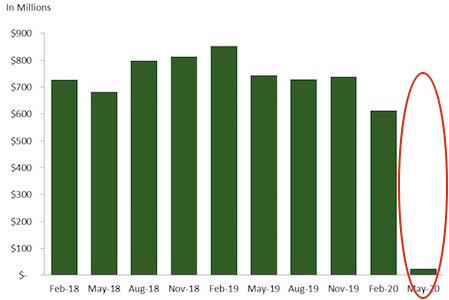

California’s cap-and-trade revenue disappeared in the May 2020 auction (Source: Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2020)

You may be thinking, “Well, coronavirus, who could have anticipated that?” But the impact of coronavirus on emissions is arguably much too small to trigger this lack of demand. In fact, this kind of sell-off happened in pandemic-free 2016.

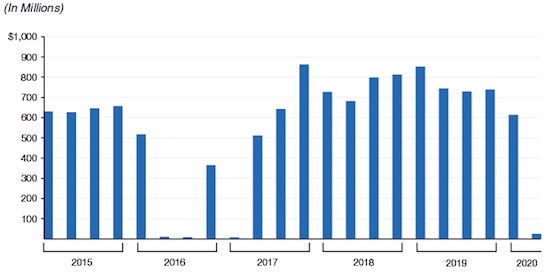

California’s cap-and-trade revenue has proven volatile (Source: Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2020)

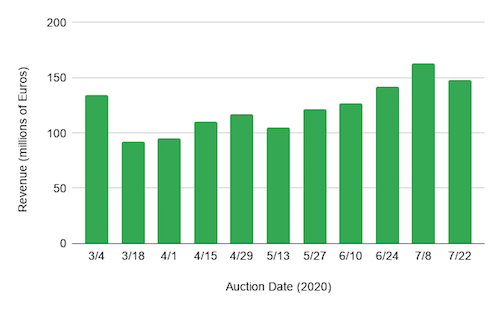

Furthermore, while the East Coast and Europe also experienced the pandemic, their cap-and-trade systems did not take this kind of hit.

Europe’s cap-and-trade revenue has been much more stable during the pandemic (Source: Intercontinental Exchange, 2020)

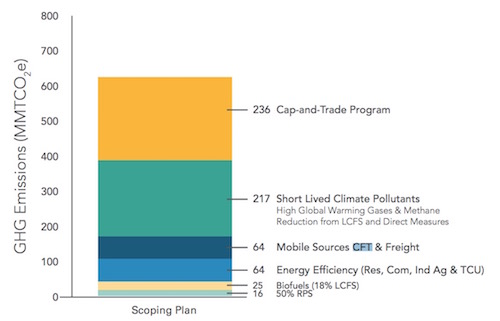

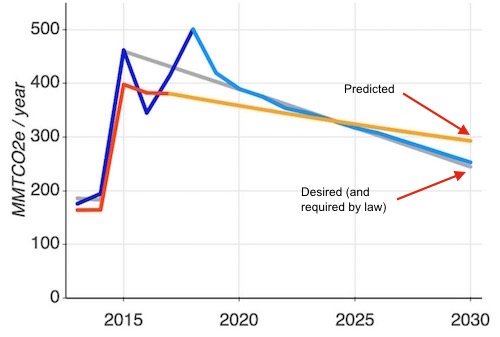

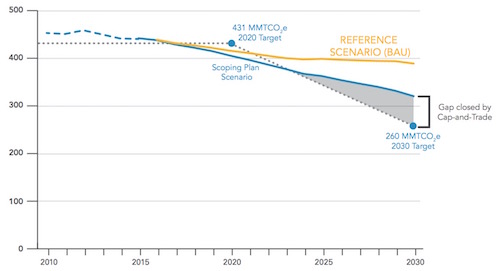

And yet California is increasingly relying on cap-and-trade to reduce emissions. You can see in the chart below that California believes that more than one-third of its emissions reductions by 2030 will come from cap-and-trade.

Projected sources of emissions reductions 2021-2030 (Source: CARB, 2017)

Cap-and-trade is not set up to do that. I want to explain what the basic problem is with cap-and-trade, and what we can do to address it.

Too much too soon

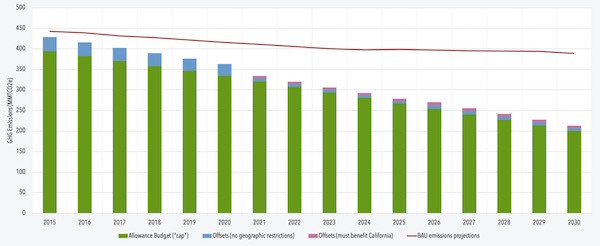

Cap-and-trade works by setting a series of decreasing emissions caps for each year.

