Here is a fictitious example that illustrates some of the problems with carbon offsets.

China is working hard to reduce the country’s emissions, cleaning up and (over time) shutting down coal plants, planting billions of trees, operating the largest electric bus fleet in the world, and so on. But the emissions reductions are not happening fast enough to meet their goals. They search around the world for where they can do more to help. They are very enthusiastic about biking so they look for places where more cyclists would make sense, settling on the Bay Area as a terrific example with its flat terrain and temperate weather. They donate 50,000 quality commuter bikes to a local organization to give away, and then offset the emissions for 50,000 average car commuters. Success?

Not exactly. How are the local distributors going to find people who want to bike? Many will just take the bikes and resell them. Other bikes will rust in backyards after a few attempts to commute, or after a rainy winter dampens any cycling enthusiasm. The local distributors try to verify that the people who took the bikes are using them to get to work, but they just hear over and over again that lives are too busy and jobs are too far away.

So the well-intentioned folks from China come back and observe that a key problem is that there is too little local retail in our area. They offer job training to help people switch from distant tech jobs to local retail jobs, providing a nice benefit for the residents (local retail!) as well as a big reduction in emissions because more people can now walk or bike to work and shopping. Success?

Ha. Tech pays a lot more than local retail, to start with, so it’s hard to recruit people. A few people do attend the job training, but they don’t have the skills to make a go of local retail, which is a tough market.

At this point, the Chinese give up on bikes and consider trees. Everyone loves trees. They learn that, in some places, Americans have cut down trees and shrunk parks to make room for new development. So they find a tree-focused local organization in the Bay Area, Canopy, and give them money to preserve all the trees in the local parks. They then offset the emissions that those trees will capture for the next 50 years. Success?

Hardly. This “works” in the sense that the trees aren’t cut down for 50 years. But they weren’t going to be cut down anyway so the emissions weren’t really saved. The Chinese did not understand that our local government was already committed to preserving these trees. Yet Canopy was only too happy to take the money and credit the emissions.

This is kind of a silly example. These projects would be far too expensive to make sense in reality, and Canopy is not likely to be so complicit. But the point is, it is not easy to establish good carbon offset projects. A good project needs to make practical and economic sense for the locals, but it also needs to be something that wouldn’t have happened anyway. Offset projects that involve renewable energy, for example, are not valid if they make such good economic sense that they would happen soon even without the offset investment. Offset projects involving forest preservation won’t work if they make little economic sense for locals who would prefer to clear a field and engage in more lucrative farming. Even if locals are offered an alternative livelihood, such as harvesting and selling brazil nuts, they may not have the ability to develop a new market. There are numerous other problems with offsets. For example, trees may be saved in one place but then cut down in another place. This is referred to as “leakage” -- emissions are essentially exported to places with weaker governance. Offsets can even worsen pollution in some cases. For example, if a coal mine is receiving credits for flaring its leaked methane (1), those payments could prolong the life of the coal mine that might otherwise be unprofitable. This is referred to as a “perverse incentive” -- overall pollution is actually worsened by the offsets. (This particular criticism was one of several recently written up about California’s use of offsets in its cap-and-trade program.)

Even in the cases when an offset pencils out in practice, there may be concerns with appropriateness. Would it be better for China (in the above example) to work harder at cleaning up its own coal plants, rather than coming to the Bay Area to reduce emissions, even with good intentions?

Because of these many difficulties, the carbon exchange processes established during the Kyoto Protocol (the Clean Development Mechanism, or CDM) are widely considered to be a failure. According to a recent analysis, “It is likely that the large majority of the projects registered and (credits) issued under the CDM are not providing real, measurable and additional emission reductions.”

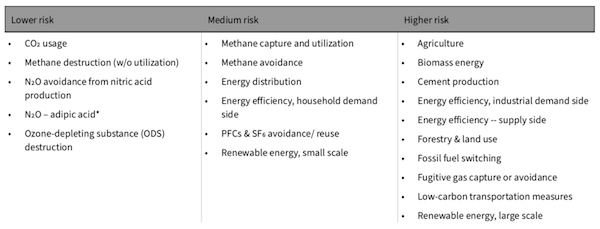

Fortunately, operators are learning from earlier mistakes. Reports have been written enumerating the risks and suggesting best practices for carbon offset projects. Below, for example, is a table from a Stockholm Environment Institute report itemizing the types of projects that are more likely to provide real, long-lasting emissions reductions.

