Queen Anne-style homes, recognizable for their corner towers and flamboyant gables, began popping up in Palo Alto’s earliest neighborhoods near the turn of the 20th century.

With decorative trim, towers and turrets, the Queen Anne architectural style has been called a collision of volumes and elaborate features. Originally an English style formulated in the 1860s, the Queen Anne went through many transformations before it arrived in Palo Alto in the 1890s.

The emergence of these Victorian homes in Palo Alto can be linked with the opening of Stanford University in 1891, which brought many young professors from the east and Midwest who chose to buy their own lots rather than lease campus land. As a result, some of the best examples of Queen Anne homes in Palo Alto were built between 1893 and 1898 in the College Terrace and Professorville neighborhoods, which were not part of the Stanford campus.

Leland Stanford reportedly was never able to negotiate the purchase of the farmland that became College Terrace and later part of the town of Mayfield. And so many professors bought property just beyond the campus in the area south of Homer Avenue in Palo Alto that the neighborhood became known as Professorville.

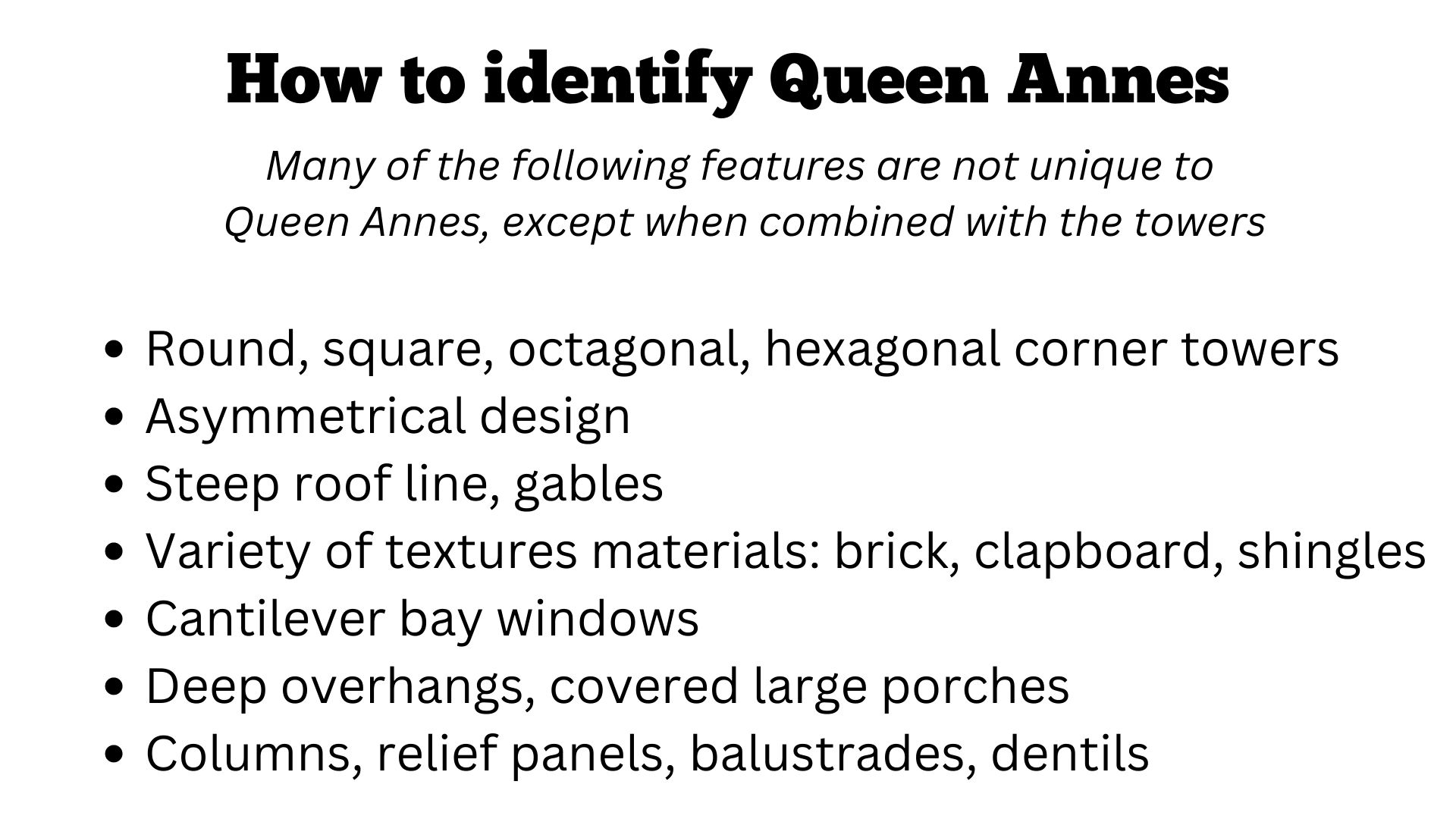

Anyone who has driven through Palo Alto has probably seen at least one Queen Anne. These homes resemble earlier Victorians but are much less formal and include details reflective of the era’s opulent lifestyle, such as steeply pitched roofs, relief panels that fill triangular pediments, patterned shingles, fake half-timbering, brightly colored siding with contrasting trim, balconies, large wraparound porches with classical columns, bay windows and ornamental trim details. The most readily identifiable feature of a Queen Anne, however, is its broad, round tower with a conical roof, usually found on just one of a home’s corners, making the façade asymmetrical.