California’s decreasing emissions caps through 2030 (Source: C2ES, 2019)

Participants are required to get a permit (“allowance”) for each ton of CO2 that they emit, and the state only sells a certain number of those permits. (1) The price is bounded by a floor (currently around $17) and a ceiling (currently around $60), which gradually go up each year, and the allowances are auctioned every three months. There is also a “secondary market” where organizations (and investors) buy and sell allowances in between auctions. (2) The sensible idea behind cap-and-trade is that the state sets the emissions target and the market figures out the most cost-effective way to achieve it.

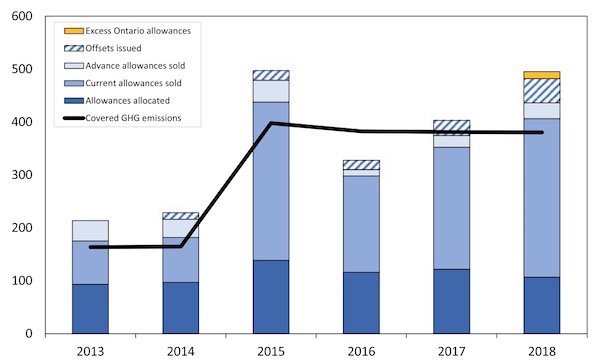

Pretty simple. But how has it worked in practice? Well, emissions quickly fell below the caps due to effective regulations like our renewable portfolio standards and low-carbon fuel standards. Because of that, the price of allowances stayed low and emitters were able to purchase more than they needed. The allowances don’t expire or lose value, so they can be used to offset emissions in the future. This excess of supply happened every year except 2016. (2019 is not shown but it is expected that allowance purchases then will also exceed emissions by a good amount.) (3)

Emissions (navy line) are below allowances for every year but 2016 (Source: Cullenward, Inman, and Mastrandea, 2020)

What happened in 2016

In 2016 emitters began to question whether cap-and-trade would be extended past 2020. This pushed down the price of allowances, so banked (saved) allowances became cheaper than the auction’s floor price. This lasted for several auctions, depressing auction sales as shown in the second chart in this post. It wasn’t until cap-and-trade was extended in early 2017 that emitters once again invested in allowances. Since most of the unsold allowances from 2016 were still valid (they can be auctioned for up to 24 months after they are first made available), the auction supply was ample and prices were low, so allowance sales quickly rebounded.

Because of the generous supply of allowances, the auction price has rarely risen above the floor, as you can see in this chart. The green triangles mark quarterly auction prices, the light grey line represents the “floor” price, and the blue line represents the price on the secondary market. Whenever the secondary market goes below that “floor” price, as it did in 2016-17 and again a few months ago, auction revenue plummets.

Cap-and-trade allowance prices (Source: CARB, 2020)

Did a hedge fund just steal your EV rebate?

And that brings us to what happened in the May auction. Some time in March/April, the secondary market price tanked when a hedge fund sold a whole lot of allowances. And of course the pandemic suppressed demand some. The low prices in the secondary market meant that few allowances were bought at auction, and revenue dropped from around $700 million to around $25 million. The clean-energy programs that relied on this auction revenue have had to make significant cuts, with CARB’s budget for low-carbon transportation reduced by over $80 million (out of $557 million). Some of that money was likely designated for EV rebates.

So, did a hedge fund trader steal your EV rebate? Or maybe the coronavirus? Much as we would like to blame them, they aren’t the real problem. As Stanford economist Danny Cullenward says, “The fact is that hedge fund margin calls and macroeconomic shocks wouldn't crash a market if it were well-designed.”

What is wrong with California’s cap-and-trade program?

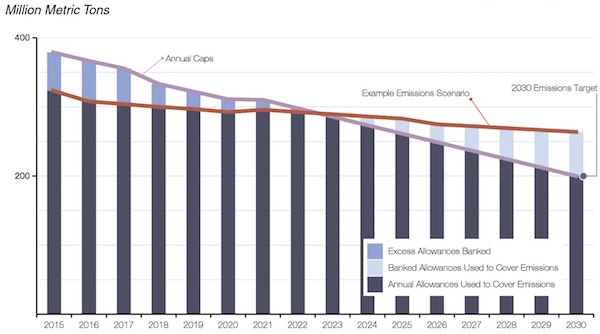

The real problem with California’s cap-and-trade program is that far too many allowances have been set aside (“banked”) to offset future emissions. Since emissions were well below the caps in the beginning, allowances piled up and now emissions can be well above caps but still in compliance in the future. This diagram shows in general what that looks like.

The banking of allowances means emissions can exceed caps in the future (Source: Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2017)

In fact, Cullenward’s team at Net Zero has modeled the banking of allowances and predicted, using many of California’s own assumptions, that we will be considerably over the cap in 2030.

We are projected to hit 293 MMTCO2e in 2030 (the orange line) rather than 245 (the grey line). (Source: Inman, Mastrandea, and Cullenward, 2020)

Is that so bad?

