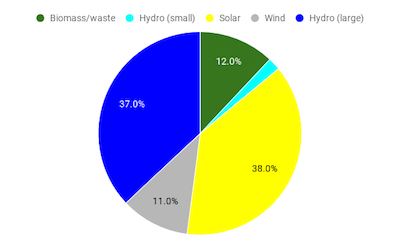

Palo Alto’s 2017 electric mix. Nailed it!

Not exactly. With markets changing rapidly and the concept of what is “clean” continuing to evolve, there are many difficult problems the city is working on. With a focus on affordability and sustainability, Palo Alto’s Jim Stack, Senior Resource Planner for Palo Alto Utilities, spends a lot of time on contracts and emissions accounting. Let’s take a closer look at what that involves.

Contracts

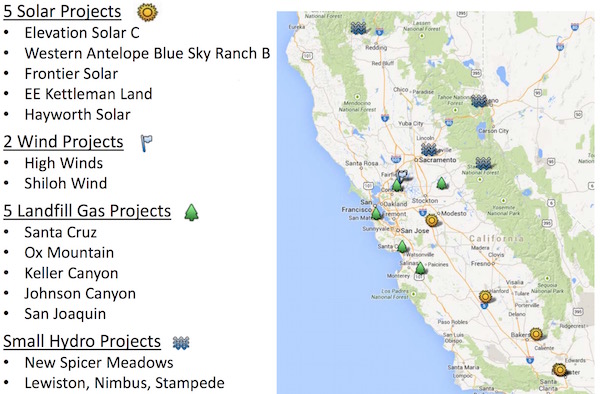

Palo Alto has 12 operating renewables contracts, 2 hydro contracts (covering several facilities, only the smaller of which are shown), and 6 small local solar contracts (not shown).

From a December 2016 presentation (1) to the California Energy Commission

With several of these coming up for renewal in the next few years, a number of questions arise, including:

- Should we renew our large hydropower contract, given so many uncertainties about hydropower’s long-term output and costs?

- Should we invest more in out-of-state wind, which (unlike local wind) produces more energy in fall and winter to balance our solar, but is more expensive due to transmission costs?

- Should we couple storage with some of our solar purchases, and at what price?

- Should we replace some of our intermittent wind with a more reliable (“baseload”) resource like landfill gas or geothermal energy?

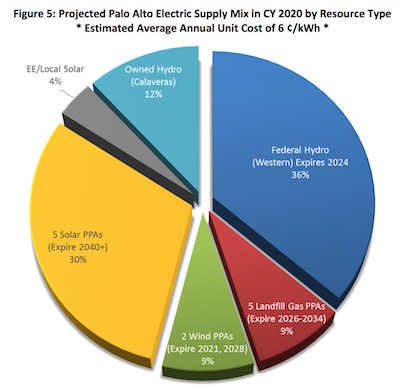

I don’t have space to cover all of this, though you can take a look at Palo Alto’s 2018 IRP or the Utilities Advisory Commission meetings to learn more. But let’s examine the toughest contract issue a bit more closely, namely the hydropower decision. Palo Alto’s biggest power source, nearly 40% in a normal water year, is a large federal hydropower facility in the Central Valley called Western Base Resource. We have a 20-year, fixed-share contract with them that is expiring in 2024. (In the picture below, PPA = Power Purchase Agreement)

From Palo Alto’s 2018 Integrated Resource Plan

We need to decide whether to renew it for another 30 years (the term the government is offering). The difficult part is that there are many unknowns. To give you a flavor:

- Hydropower can be highly variable year to year due to precipitation changes. Plus the longer-term effect of climate change on California’s hydropower is not clear.

- Many other uses compete for this hydropower, including flood control, irrigation, and recreational use. Power generation is the lowest priority, which aggravates the supply uncertainty.

- Environmental regulations that may affect supply are evolving. For example, a proposed “unimpaired flow” to the Delta directive could impinge on power supply in summer.

- State mandates around renewables may get more stringent, and large hydropower is not considered renewable.

- Western is still in the process of doing a study to estimate its costs and allocate them to the various types of customers using the system (e.g., power users vs irrigation users), while legal uncertainty exists around (significant) fees assessed to customers for environmental restoration.

The city is looking to better understand these uncertainties and add contract protections like a termination provision, while also assessing the overall portfolio to determine how much hydropower we want to lock in.

Emissions Accounting

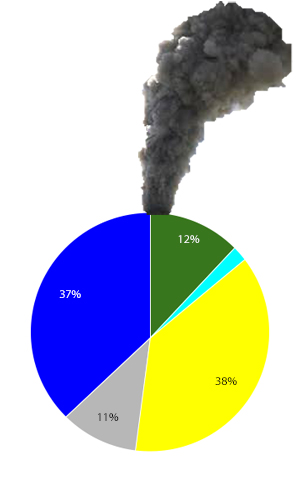

Another topic Jim spends a lot of time on is sustainability, and specifically reducing our carbon emissions. Because right now our electric power is dependent on fossil fuels. Here is why.

