That is, concerns about sprawl are trumping concerns about traffic congestion. No longer will you see intersections rated with traffic grades from A-F. From CEQA’s point of view, an F on traffic is the lesser of two evils. A denser region is a greener region.

How did this come about, and will it help to reduce our emissions?

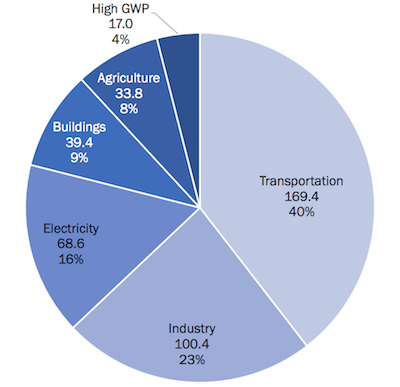

California is on a mission to reduce transportation emissions. This sector is by far the biggest source of emissions in California.

California's greenhouse gas emissions, 2016 (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

A full 70% of those emissions come from light-duty vehicles, which are cars and trucks weighing at most 8500 pounds. Other sectors -- freight, aviation, shipping, rail -- tend to be harder to decarbonize, so most of California’s specific policies to date are targeted at reductions for cars and light trucks. (1) (2)

California's transportation emissions 2016 (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

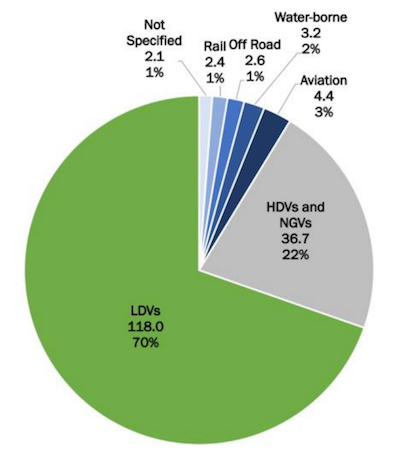

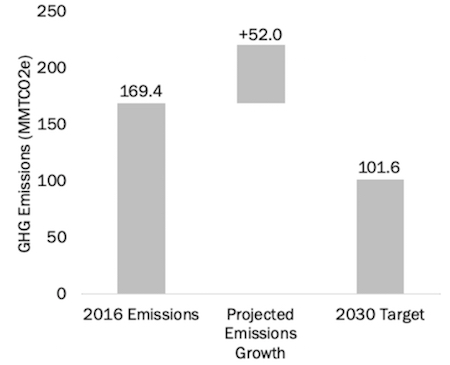

We cannot do this gently. Take a look at our emissions trajectories up until now, and where we need to go to hit our 2030 goals.

California's greenhouse gas emissions targets and progress through 2016 (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

You can see that the only area where we are making real progress is in reducing electricity emissions (yellow). The recession around 2008 helped some with transportation, but emissions have gone right back up. Moreover, the California Energy Commission expects that we will add about 30% more vehicles over and above the 2015 baseline by 2030, leading to this sobering chart showing the job ahead of us. We need to reduce transportation emissions by about 46% by 2030, and those of light-duty vehicles by more than that.

California’s projected transportation emissions (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

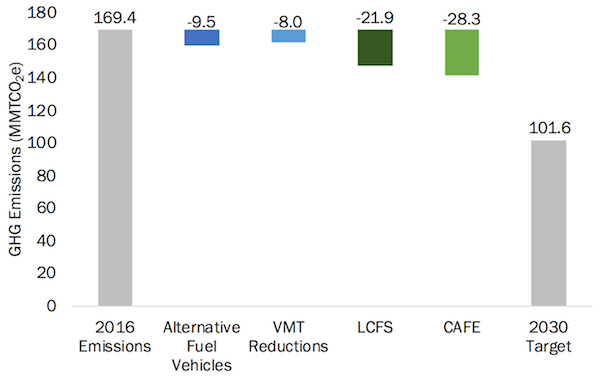

California has developed a four-pronged strategy to do this. These are listed in order of projected impact by 2030, from greatest to smallest.

