When Laura Toller Gardner stepped into her job as the new CEO of the Redwood City-based nonprofit in March, Pets In Need, there was no time for a honeymoon.

The contract between Pets In Need and the city of Palo Alto was about to expire, and despite the agency having announced in 2021 it would not renew their partnership due to the city's alleged breach of their agreement, the nonprofit this spring was signing stop-gap extensions with the city while negotiating a long-term renewal.

Pets In Need's finances had taken a sizable hit, for reasons that the organization attributes to the growing costs of labor and medical supplies and the roughly $500,000 that it has been spending annually to subsidize its Palo Alto operations, Toller Gardner said.

Relations between the organization's Redwood City and Palo Alto branches were also at a low point, and several Pets In Need employees, including its medical director, programs director and human resources director, were on the way out, having been either forced out or fired for reasons that some of their colleagues felt were unjust.

Also, people were talking. Within her first few weeks on the job, Toller Gardner found herself responding to a social media post that accused Pets In Need — a "no kill" shelter — of becoming a "high-kill" shelter with a rising euthanasia rate.

It's a claim that Pets In Need leaders strongly denied.

Similar calls were coming from inside the house. Several past and current Pets In Need staff members have told this publication that they saw an increase in euthanasia, and City Council members were hearing rumors about this trend in public communications.

"It’s sad because we’re supposed to be an organization that saves animals, but we’re doing the opposite — we’re killing animals,” said one current employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity to protect their employment.

The nonprofit's official numbers also show a recent increase in euthanasia, with 12 cases in 2020, 18 in 2021 and 25 in 2022. The agency also reported five instances of euthanasia in the first three-and-a-half months of this year. The period, however, corresponds to a growing number of intakes at the shelters, which makes it difficult to determine whether the increase is a result of policy changes, as critics maintain, or merely reflects the growing animal population.

The case that triggered the April social media post involved Deanne Rosten, who for the past seven years has had an agreement with Pets In Need to foster a terrier mix named Jasper and a chow mix named Brodie.

Under the agreement, Pets In Need provided $500 per month to Rosten for each dog for food, medicine and other expenses. That is, until April, when Rosten received a letter from Pets In Need informing her that she would have to surrender Brodie and Jasper.

Rosten, who runs a kennel in Weldon, a small town next to Lake Isabella, said both dogs can be intimidating to strangers. They lunge and growl when someone drives by, she said, but are generally friendly, deeply loyal and very protective of her. Rosten said she feared what would happen if they were taken away from her.

"I lost it,” Rosten told this publication. "Over my dead body are they going to take these dogs! Why? Just to euthanize them? Forget that! They’re doing great at my kennel.”

Rosten wasn’t the only person unnerved by recent changes at Pets In Need, which greatly expanded in 2019 when it took over operations of Palo Alto’s animal services.

For months, longtime volunteers and staff members have been raising concerns about changes in the nonprofit's staff and policies and alleging that more animals are now being returned, medicated and, in some cases, put to death unnecessarily.

Since 2021, Pets In Need has gone through four different leaders and has seen dozens of staff members depart. Its good name took a hit in August 2021, when seven puppies in its care died in a van during a rescue run from the Central Valley — an incident widely referred to as Puppygate.

Azeel Buksh, who worked as program manager at Pets In Need, said that over the past two years, as the organization went through various leadership and policy changes, its historic commitment to being a no-kill shelter has waned.

"We made it work all through COVID, then things just started going downhill," he said.

But the nonprofit's executives strongly dispute accusations that more animals are being euthanized, pointing to the agency's high "live release" rate — a key metric that measures the percentage of animals that get either reunited, released or rescued.

Pets In Need's official statistics continued to show a "live release" rate of 98% — well above the 90% mark that designates "no-kill" shelters. Critics counter that these numbers don't take into account all animals that perish.

They exclude, for instance, those that die in shelter care, whether at one of its two facilities or while in foster care. There were 15 such cases in 2021 alone, according to Pets In Need statistics.

Critics recall by name the shelter animals who did not make it out to forever homes.