Some of you may be wondering, is that so bad? Isn’t it a “good problem to have” that emissions went down so fast early on? And aren’t the total reductions the same either way? Some policy folks, including Harvard economist Robert Stavins, will say that since carbon dioxide emissions are a “stock” problem (it’s only the aggregate amount in the atmosphere that really matters), it doesn’t matter if the emissions reductions come earlier or later.

I strongly disagree with that. It’s not just because CARB is statutorily required to hit the 2030 benchmark, though of course that matters. And it’s not just because the oversupply makes revenue so unpredictable. It’s also that I think trajectory is important since reducing emissions only gets harder from here. We need to keep the pedal to the metal on emission reductions as we move towards 2030, not hit cruise control by relying on banked allocations. In Europe, when they noticed that they were banking too many allocations, they reduced the caps while also postponing the auction of a good number of allowances. On the east coast, they automatically withhold allowances when the auction price falls too low. But California’s cap-and-trade has no such corrections. Instead, it is designed to be a backstop to emission-reducing regulations, and to hit a minimum aggregate (“stock”) reduction in emissions rather than a specific 2030 benchmark. Yet now the program is being called upon for over one-third of the reductions needed to hit our 2030 target.

So what can we do about it?

I am no economist, but from what I can tell there are plenty of ways to shore up our cap-and-trade program. As other exchanges do, we could automatically adjust the number of allowances for auction depending on how many are available on the secondary market, the state of the economy, and other macro-economic factors. We could adjust the price floor and/or the emissions caps. We could have allowances expire some time after they are purchased, or at least discount them. We could also have unsold allowances expire earlier. There are various reserve buckets of allowances that we could reduce in size, increase in price, or both.

Instead, fossil fuel companies have pushed California to be even more generous with allowances, and we now have an infinite number at the ceiling price, and extra allowances at specific lower prices so that prices don’t go up too fast. They are also pushing for a lower ceiling price, with no interest in matching the real-world cost of removing emissions from the atmosphere, or matching the “social cost” of carbon. They just want a low ceiling.

The difficulty with cap-and-trade is not that it is a hard problem to fix. There are plenty of ways to tweak it to give us a better chance at hitting our 2030 goal. Instead, the problem seems to be a political one. When State Senator Bob Wieckowski of Fremont sponsored a bill to spend $200,000 to evaluate the cap-and-trade design, the manufacturing lobby spent $900,000 to produce this ad to successfully fight the budget item. But a few years later, now that auction revenue has disappeared again, CARB is finally considering taking another look at the program. Hopefully they will.

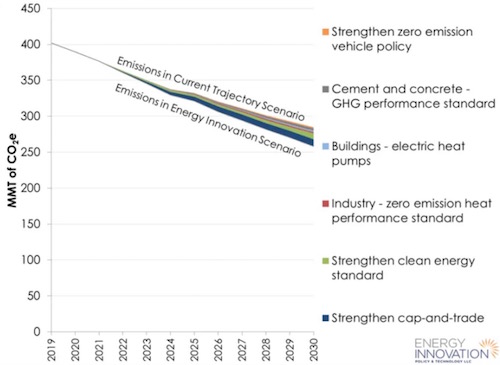

In the meantime, we need to think hard about the next set of sector-specific regulations that will help us reduce our emissions. Energy Innovation has suggested a combined approach of fixing cap-and-trade, strengthening some existing standards, and focusing on new areas like building heat and cement.

Policies to help us achieve our 2030 emissions goal (Source: Energy Innovation, 2020)

We don’t know for sure what will work, but we have options. What we do know is that CARB’s 2017 Scoping Plan is magical thinking.

We are asking too much of our faulty cap-and-trade system (Source: CARB, 2017)

I look forward to hearing your thoughts on cap-and-trade or carbon pricing more generally, and how you think we can hit our 2030 goal. Chris Rapley, Professor of Climate Science at University College London, once said "Nature is our life support system. If you were in the Space Station and one of the astronauts started to try and break the oxygen supply, you would try and stop them; you would not try to tax them, you would stop them.” You can see where he is coming from.

Notes and References

0. Thank you to Stanford economist Danny Cullenward for his input on this blog post.

1. The state provides these at no cost to many organizations, but sells them to others.

2. There are many more aspects to the design of cap-and-trade. For example, the state provides “reserves” of allowances to use at different points if prices get too high. California also allows emitters to buy a limited number of emissions offsets instead of allowances.

3. The generous caps seem to have been by design. This study found that “California’s emissions cap for 2013-2020 was set at a level that implied a 94.3 percent probability the allowance market would clear at the price floor, with total emissions below the cap. We find a 1.1 percent probability that the price would be in the interior equilibrium range, above the price floor and below the market’s soft price ceiling at which some additional allowances are released, described further below. The remaining 4.6 percent probability weight is on outcomes in which the price is at or above the soft price ceiling.”

4. This report from the Legislative Analyst’s office has a nice summary of cap-and-trade followed by some of the design problems. Stanford economist Danny Cullenward also has a great Twitter thread linking to many good write ups on this topic.

Current Climate Data (June 2020)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.