Wait, is this what Palo Alto’s electricity looks like?

The emissions information that utilities in the state have been asked to report is based on “net annual usage”. What does that mean? Utilities consume power from the grid, based on their load minus whatever local resources they have (typically rooftop solar). Utilities also put power onto the grid, based on generation stemming from their purchase contracts. Their net usage is what they consume (take from the grid) minus what they generate (put onto the grid). Calculated over a year it becomes the “net annual usage”. If a utility contributes as much clean power to the grid as they consume, over the course of the year, then they can claim “carbon neutral power based on net annual usage”.

This used to be a fair approximation for “carbon-free” power, back when the primary carbon-free sources were relatively steady “baseload” resources like geothermal and hydro. But with intermittent resources like solar and wind gaining share, Palo Alto and other clean utilities are looking to tighten up the reporting.

Consider a utility that contracts for 100% solar power. It puts lots of solar power on the grid during the day, especially in spring and summer. But it purchases from the grid 24x7 and year-round. While this utility is “carbon neutral based on net annual usage”, it clearly relies on the grid’s dirty power for its operation. In fact, it would not be possible for all utilities to be “clean” in this way, because this utility is trading cheap midday power that is not very useful (2) for more valuable power in evenings and winters.

So Palo Alto and other utilities (like Peninsula Clean Energy) are looking to adopt more stringent standards for being carbon neutral.

You can imagine, for example, looking at purchases and consumption on an hourly basis instead of on an annual basis. If utilities aim to match generation with load on an hourly basis, they will need to generate as much power as they use in evenings and in winters, and more generally for every hour of every day. There would still be some averaging (within the hour interval), but it is a far cry from averaging over the year.

Another approach would be to verify that the value of the clean power a utility is putting onto the grid is at least the value they are consuming from the grid, where value reflects demand relative to clean supply. For example, power drawn from the grid at midday would have less value than power drawn in the evening, because clean power is more available midday. Similarly, summer power would be less valuable than winter. This accounting would prevent a utility from equally exchanging midday solar for evening power. Palo Alto has looked at a variant of this, involving marginal emissions rates computed on an hourly basis. (3)

Is Palo Alto still “carbon neutral” when using these stricter grading protocols? Palo Alto manages its portfolio primarily on price, for example selling its excess hydropower during evenings when it is most valuable. Because grid pricing is somewhat aligned with marginal emissions, Palo Alto fares well when using that standard. In fact, Palo Alto pencils out slightly better than carbon-neutral (i.e., negative emissions) when using the marginal emissions rate accounting method. But the city’s power is dirtier using the hourly average standard, and in 2018 would not have been considered carbon-neutral. The city is continuing to work with other utilities and the state on which method makes the most sense.

The point is: details matter. In the case of hydropower, we need to do our best to assess unknowns, then figure out how to hedge our power portfolio accordingly. At a state level, if we model power emissions incorrectly, California could declare “carbon neutral” power despite a reliance on fossil fuels. And you can imagine the impact of how we define things like carbon taxes and emission metrics at the federal and global levels. We need smart, thoughtful people who care about our climate first and foremost developing and iterating on these policies, and voters who pay attention.

Notes and References

1. Here is the presentation to the California Energy Commission.

2. California often has such an excess of midday solar power that it will pay other states to take it. If you've heard that before, it can be fun to actually see it.

3. From Jim’s recent staff report on emissions accounting options: “Marginal emissions factors are a measurement of how the grid’s emissions change with a small change in electricity load. In other words, if one were to add one MWh of load to the grid during a given hour, the marginal emissions factor would be the emissions factor of the power plant whose output would increase to serve that one MWh. Marginal emissions rates take into account the operating cost of different types of power plants, telling you that when total demand is low the units with the lowest operating costs (which are typically the most efficient and least polluting units) are the ones that stay online; and as demand ramps up, the grid operator calls on increasingly costly (and higher polluting) units to meet the incremental demand.”

Current Climate Data

The Guardian recently decided to include global CO2 levels in its weather forecast. In that same vein, I will now be including these links to current climate data with each post.

Climate dashboard, Global impacts last month, US impacts last month, CO2 metric last month

Comment Guidelines

I hope that your contributions will be an important part of this blog. To keep the discussion productive, please adhere to these guidelines, or your comment may be moderated:

- Avoid disrespectful, disparaging, snide, angry, or ad hominem comments.

- Stay fact-based, and provide references (esp links) as helpful.

- Stay on topic.

- In general, maintain this as a welcoming space for all readers.