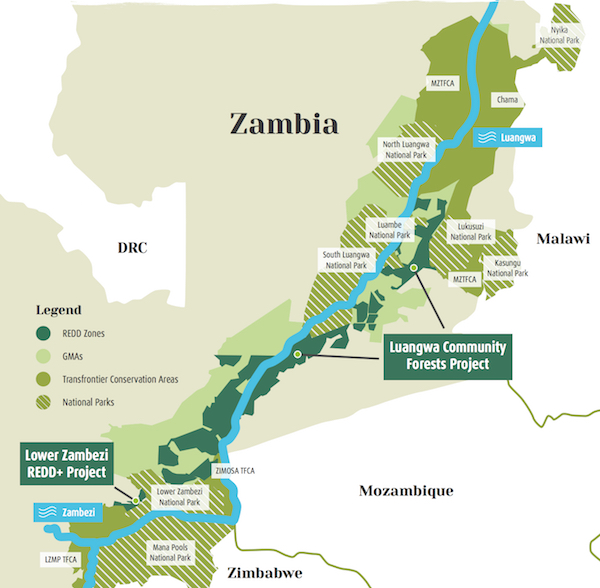

With attention to known problems, even the “higher risk” projects can be made to work. Zambia-based Biocarbon Partners (BCP) has been working hand in hand with rural communities for almost ten years to develop long-term forest conservation projects that improve the quality of life for locals while preserving habitat for endangered wildlife. (2) They are aiming to protect over 3800 square miles of critical wildlife corridor adjacent to national parks.

Biocarbon Partners protects the areas shown in dark green

I spoke with Gina Woolley, their REDD+ Technical Officer. “Rather than just treating the symptom, we look at the root cause of the forest degradation. Forests are cleared out for agriculture and for charcoal. There is a lot of poverty in these rural areas of Zambia. Villagers hunt wildlife for bush meat or to sell (for example, the endangered pangolin). This threatens trees and wildlife. So we partner with communities, we invest in people, to create long-lasting forest preservation.” BCP invests in education to raise awareness about ecology and sustainability. Training in conservation farming and an innovative “eco-charcoal” initiative reduce the need for clearing trees while also providing jobs. Bee-keeping and scouting/patrol provide more opportunities. Revenue from the offsets is also used for clean water (boreholes), agricultural tools like a hammer mill, buildings for schools and clinics, and more. BCP has created a program that works for the people, the wildlife, and the trees, while meeting the strict standards of carbon offsetting.

One of the keys to making this work is the local emphasis. “We are majority African-citizen owned and our team is 98% comprised of African-born staff. Our headquarters is in rural Zambia, amongst the communities and forests where we work; not in a capital city.” Their strategy to put the people front and center -- their mission is to “Make conservation of wildlife habitat valuable to people.” -- is another key ingredient to their success. As a result, BCP has attained top-notch verification of their offsets for many years running, and wildlife is beginning to return to some areas.

But how is a consumer to know if a project is good quality? Standards are evolving to better describe the qualities of the projects, and vendors are making it easier for buyers to find projects that are a good fit. I will talk more about standards and vendors towards the end of this post, but first I want to talk about pricing, which is pretty confusing.

Suppose you are interested in offering families who are cooking with coal or wood over an open fire the option of a cookstove that is healthier, faster, and cleaner. This cookstove project in Uganda costs $4.94 per tonne of carbon saved; this one in Malawi costs $8.50 per tonne, and this one in Peru costs $15.00 per tonne. Is the Peru project better? Not necessarily.

A variety of factors affect the price of a carbon offset, not just the type and location of the project. The Gold Standard has published a good overview of factors that affect offset pricing. For example, projects that have more oversight can be more expensive, as they strive to meet more comprehensive certification standards. Some verifiers may take a profit. Smaller projects are generally more expensive, since the certification overhead is relatively higher. Credits for projects that happened a while ago may be cheaper. Costs can change even within a project as it develops. (3)

So a cheaper project may remove just as much carbon as a more expensive project. And yet the cheapest offset may not be the best fit. A consumer may pay more for certifications that offer more assurances. The Gold Standard is particularly well-respected, as is the combination of VCS and CCB certification. The well-regarded Climate Action Reserve and American Carbon Registry standards focus on projects in the US, which some US-based consumers may prefer. (4) The “co-benefits” of a project (those beyond reducing emissions) may be significant for consumers and so will fetch a higher price. For example, some may prefer projects that benefit women or children, or that are located in developing countries, or that preserve crucial wildlife habitat.

A local offset vendor, Marin-based Cool Effect, is working to make it easier for consumers to purchase high-quality offsets that match their interests. After the founders led an effort to design and distribute cleaner cookstoves to homes in Honduras, they recognized a need to help consumers find projects that meet the strictest standards for offsets while also providing meaningful community benefits. Marketing Manager Blake Lawrence said that of the thousands of projects Cool Effect has looked at, they have visited 150-200, and of those sponsored 15-20. With interest in their offsets skyrocketing, they are working quickly to add more projects. (5)

Cool Effect puts a premium on transparency and financial efficiency. It is a non-profit that gives over 90% of its income to the projects. Project descriptions list risks alongside benefits so that consumers understand the challenges. But most of all they focus on the quality of their projects. They look carefully at the methodology for assessing offsets. For example, when deploying new cookstoves in Uganda, if a family takes the new one but also hangs onto their old one, then the emission savings are not counted. Strong community benefits help ensure the projects will last. One of Lawrence’s favorite projects involves installing biodigesters in rural farms. The digesters convert farm waste into methane, which is then used to power lights and stoves in the village. The result is cleaner, faster, and cheaper cooking, free electricity, and even less-smelly animal stalls, all while reducing emissions and helping to preserve trees. “Digesters are a great tool,” enthuses Lawrence. “You see immediate impact, improving peoples’ lives.” A short video taken on site reflects this.