Defenders of the organization point to numbers: 690 adoptions in 2021 and 580 in 2022.

Both sides are making their respective cases just as Palo Alto is preparing to ink a long-term extension of its contract with Pets In Need to run the local animal shelter, a deal that could be finalized on Aug. 14.

ALLEGATIONS AND ACCUSATIONS

Recent interviews with current and past Pets In Need staff, leaders, clients and volunteers as well as documents obtained by this publication through the California Public Records Act, paint a picture of an agency that has never recovered from the 2021 Puppygate incident.

It remains hobbled by distrust, squabbling factions and leadership turnover that has forced some employees and volunteers to question the agency’s mission and its operations.

The allegations and accusations became louder this past spring, just as Pets In Need was ramping up its negotiations with Palo Alto for a new long-term contract to provide animal services.

The deal that the council will consider Monday would hike the city’s annual payments to the nonprofit from $773,580 to $1.37 million while eliminating some of the services that the shelter has traditionally provided, including after-hours veterinary care and veterinary services for cruelty investigations.

While the council signaled in June that it plans to go ahead with a new contract, some in the local animal-rescue community think that’s a terrible idea and are urging city leaders to consider other options. They're calling for the city to revert to the in-house model that was in place before Pets In Need came in or even outsource the animal shelter operations altogether.

Jeremy Robinson, one of the founders of the nonprofit Friends of Palo Alto Animal Services, is among those who believe that Pets In Need is no longer fulfilling its historic mission.

Before Palo Alto signed the initial contract with Pets In Need, Robinson and her friend Scottie Zimmerman, a longtime Pets In Need donor and volunteer, visited about 10 shelters in the region to get a sense of best practices.

Robinson also took trips to Winnipeg, Canada, and to Gainesville, Florida, to look at recently constructed shelters and even went as far as discussing with an architect potential features that could enhance the Palo Alto facility. (A 2015 review by the city auditor described the shelter as "outdated and inadequate to meet modern animal-care standards.”)

"That’s how confident we were that this was going to be a wonderful shelter, that this was going to be the beginning of a whole new era in Palo Alto with animals,” Robinson said in an interview.

"And then this decay began in Palo Alto and went underground and went to Redwood City and corrupted everything in between. That’s the way it seems — a downhill course right from the beginning.”

Like others in the community, Robinson said she is concerned about the growing number of animal deaths at the shelter.

Recently departed employees have described an environment in which Pets In Need leaders are more concerned about moving animals out of the shelter — by whatever means necessary — than saving them.

But Laura Birdsall, who joined the organization a year ago as director of shelter of operations, said while giving a tour of the shelter's two cat rooms that Pets In Needs does indeed try to move animals out of the shelter as quickly as possible.

She said this is for the animals' own good. Cats and kittens, for example, do much better in homes than they do in cages. And prospective adopters can learn much more about the animals after they've lived in other homes, she said.

"A home is where they want to be," she said during the tour. "So it really helps us manage the population in a way that's meaningful.

"One of the things we get as requests from adopters all the time is, 'What's this cat like?' Well, I can tell you what this cat is like in a shelter. But he may go home and be completely different."

The nonprofit’s annual report suggests that the euthanasia levels remain below what they were when city staff ran the shelter. The report shows that in 2017 and 2018, just prior to the takeover by Pets In Need, the Palo Alto shelter euthanized 38 animals per year. Even that was a drop from 2014, when there were 97 euthanasias and 2015, when there were 72.

GROWING FACTIONS, DISTRUST

Even as euthanasia numbers remain disputed, it’s hard to contest the notion that the organization has gotten increasingly toxic and factionalized over the past two years.

Several current Pets In Need employees, both past and present, describe an organization that has been hobbled by internal conflicts and distrust between its Palo Alto and Redwood City operations.

Some of these tensions reflect the historical differences between Pets In Need and Palo Alto Animal Services. The former is a rescue nonprofit with a mission to save as many dogs and cats as it can; the latter a municipal operation charged with handling the myriad animal-related services and problems in the communities that it serves.