But since Queen Anne is not a straight style, many variations of its key features can be found in Palo Alto. Two houses built on Stanford University’s campus in 1892, for example, have matching round towers on both front corners. These mirror-image Queen Anne homes were designed by Charles Edward Hodges, the university’s resident architect appointed by Leland and Jane Stanford. The houses originally backed up to each other on faculty rows. They now sit side by side on O’Connor Lane.

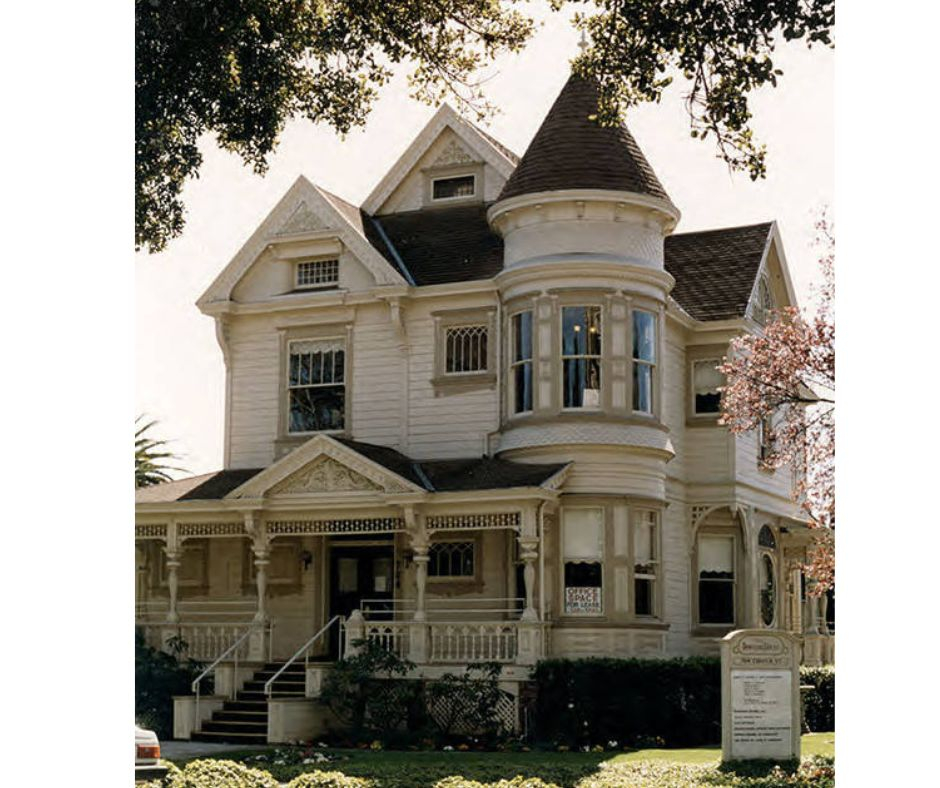

In downtown Palo Alto is an ornate 1893 Queen Anne with a single corner tower. Tucked between a single-story commercial mall and a four-story parking lot at 418 Florence St., the home was relocated from its original location on the corner of Bryant Street and University Avenue to clear space in the busy commercial district in the years immediately following the city’s incorporation in 1894.

And Palo Alto’s Queen Anne towers aren’t always round, either. The home at 2275 Amherst St. has a square tower and pyramid roof. Another at 510 Waverley St. has a hexagonal tower facing the rear door of Starbucks.

In addition to the large Queen Annes, single-story cottages also were built with minor stylistic flourishes, such as those located at 1215 Stanford Ave. and https://www.pastheritage.org/inv/InvS/Stanford1229.html 1229 Stanford Ave. These smaller cottages are called “restrained Queen Annes.” One common feature most all Queen Annes shared at one time was their bright exteriors. A Queen Anne’s colors could brighten even the stiffest Victorian. The 1890s Queen Annes of Palo Alto have been variously colored over the years, but most now are subdued.

The city’s most notable and best example of a “fanciful full-blown Queen Anne” is located at 1023 Forest Ave., which at one time was located just outside the city limits. The house has mismatched round towers at both front corners. The larger right-hand tower had a conical roof, made of copper, which was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, perhaps by a collapse of the adjacent brick chimney. Stored for years in the basement, the cap was eventually scrapped for metal in World War I, and the tower now has a flat roof. The façade is far from symmetrical but does have both unique and repeating trim patterns, enhanced by the detailed blue and white paint scheme. The home has been called “the Grande Dame of Crescent Park.”

Bo Crane is a Palo Alto native and graduate of Stanford University. As secretary of Palo Alto Stanford Heritage, he organizes and leads architectural/historical tours of Palo Alto neighborhoods. He also is a board member of Palo Alto Historical Association and historian for the Menlo Park Historical Association. This piece was originally published in the Palo Alto Weekly’s spring Home & Garden magazine.

Comments