domestic markets for the materials. (2) But cities may aggressively pursue other markets because residents want to recycle more. These markets are not especially stable. As the price of oil has dropped, virgin plastic has gotten relatively cheaper. If a market in Asia dries up because it can no longer compete with new materials or because they have a surplus of recycled material, chances are suddenly much higher that your “recycled” plastic will end up in the ocean than if it had bypassed recycling and gone straight to a landfill in the US.

Our optimistic approach to filling our large bins is adding cost and may be worsening pollution.

Recyclable products are not always the lowest-impact.

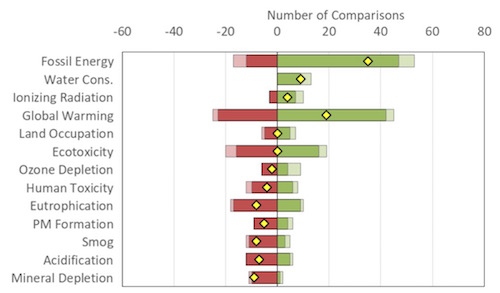

If we focus on “recyclability” too much when we do need to buy things, we may be choosing a higher-impact option overall. I started buying tuna pouches instead of tuna cans about a year ago after I read this article on the lifecycle emissions of each. The chart below shows that in a good number of comparisons found in the scientific literature, “recyclable” packaging has a greater overall environmental impact (those are shown in red).

Recyclable packaging and containers are not always better for the environment than non-compostable (Source: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality)

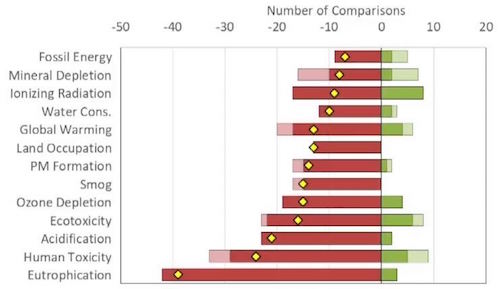

The situation is even starker for compostable utensils. Nearly all of the comparisons show they use more resources and have greater impact over their lifecycle than non-compostable utensils.

Compostable foodware is generally worse for the environment than non-compostable (Source: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality)

Plastic straws are another interesting one. If you choose to use a steel, glass, or even bamboo straw, you need to be prepared to use it (and not lose it) 50 or even 100+ times.

This may not be news to many of you. But how are we supposed to intuit lifecycle emissions? There is no easy way to know which products have lower-impact life cycles than others. As a result, even though we know that the marketing is often deceptive, we go with “recyclable” or “compostable” because it’s all we’ve got.

Our roomy recycling bin encourages us to opt for “recyclable” items, which may be the worse choice.

Is there a better option?

A large, low-cost recycling bin is an invitation to recycle. You may have heard of capacity-induced demand. When we add lanes to highways, we get more traffic. When our recycle bin is big and cheap, we don’t think twice about putting things in it. We certainly prefer it to our more expensive and perhaps smaller trash can. This roomy, inexpensive option can lead us to forget about reducing and reusing, to recycle “optimistically”, and to disregard lifecycle impacts.

If we have less room to recycle, we might push back more on waste. Have you bought something recently that was packaged with styrofoam pieces for protection? Or have you opened a box to a flood of styrofoam peanuts? It’s a nuisance because there is nowhere to put the stuff. As a result, you try to avoid styrofoam when possible, and may even prefer shippers that don’t use it. A smaller recycling bin could work the same way. Instead of looking for recyclable items, we might instead look for options that create less waste overall.

In that vein, I also wonder if Palo Alto should accept fewer types of recycling. It seems like a downgrade. But if Palo Alto were to stick with “bottles, jars, jugs, and tubs”, it might reduce confusion and mistakes, lower costs, and encourage better consumption behavior. Palo Altans do not like to throw things in the trash!

The reality…

Many of us are busy people, especially right now. Accurately comparing the lifecycle emissions of what we are buying is way beyond us. How long do you really want to stand in the yogurt aisle debating between a plastic or a glass container?

Your guess is as good as mine…

Furthermore, opting not to buy disposable items is a problem if that is all we are offered.

We can’t be expected to analyze our purchases and our trash so much. “Just sell me the right thing and I’ll buy it,” you may be thinking. I am, anyway. I would love for the manufacturers to be building things to last, making them easy to repair or refill, reducing packaging, and generally designing for low-impact.

In the meantime, we can keep our focus on reducing and reusing, and use our purchasing power to nudge vendors in that direction. We aren’t going to compost and recycle our way out of our environmental impact.

Palo Alto is going to roll out a campaign soon to nudge us in the direction of generating less waste. I hope we can have some good discussions on what’s working and what’s not.

Notes and References

1. This and much other information in this blog is from a 2018 talk by David Allaway, a senior policy analyst in Oregon’s Department of Environmental Science.

2. When recycling is done in places like Asia, there is a much greater likelihood that non-recyclables in the mix will end up in the ocean. It is also harder to verify recycling when it’s done at a distance.

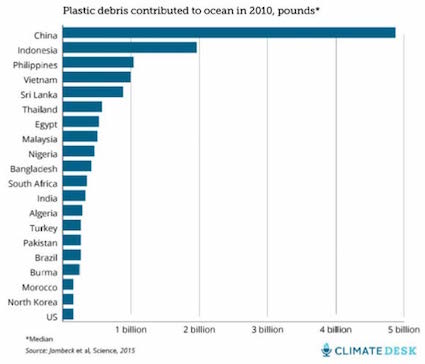

Much more plastic ends up in the ocean from Asia and Africa than from the US.

3. This is a good overview of what the plastic numbers mean.

4. You can read some about the economics of recycling in the Sacramento Bee (2019). The numbers have gotten much worse as we’ve moved to a single bin and added many more types of materials. Sorting costs have gone up and the value of the resulting materials have gone down due to contamination. I hope to do a subsequent post on this topic.

Current Climate Data (July/August 2020)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.