The former boasts a wider network of foster families and volunteers; the latter a keener understanding of local conditions.

Jeanette Washington, who has been an animal control officer in Palo Alto for more than 20 years, suggested during a June public hearing that Pets In Need does not have the expertise to handle a municipal operation.

"A municipal shelter does more than just adoption,” Washington told the council. "Unlike a rescue, it doesn’t get to pick and choose what animals it helps. We must be ready and willing to work with animals with challenging behaviors and give every single one a fair chance.

"It acts as a safety net for all animals in the community and provides essential services for its citizens and pets.”

Given the inherent differences between Pets In Need's operation, which allows it to choose which animals it accepts at its Redwood City facility, and Palo Alto's municipal shelter, which has to take all animals that are brought in, comparing the "live release" rates can be challenging.

Al Mollica, who served as Pets In Need's executive director when the organization began its current contract with Palo Alto and who resigned shortly after the puppy incident, said some municipal shelters simply don't have the staffing and resources to deal with a surge in demand for shelter space.

It's simply impossible for them to achieve a "no kill" status.

Mollica, who declined to discuss Pets In Need for legal reasons, last year launched a nonprofit called Partners for Animal Welfare (PAW) to help these shelters.

The group provides free spay and neuter services in municipalities like San Jose, where the shelter is overwhelmed with animals because of inadequate resources, he said in an interview.

As of mid-July, Mollica's nonprofit held five clinics, including several in San Jose and one in North Fair Oaks in unincorporated San Mateo County. He hopes to raise more money through grants and host more clinics to manage the long-term problem of animal overpopulation in these communities.

Mollica said the idea of a "no-kill" shelter, as defined by a 90% live-release rate, has influenced how some shelters behave, putting pressure on them to "fudge the numbers so they can magically become no-kill shelters."

This could mean adopting tactics like having animal control officers euthanize animals in the field or not accepting animals that are ill.

"I can say in good conscience that I never did that, but I'm aware of shelters, particularly back East, that were doing that pretty regularly," he said.

Pets In Need sees its extensive foster network as a key tool in keeping the Palo Alto shelter well above the 90% threshold.

Toller Gardner said she believes having a "hybrid shelter" — with limited intake in Redwood City and open intake in Palo Alto — is poised to make a "huge impact in the community."

But the historic differences have also complicated the Palo Alto partnership. Kelsey Uhlin, who worked as an adoption specialist at Pets In Need in Palo Alto, said the inherent difference between the two branches created some tensions between the Redwood City and Palo Alto staff.

"Palo Alto is a municipal shelter and Redwood City is a rescue and primarily an adoption center, so they (Palo Alto staff) believed it should be two different operations instead of one joint operation — that Redwood City didn’t understand everything Palo Alto was going through and vice versa,” Uhlin said.

"There were a few of us who believed we should be able to work together because we are one organization.

"But Palo Alto thought there was a lot of smack talking coming from Redwood City, and Redwood City thought there was a lot of smack talking coming from Palo Alto.”

The simmering tensions came to a boil in August 2021, after the seven puppies died while in a Pets In Need van. The puppies were picked up in the middle of a rescue run and, according to Pets In Need staff, were reportedly already sick when taken into the nonprofit's custody.

Once the dogs arrived at the Palo Alto shelter, an animal control officer referred the incident to the Police Department, which initiated an investigation of the three Pets In Need staff members who took part in the rescue run.

The incident deepened a fissure within the organization. Everyone agreed that what happened was a tragedy; some in Palo Alto also treated it as a crime. A group of shelter employees issued a public letter that accused the three Redwood City-based workers involved in the transport of negligence.

The letter described what happened as "blatant disregard for sentient life and the antithesis of what Pets In Need or animal rescue and advocacy is about.”

Things got testier in October 2021, when the Santa Clara County District Attorney filed two misdemeanor charges against the three employees. Furious about how the city had handled the incident, Pets In Need notified the city in November 2021 that the organization would be terminating its agreement with Palo Alto within a year. The following month, Mollica abruptly resigned.

