A month ago I was watching a video from the Stanford Global Energy Forum and was struck by an audience survey done at the beginning. The question posed was as follows:

In a (pre-pandemic) “business-as-usual” scenario, how many years do we have left before the world exceeds the CO2 emissions budget to keep the global average temperature rise below 2C with a 50% probability? (1)

1. Less than 10 years

2. 10-20 years

3. 20-30 years

4. More than 30 years

Think about your answer before continuing.

The audience response was:

51% Less than 10 years

32% 10-20 years

16% 20-30 years

1% More than 30 years

The moderator revealed the answer as 20-30 years. (2) 83% of the audience thought we had less time, with half the audience thinking we had much less time. In a way this is a trick question. The question is more often posed with 1.5C as the target, at least recently, in which case the answer is indeed around 11 years. But still, the responses were illustrative to me.

Global warming is a serious problem requiring large-scale change in the way we do things. It is important to understand the timeframes we have so that we can plan accordingly. What struck me here was not that the audience was off on the answer. I think that was expected. What I appreciated was that the moderators asked this particular question, presumably to make the point that details matter and we can and should do better than reflexively thinking “This is an emergency, there’s no time left!”

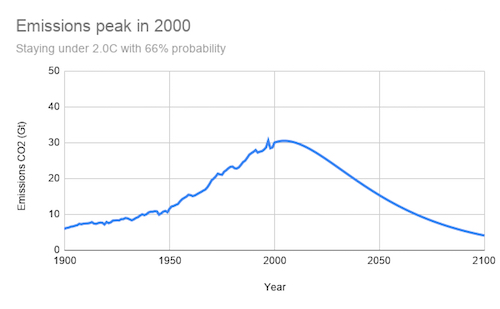

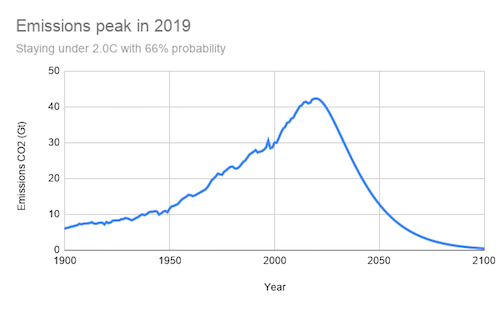

To be clear, delay hurts. The longer we take to address climate change, the more risk we incur and the more our likely costs go up, both economically and socially. Take a look at the two curves below. The area under the curves is the same, which means that the same amount of CO2 is emitted in each case. It is the largest amount we can emit while likely limiting temperature rise to 2C.

If we had begun reducing our emissions in earnest in 2000, we would be needing to reduce emissions at about 2% per year to hit that target, assuming no negative emissions. That is doable, though not easy.

This curve slopes down at 2% each year 2020–2050 (Source: CICERO)

But if we start now, only twenty years later, we would need to reduce emissions at a rate of 4%, which is much more difficult. (3)

This curve slopes down at 4% each year 2020–2050 (Source: CICERO)

Each year we delay, emissions accumulate, temperatures increase, the problem we need to solve gets harder and more expensive to address, and our reliance on negative emissions grows, though we have no technology to achieve those at scale.

We need to get moving. But what is the best way to spur action sooner rather than later? Are deadlines like “We have X years left” an effective rallying cry? Do they encourage progress by alerting more people to the need to act now? Or do they impede progress by damaging credibility as deadlines come and go without observable disaster, as they have been doing?