A biogas digester being built for a project sponsored by Cool Effect

Are we being marketed to? Absolutely. Do vendors choose projects that will best appeal to guilt-ridden carbon emitters like us? Of course -- they need money to make an impact. But does “feel good” imply it does not “do good”? Not at all. Biocarbon Partners and Cool Effect, and others like them, are putting in a lot of effort to identify and manage projects that both feel good and do good. IMO it is a fine thing to purchase these offsets for emissions that we cannot easily avoid right now.

But (and there’s always a but). We need to keep top of mind that even the best carbon offsets (6) are a band-aid for countries’ unwillingness to make effective policy and for individuals’ unwillingness to reduce our own emissions. We have some choices to make. Do we want to save our natural resources at scale? Where and how should that happen? Recently (very expensive) mechanical offsets have become available through Climeworks, with precise carbon dioxide reductions but no co-benefits. Do we optimize for a world of mechanical carbon balance or of natural carbon balance? Which is faster? Cheaper? I prefer a natural balance, but I’m pretty sure that moneyed interests prefer a mechanical balance because there is more they can contribute (and earn) and more room for human innovation. What balance do we strike, and how? And how does that affect where you put your own money?

So, for now, yes, go ahead and offset your emissions. It can do good. But the voluntary offset model cannot match the scale and urgency of the challenges we face. Consider the other pillars of climate action -- individual action, political engagement, financial investment and divestment -- and think what more you can do, both at home and at work, to create the future you are looking for.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on carbon offsets, your experience with them, and how you believe they impact people (both beneficiaries and funders) and the planet.

Notes and References

1. Flaring (burning) methane converts the methane to carbon dioxide, which is an overall improvement in emissions since methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas, at least while it persists in the atmosphere.

2. Biocarbon Partners says that Zambia’s deforestation is the highest in Africa, with an average of more than 1,000 square miles of wildlife habitat disappearing each year. The areas they are protecting provide habitat for the African wild dog, Temminck’s pangolin, the leopard, lion and elephant, among others.

3. In part because costs change over the lifetime of a project, offset vendor Atmosfair doesn’t publish the prices of its projects or give consumers a choice of project, as explained in its interesting FAQ on the topic. They charge a (rather high) flat fee of $25 per tonne of carbon.

4. I used to think that Americans should purchase offsets for US-based projects rather than projects in developing countries. Let’s clean up our own emissions before we interfere elsewhere. Let’s make our own country more sustainable. But now I see both sides. A dollar may go farther (clean up more emissions) elsewhere. Emissions from developed countries are hurting developing countries, so money should arguably flow in that same direction. And green improvements in developing countries can have more impact if they establish a working model for clean growth.

5. Lawrence says that interest in offsets “took off” after Greta Thunberg announced she would sail to New York. Purchases of individual travel offsets on the Cool Effect site have grown 700% since May. Business contracts have also “really stepped up. It’s night and day (from a year or two ago),” he says.

6. As I’ve tried to point out, offsets can be very “squishy”. It can be hard to establish an accounting baseline (what would happen if there were no project). It can be hard to ensure longevity. It can be hard to prevent leakage or problematic side-effects. The best offsets provide a constellation of social benefits as well as measurable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, but even those have uncertainty. At the end of the day, reducing your individual emissions is the surest thing you can do, but you can also have some impact through quality offsets. Some people use offsets to cover flights (Atmosfair has a particularly informative interface for this), but others cover the entirety of their household emissions. Because of the uncertainty around offsets, you might consider doubling the amount you purchase and diversifying your purchases. But keep in mind that the better offset projects maintain a pool of credits to use in case of unexpected problems, so your purchase already has a buffer in it.

7. The Carbon Offset Research and Education (CORE) initiative produces an excellent, comprehensive overview of carbon offsets. It is particularly useful for companies looking to offset emissions. National Geographic has a much shorter overview more targeted to individuals, as does NRDC.

8. Two people at the University of Pennsylvania have written a more prescriptive but still very informative overview of carbon offsets. (They wrote this while figuring out how best to offset the SIGPLAN conference.)

9. The Gold Standard has an interesting post about what carbon credits are worth. Carbon pricing in general is a good topic for a whole blog post because each country prices it differently (if at all), and the “social cost” of carbon may be different from any carbon tax, or any carbon credits.

10. ProPublica published a well-read article about the failures of carbon offsets, as well as a rebuttal to criticisms about that article. Ecosystem Marketplace has an interesting interview about practical challenges preserving forests in Asia.

11. You can read about the projects that Palo Alto Utilities funds to offset its customers’ use of natural gas.

12. Thank you to Palo Alto resident Bea Crystal for her help reaching out to Biocarbon Partners.

Current Climate Data (December 2019)

From CarbonBrief’s summary of its “How the world warmed in 2019” report: “2019 was the warmest year on record for ocean heat content, showing a marked increase from 2018…. With modern-era sea levels also now at a record high and Arctic sea ice and global glacier ice both continuing their dramatic downward trends, the report highlights just how many alarm bells are currently ringing in the data.”

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines, or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.