The incident sent shockwaves through the organization and the wider animal-rescue community. Valerie McCarthy, a former Pets In Need board member who succeeded Mollica as executive director, attempted to do damage control.

She assured the Palo Alto council at a February 2022 public hearing that the organization used the tragic puppy incident as "an opportunity to continually improve our day-to-day operations.”

"I feel like we're actually much better than we were before," McCarthy told the council.

But some longtime staff members contend that the opposite was true.

"Once Puppygate happened, everything kind of fell apart after that,” said Buksh, who worked out of the Redwood City facility.

"Everyone in Palo Alto just went, ‘We need to get these guys out of here.’ Everyone in Redwood City felt like this was a huge accident but there’s no fingers to point here. This is where my mindset now became: There is Redwood City; and there is Palo Alto.”

STAFFING TURNOVER AND TURMOIL

Former staff have also accused Pets In Need's top executives of fostering a dysfunctional and hostile environment and forcing out various longtime staff members. These included, among others, program director Marsa Hollander, veterinarian Dr. Angelo Stanton, and Sandra Chew, the nonprofit’s human resources director.

Buksh, who resigned from Pets In Need in May, said the departure of Hollander, his former boss, hit him particularly hard.

The nonprofit’s most recent annual report lauded Hollander for her "energetic, entrepreneurial” demeanor and a "warm extroversion” that "nurtures outside-the-box thinking.”

In her nine years at Pets In Need, Hollander had spearheaded various community outreach programs.

The Pets In Need report highlights the partnership that Hollander forged with the nonprofit LifeMoves to provide summer camps for children at LifeMoves shelters — a program that reached 200 students from 10 LifeMoves facilities in the summer of 2022.

Hollander is also friends with Rosten and had helped engineer Rosten’s arrangement with Pets In Need for Jasper and Brodie.

While Hollander declined to discuss the circumstances of her departure under the advice of her attorney, others have said that she was effectively fired for opposing the Pets In Need leadership’s decision to cut off payments to Rosten.

Buksh and other staff based in Redwood City said Hollander was suspended and then fired after a tense conversation with former Executive Director Teri Dunwoody over the arrangement. They felt the firing was unfair.

Buksh had also become increasingly concerned about how the animals at the two shelters were being treated under the new Pets In Need leadership, which includes Dr. Barbara Laderman-Jones, the new medical director, and Birdsall, director of shelter operations.

More and more dogs were being sedated through medication. At times, a dog would be adopted and then returned to the shelter, where it would be forced to readjust, they said.

"Now, every dog on the adoption floor, whether in Palo Alto or Redwood City, is medicated,” Buksh said. "The animals get adopted and come back and they’re no longer acclimated and are getting kennel crazy.”

The stress of going back and forth takes its toll on the animals and some act up once they return to the shelter, at times with fatal consequences, several staff members told this publication.

Buksh recalled doing his rounds through the adoption area in the morning, checking in on the animals to see which would do well in group settings. There were times, he said, when he would ask about a dog and was told that it has "behavioral issues.”

"That means they euthanized the dog,” Buksh said.

Other former and current staff member also said that they had observed an uptick in the administration of medication and of euthanasia in recent months at both the Redwood City and Palo Alto facilities.

Some said they believed just about every dog at the shelters was under medication, which often created a false impression for would-be adopters and which led to more pets being returned.

When asked about this, Toller Gardner said that providing medication for dogs and cats in shelter care demonstrates the organization's increased effort in "caring for the physical and mental/emotional wellbeing of our animals."

Since the fall of 2022, the nonprofit has been working with a veterinary behaviorist whose support includes medication for animals that experience kennel stress, panic and anxiety, she said.

The nonprofit, Toller Gardner said, brings all resources to bear to help the animals stay calm and confident while in the shelter.

"Additionally, research has shown us that you cannot get an accurate impression of an animal in the shelter setting — it is too crowded/noisy/unfamiliar/stressful," she said in an email.

"Providing the dogs (and cats) with medications to help them cope with the stress of being in the shelter is not only humane, it also allows the adopters to see what the animals (are) like when less stressed."