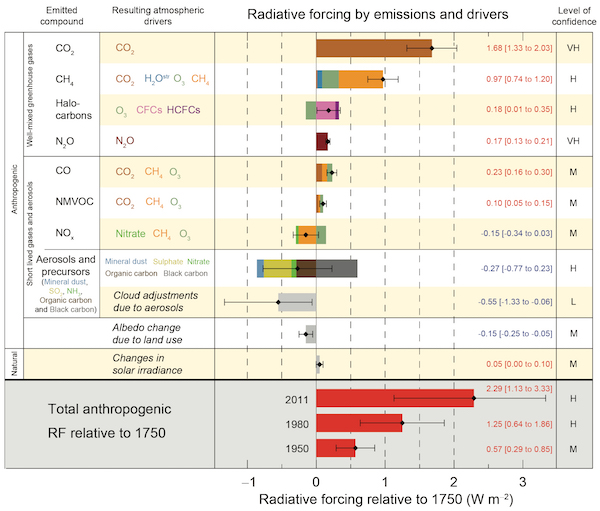

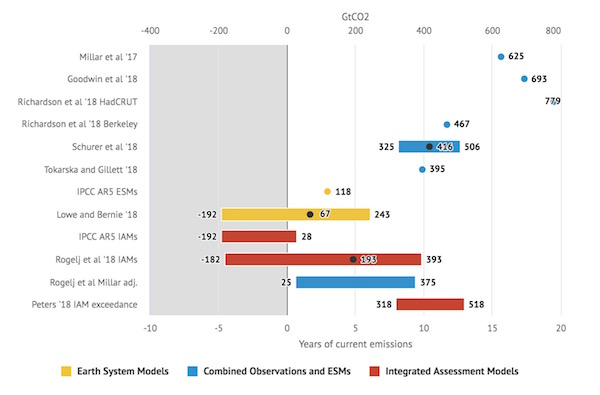

One problem with many of the climate deadlines we hear is that both specificity and uncertainty are omitted from the sound bites. You have heard people say “We only have twelve (eleven) years left.” Some of you may have asked “Until what?” (That is the lack of specificity.) But even more is left unsaid. That particular 12-year deadline is derived from a recent IPCC report. You can find what the IPCC actually says about the 1.5C deadline in footnote (4). The authors are pretty confident about how fast we are emitting CO2, but they are much less sure about our carbon budget—how much we can emit to stay under 1.5C. So they give a wide range of estimates. The sources of uncertainty include how much of a role Earth’s feedback processes will play (e.g., melting permafrost and wetland emissions), how much of a cooling effect aerosols (e.g., from pollution) are having and will have, and the role methane will play. You can get a sense of the uncertainty in this diagram from CarbonBrief, which shows estimates of how much CO2 we can emit to have a two-thirds chance of staying below 1.5C. It’s possible we have already passed the deadline or it may be almost 20 years in the future.

Range of carbon budget estimates to stay below 1.5C with two-thirds probability (Source: CarbonBrief)

This is why the IPCC says it has only “medium confidence” in its estimate of 420 Gt CO2 for this target. And even so, all of this skirts the issue of whether we might prefer to consider a 50-50 chance of success rather than a two-thirds chance, which would give us additional years. At the end of the day, does it really matter? Would it change what we would do?

Rallying cries like “We have only twelve years left” are over-simplified to the point of being meaningless (“until what?”). They incorporate false precision (“twelve but not thirteen?”). And the lack of an immediately obvious consequence when we fail to hit them damages credibility (“crying wolf again?”).

One of the coordinating lead authors of a relevant chapter in the IPCC report, Myles Allen, comes out a hard “no” on deadlines of this form. “I appreciate that headlines have to be snappy, but they also have to be true, and effective. And ‘the world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change’ is neither.” He argues that we should focus instead on the cleanup costs we are incurring (negative emissions) as we delay, which he estimates at today’s rate to be around $250,000 per second. “Surely if we have been trying the same (planetary emergency) message for 20 years with almost no success it is worth trying some alternatives?” He urges “Please stop saying something globally bad is going to happen in 2030. Bad stuff is already happening and every half a degree of warming matters, but the IPCC does not draw a “planetary boundary” at 1.5C beyond which lie climate dragons.”

Environmental social scientist Shinichiro Asayama and others writing last year in Nature Climate Change worry about the effect of these sound-bite goals. They caution that a narrow focus on hitting a number can lead to the neglect of long-term costs and values like justice and sustainability. They also argue that deadline-oriented messages can be alarming and even polarizing, “restricting the possibility for crafting enduring bipartisan solutions”. An environmental policy researcher from UCLA, Jesse Reynolds, points to the credibility hit of missed deadlines and notes that the inevitable moving of the goalposts afterwards can be deflating and self-defeating. (5)

We have delayed meaningful climate action for decades. The time to act was yesterday. But it is also today, and it will be tomorrow. The problem only gets worse the longer we wait. How do we get people to understand that even though deadlines have come and gone, the urgency has only increased? As Myles Allen suggests, it may be time to nix the deadlines and try a different approach. Cost seems like a good one, and the financial industry is coming around to that. I will talk more about the costs of climate change in some future blog posts.

In the meantime, how much time do we have left? The question is not well specified, but it is useful to know that the IPCC asserts with high confidence that emissions need to be about 45% of 2010 levels by 2030, and zero’d out around 2050, to stay below 1.5C. (6) These are very difficult goals to achieve. So my answer would be “It’s never too late, but sooner is better. There’s no time like the present!”