- Improve fuel-efficiency of gas-powered cars. This is mainly the so-called CAFE standards that the federal government is trying to relax, but also includes things like encouraging people to drive smaller cars and even to drive more efficiently.

- Move to lower-carbon fuel. This is primarily blended fuels (e.g., with ethanol or renewable diesel), but also includes reducing emissions in the upstream supply chain.

- Move to alternative vehicles. This focuses largely on electric vehicles (and the infrastructure they require).

- Reduce demand. This includes promoting transit and telecommuting as well as increasing the density of jobs, housing, and services to reduce the need to travel.

The chart below shows the projected effects of this strategy. They are significant, though insufficient to account for the projected growth of vehicles, which is not shown on this chart. You can see that the strategies that involve changes to consumer behavior, primarily moving to electric vehicles and driving less, have lower projected impacts.

Projected impact of transportation emission reductions by 2030 (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

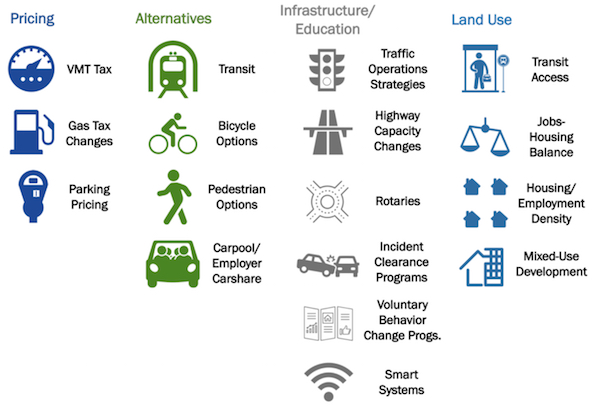

The CEQA change from measuring congestion to measuring VMT is directed at the fourth pillar in the list, namely reducing demand. The impetus for the change started over ten years ago. In 2008 Arnold Schwarzenegger signed SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act. To reduce vehicle miles, the act encourages development of denser communities, where many people don’t want or need cars, and more generally aims to penalize cars relative to other modes of transportation.

Transportation strategies for Sustainable Communities (Source: 2019 EFI Report)

But since it went into effect in 2009, per capita VMT hasn’t budged. On the land use side of things, planners noticed that the CEQA project analysis was essentially fighting against itself, with some sections (e.g., air quality) pushing for reduced VMT, but others (e.g., transportation) pushing for increased VMT to avoid congestion. The result was a tendency to encourage projects at the outer edges of a region, increasing travel distances but reducing congestion.

So in 2013 Governor Brown signed a bill (SB 743) to fix this problem and prioritize a reduction in VMT. As asserted in the Transportation Element of Palo Alto’s Comprehensive Plan “This shift recognizes that prioritizing the free flow of cars over any other roadway user contradicts State goals to reduce GHGs.” Five years and many discussions later, CEQA has been updated. Instead of requiring projects to look at how traffic at various intersections is affected, instead we will analyze changes in vehicle miles traveled. According to this helpful primer on the CEQA changes: “The shift to VMT analysis under CEQA is intended to encourage the development of jobs, housing, and commercial uses in closer proximity to each other and to transit.”

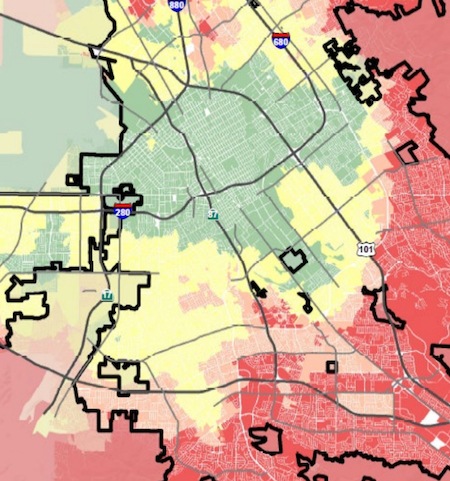

Local jurisdictions have some flexibility in how to measure VMT, which lower-VMT alternatives to consider, and how to mitigate any impacts on a regional basis. One interesting thing is that projects meeting certain criteria don’t need to do a VMT analysis at all -- they are automatically assumed to be good. For example, projects in low-VMT areas could bypass an analysis. See the green areas in San Jose, for example:

Lower VMT areas in San Jose (Source: OPR Technical Advisory)

Another exception is for projects near a train station or a stop on a “high quality transit corridor. (3) In our area, that would mean projects within a half mile of a Caltrain station or a bus stop on El Camino or University Avenue could ignore both traffic congestion and VMT in assessing CEQA’s transportation impact. (VMT is likely to come up elsewhere, though, for example in the context of air quality.)

There are lots more details. The full amendment is here, and the technical advisory is here. There is a short but useful primer here. But generally speaking, what do you think about this push to encourage density and discourage cars to help reduce our ever-growing transportation emissions?

My take: We need to take steps to reduce sprawl. We must be careful of how we use land, and low-density residential and commercial development spread over more and more land is not going to cut it. But we also need to acknowledge that putting more people in less space can be a difficult sell. As urban planner Brent Toderian puts it in a conversation with Vox’s David Roberts: “The city has to be able to virtually guarantee the quality of the outcome from the urban design, livability, multimodal perspective. And a lot of cities have not set up the culture, the structure, the capacity, the training, or the tools to deliver quality. So when NIMBYs express a fear of change over density, they’re often right…. Don’t let them be right, is what I’m saying.” He sets a high bar. I wonder, in reality, how much of what we will do will be redesigning cities versus redesigning the expectations of the next generations. I have yet to see a city that is clean, quiet, safe, green, and affordable. I have seen a few that mostly meet the first four. I’m not sure all five is even possible. That said, in our area, I expect there is plenty of room to grow without sacrificing quality of life. I just haven’t seen a real plan for what that looks like. I figure it needs to start with truly effective transit and dedicated areas of affordable housing, both of which can be expensive. Maybe that is the problem. Is there anything we can learn from Minneapolis’ 2040 plan? While we are putting more people in less space, I’d also like to see us protecting more open space from development, to better reinforce why we are densifying.

All of this imo is a long-term play. For the short-term, I would like to see us double-down on more straight-forward ways to reduce vehicle demand. Provide more support for alternative transportation modes like bikes, preserve local services, and see if there is a way to get transit working for more people. Traffic is going to get worse and more people will be looking for options. How can we help them? Encourage tele-commuting. When we can’t reduce demand, we should do more to ensure that miles that are traveled are electric and charged midday. Let’s build the used EV market and deploy charging infrastructure in all workplaces and parking areas. Create more incentives to move to EVs and, more generally, smaller cars. At the same time, keep pushing hard on the pathways of fuel efficiency and lower-carbon fuel.

Density is a tough sell in our community. But what if it were coupled with much-improved transit and alternative transportation for all, a more socio-economically diverse local community, and additional space protected from development? I’d be up for it. But what do you think about density? And how would you go about reducing miles traveled or more generally reducing transportation emissions?

Notes and References

0. Yes, that’s a Mick Mulvaney reference...

1. California’s Air Resources Board, which is the source for this data, indicates that these aviation emissions do not include interstate or international diesel.

2. LDV = Light Duty Vehicle. HDV = Heavy Duty Vehicle (e.g., large trucks, buses). NGV = Natural Gas Vehicle (there aren’t many of these).

3. There are some exceptions to this. For example, if a project has more than the minimum parking required, it needs to do a detailed VMT analysis, presumably because it seems to be encouraging car use. (Source: Office of Planning and Research’s Technical Advisory)

Current Climate Data (September 2019)

The global land and ocean surface temperature departure from average for September 2019 tied with 2015 as the highest for the month of September in the 140-year NOAA global temperature dataset record, which dates back to 1880.

Global impacts, US impacts, CO2 metric, Climate dashboard (updated annually)

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines, or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based and refer to reputable sources.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.