"We are investing in best sheltering practices to serve our animals in the best way possible, and medication for the animals that need it are part of those practices," she said.

Some staff, like Buksh, felt the new medication policy went too far. He said he has always taken pride in working with Pets In Need and lauded Hollander for showing him a "new perspective on life where I can do better and help people.” For years, he felt like he was doing something good, he said.

But after Hollander was fired, he knew he couldn’t stay.

He left, unable to deal with what he perceived to be the new leadership's treatment of both people and animals.

"That was the one reason I was there for so long, because of the no-kill thing,” Buksh said. "When you said 'PIN,' the immediate thing that came to mind was 'no-kill.’

"That made me feel good in the place I work in, that we were willing to go above and beyond. But it’s so loose now.”

TRYING TO RESOLVE DIFFERENCES

Sandra Chew’s career as Pets In Need human resources director also came to a jarring halt this past spring.

Chew said that when she started working for the organization in March 2022, she witnessed firsthand the animosity between Palo Alto and Redwood City staff.

Chew described the atmosphere at Pets In Need as toxic, with Redwood City and Palo Alto employees squabbling and the new senior leadership generally siding with the Palo Alto faction.

The nonprofit’s attempts to contain the damage by hiring a coach and holding regular workshops failed to bridge the gap, she said.

They did, however, cost the organization tens of thousands of dollars and forced it to close down the shelter for afternoon workshops, she said.

"It was always during the day that the shelter was open, so we had to shut it down,” Chew said. "So it meant another day lost for showing animals.”

Both she and Buksh said the workshops did not achieve anything, an assessment that others also shared with this publication.

"They’ve been spending a lot of money on unnecessary training and on staffing that a lot of employees feel is unnecessary,” said one current employee who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Chew said the stresses of the job took their toll, particularly after she declined to discipline a Redwood City employee who in her off-hours allegedly made a disparaging comment about a Palo Alto employee.

Dunwoody had allegedly pressed Chew to fire the employee, and Chew said she had resisted this direction.

The disputes affected her job as she found herself responding to employee conflicts and debating disciplining decisions with Pets In Need leaders.

After one such disagreement with Dunwoody, Chew went on leave. She then resigned days later.

"I thought when things could not go any further down, they did,” Chew said. "I’m actually amazed at things that are happening. It’s like watching a horrible accident happening as we speak.”

Toller Gardner said that Pets In Need would not respond to any questions pertaining to the organization's HR disputes, citing state laws that protect employee privacy. Nor would she make Dunwoody available for an interview to discuss allegations made by Chew and others.

"There were some changes that needed to be made when I first arrived," Toller Gardner said of the recent staff departures, "and we made those changes."

For those who oppose extending the Pets In Need contract with Palo Alto, the recent staff turnover is prime evidence of an organization in disarray.

Kadri Corollo, a Palo Alto animal control officer, said that more than 50 staff members have left or had been fired since 2019 — a turnover rate of more than 100%. This turnover has created issues of staff being "untrained, unknowledgeable of policies and procedures and low job performance,” Corollo told the council on June 12.

"This instability makes it difficult for the shelter to run efficiently,” Corollo said.

The turnover also has not gone unnoticed in the wider community.

Pam Zink, who has fostered cats for Pets In Need in the past, tried to do so last fall but did not get a response from the agency, she told this publication.

She had come to know over the years some of the recently departed staff members, including Hollander, and said she was concerned about the impacts of the recent leadership change on the Redwood City facility.

"Who is driving this boat?” Zink asked. "Who is causing all these shifts and the turnover and making all these decisions and why did it all change?”

In late June, as talks between Palo Alto management and Pets In Need continued to advance, Jeremy Robinson sent a letter to the council urging it to reconsider the contract.

"I must ask why no one is curious about why most of the prior managers have left PIN, why so many staff members have left, why they have trouble keeping even new staff, why there is such intense hostility between the two locations,” Robinson wrote.