Notes and References

0. Thank you to my daughter Emma for her artwork.

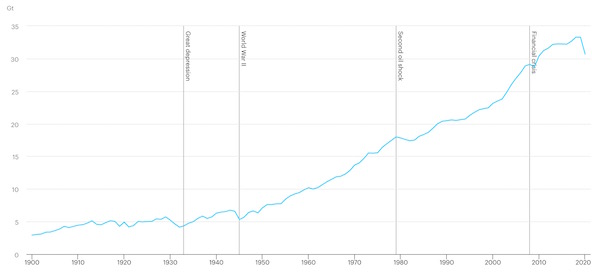

1. Not sure you understand the question? As you may remember from these two blog posts, when we add insulation (greenhouse gases) to our planet, we create an energy imbalance: more energy comes into our ecosystem than leaves it. The temperature of the planet rises until reaching a new equilibrium that balances energy-in and energy-out. Scientists have studied this and can estimate how much more CO2 we can emit while still staying below a certain temperature. They then translate that into a time period (“How much time do we have left?”) by dividing by the rate at which we are emitting CO2.

2. FWIW, I’m not entirely sure that is the correct answer. The answer given aligns with this graphic from 2017. But carbon budget estimates have gotten more generous lately and the newer IPCC report says in Table 2.2 that the remaining carbon budget for this scenario is 1500 Gt CO2, which maps to 36 years based on the rate we are emitting it (42 Gt CO2/year from that same report). Even if you subtract a few years to account for the budget’s starting year of 2018, that still gives the answer as (d). Either way, the overall point being made is the same.

3. For perspective, the International Energy Agency expects emissions to drop about 8% this year, during which global changes in behavior led to precipitous drops in travel, economic activity, and energy use.

4. Section C.1.3 of the report summary enumerates both how much CO2 we can emit to stay “within budget (around 420 Gt for a 66% chance or 580 Gt for a 50% chance of staying below 1.5C), and how fast we are emitting CO2 (around 42 Gt per year), along with the sizable uncertainties associated with those estimates. Here is the relevant text: “The associated remaining budget is being depleted by current emissions of 42 ± 3 GtCO2 per year (high confidence). The choice of the measure of global temperature affects the estimated remaining carbon budget. Using global mean surface air temperature, as in AR5, gives an estimate of the remaining carbon budget of 580 GtCO2 for a 50% probability of limiting warming to 1.5°C, and 420 GtCO2 for a 66% probability (medium confidence). Alternatively, using GMST gives estimates of 770 and 570 GtCO2, for 50% and 66% probabilities, respectively (medium confidence). Uncertainties in the size of these estimated remaining carbon budgets are substantial and depend on several factors. Uncertainties in the climate response to CO2 and non-CO2 emissions contribute ±400 GtCO2 and the level of historic warming contributes ±250 GtCO2 (medium confidence). Potential additional CO2 release from future permafrost thawing and methane release from wetlands would reduce budgets by up to 100 GtCO2 over the course of this century and more thereafter (medium confidence). In addition, the level of non-CO2 mitigation in the future could alter the remaining carbon budget by 250 GtCO2 in either direction (medium confidence).” Article 2.2 has more detail.

5. Jesse Reynolds gives an example of a 3-year deadline posited three years ago by some climate leaders, then shows how we haven’t met it (“According to the latest data that I found, none of their specific criteria have been achieved, many fall dramatically short, and none are on track to be met.”), and asks “So what?” It’s a good read.

6. See section C.1 of the report summary.

7. InsideClimate News has an easy-to-read overview of carbon budgets.

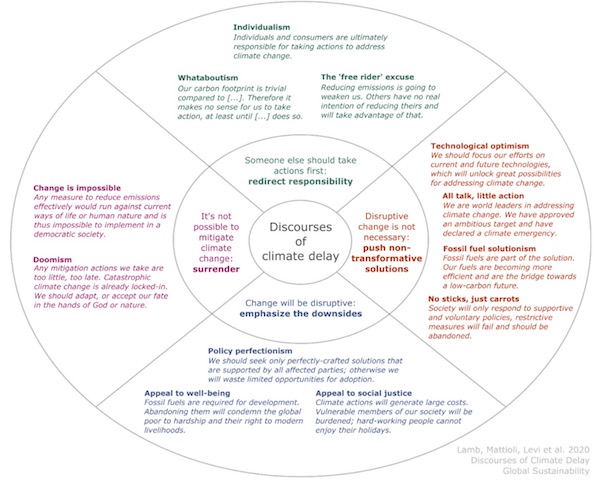

8. Tangentially related, CarbonBrief just published a summary of work by social scientists that categorizes rationales that have the effect of delaying action on climate, along with some real-life quotes exemplifying these types of arguments. It’s worth a read, as I’m sure you will recognize many of these types of commentaries. Here is a diagram from it, in case it’s readable for you in our 600-pixel-maximum format...

Current Climate Data (May/June 2020)

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.