"And I wonder why it took 18 months to find a new executive director, settling finally on someone who is totally ill equipped to manage the organization, as is obvious from the current sorry state of affairs.”

Not everyone shares the view. Scottie Zimmerman, Robinson’s friend and fellow co-founder of Friends of Palo Alto Animal Services, defends Pets In Need from the recent criticism.

Zimmerman said she’s been hearing "unfortunate rumors” about euthanasia but believes, based on her conversations with shelter staff, that the shelter’s operations are going well.

"A lot of people who have resented PIN for taking the shelter away from the PAPD (Palo Alto Police Department) are speaking up and making claims that can’t be verified as far as I know,” Zimmerman said.

Zimmerman urged the council and City Manager Ed Shikada to retain Pets In Need, citing its record during the pandemic of enlisting more than 150 fosters to take care of animals while the shelter shut down because of COVID-19 in spring 2020.

She also said she does not believe the allegation of unjustified euthanasia and personal attacks on Pets In Need staff, which she argued was an outgrowth of the August 2021 episode involving the seven puppies.

"I think it would be a sad mistake to let the PIN contract lapse and turn the shelter operation over again to PAPD,” Zimmerman wrote to the council in June.

Toller Gardner's supporters also push back at the notion that she is "ill equipped" to manage the organization. A nonprofit executive with experience in fundraising and marketing, she boasts a resume that includes as its most recent entry a stint as chief marketing and business systems officer at the Oshman Jewish Family JCC in Palo Alto.

In announcing Toller Gardner's appointment in March, Robert Kalman, chair of the Pets In Need board of directors, praised her as a "visionary leader whose transformative approach and embrace of innovation and creativity are exactly what PIN needs at this exciting time in its evolution."

Birdsall said in an interview that longtime shelter employees don't necessarily make the best leaders, a position that requires an ability to craft a vision, run a large organization and inspire employees.

"I cannot lean into what Laura brings to the table enough. I can teach anybody to run a shelter. But to run an organization in a meaningful way and to bring all of the different collaborators together? That's a skill set," Birdsall said.

In discussing her background, Toller Gardner highlighted her 40 years of involvement in animal rescues.

The announcement of her appointment cites her stints as a volunteer adoption counselor for Nike Animal Rescue Foundation and a foster and adoptions volunteer with Unconditional Love Animal Rescue.

"I have seen the difference that animals make for human beings, for families and what families do for animals," she said when asked why she wanted to take the job.

"And what I know from personal experience and from all the data is that in the United States, there is a companion animal overpopulation epidemic we cannot rescue and shelter our way out of. So it's going to be very, very critical."

Toller Gardner said that when she began her job in March she had three main goals: understand the organization's operations and staffing, develop a good relationship with the city and work well with the organization's board of directors and donor supporters.

Given the staffing issues, she will also have to create a vision that all employees can embrace and find a way to restore trust and raise morale.

THE DECISION TO EUTHANIZE

In a March presentation to the City Council, Pets In Need’s newly hired director of shelter medicine, Dr. Barbara Laderman-Jones, responded to a question from City Council member Julie Lythcott-Haims about the organization’s euthanasia parameters by saying the organization has "an obligation to our communities to place only safe animals in the community.”

"There are some dogs that do not meet the criteria of being safe and do need to be euthanized. So we’re realistic and as responsible as we can be.”

Days later, however, the council received a letter alleging that the organization’s policies on euthanasia have become too permissive of the practice.

The author was Tera McCurry, executive director of Doggie Protective Services, an adoption organization that has been operating in northern California since 2008. Several of its volunteers were at one time employees or volunteered with Pets In Need, she wrote.

McCurry, who had been working with Palo Alto Animal Services for years before Pets In Need took over, marveled in her April 1 letter at the high staff turnover in the organization and alleged "mismanagement" at the shelter.

"As a result, animals that come in with behavioral challenges are frequently euthanized or (if they are felines) pushed back into the community via TNR (trap-neuter-release) rather than socialized so they can be placed in homes,” McCurry wrote.

During the council's June 12 discussion, Mayor Lydia Kou alluded to the allegations in the public correspondence and asked Pets In Need staff to respond to the allegations.

"How much effort is placed to train or retrain a pet dog or cat before euthanizing?” Kou said. "There has been a lot of communication in the public, and I think I want to get to the bottom of that and understand it.”

Birdsall cited the shelter’s high live-release rate and described the process that the nonprofit employs for determining whether euthanasia should be pursued.

In such cases, Pets In Need consults with its behaviorist, Dr. Jeannine Berger, who advises the organization on possible medical interventions.

If the medical options do not render the animal safe to work with while keeping it cognitively active, the nonprofit then looks for a rescue organization that may accept it, Birdsall said.

If that doesn’t work, the decision gets moved to the organization’s Quality of Life Committee, which consists of six managers and directors who discuss potential outcome options.

Pets In Need also reported to the city in June that medical euthanasia only occurs in "terminal, pain-that-cannot be well-managed or failure-to-thrive cases.”

Furthermore, an animal is only euthanized when it’s a "danger to itself and/or others, and its behavior cannot be safely controlled or mitigated.”

The committee considers these factors and then determines whether euthanasia may be in the best interests of not just public safety but the animal’s welfare, she said.

"Do we have this dog that is very aggressive live the rest of its life in a cage? Is that humane welfare?” Birdsall asked.

When asked in an interview about the recent allegations from employees that euthanasia is on the rise, Birdsall suggested that their views may be based more on subjective experiences than the reality of shelter operations.

Shelter employees care deeply about the animals in their charge, and it's not uncommon to become traumatized by having to euthanize "the very animals we're trying to save."

"So instead of seeing each one as a one, you go, 'Oh, this is another. I can't do this again!' And that's very real," she said.

"So the data will tell you the reality. But a person's emotional interpretation is real because that's what they're feeling at the time."

A REDUCTION IN SERVICES?

If Pets In Need remains in Palo Alto, as seems increasingly likely, the city will have to accept higher costs and a few service adjustments.

Unlike in the prior contract, the organization would no longer have to provide veterinary services for animals involved in animal-cruelty investigations. Doing so would be at the medical director’s discretion.

It would also no longer have to provide after-hours veterinary care for stray animals.

Herb Borock, a longtime City Hall watchdog, is among those who oppose the new deal.

In a series of letters earlier this year, he argued that the mission of Pets In Need — to further the no-kill movement — is different from Palo Alto's mission to provide animal control and shelter services for the local community and partner cities.

"The proposed term sheet would provide more money to Pets in Need to perform less of the services the City of Palo Alto is required to do by the state," Borock wrote in late March.

Others believe the organization should be more hospitable to animal owners outside the area.

The proposed agreement commits Pets In Need to one low-cost vaccination clinic per week.

But Denise Salle, a Mountain View resident who works with numerous cat and dog rescue groups and who briefly worked at the Palo Alto shelter in 2000, believes the city should demand that the agency expand its spaying and neutering services for animals from low-income households.

She said she was disappointed to see the organization temporarily suspend its low-cost spay and neuter services shortly after it took over the Palo Alto operation — a service disruption that was extended because of COVID-19.

The service is now back, but with various restrictions. Pets In Need offers spay-and-neuter services only to Palo Alto, Los Altos and Los Altos Hills residents, though low-income residents from other communities in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties can also schedule appointments.

When Salle tried to make an appointment, she was told she would have to wait between a year and 18 months, she said. (Under the new contract, residents of Palo Alto, Los Altos and Los Altos Hills would be able to get an appointment within one month for spay or neuter services.)

"The original contract that PIN signed was to produce duplicate services of what Palo Alto Animal Services was providing to the community,” Salle said.

But now, she said, it’s increasingly difficult for pet owners to get their pets fixed.

"The big thing is that I can afford to go to the vet and pay between $600 for a male cat and up to $1,200 for a female, but a lot of people simply cannot,” she said.

Pets In Needs executives believe the service changes in the proposed contract will be barely noticed by the community.

After-hours care is already contracted out to other area organizations like MedVet and SAGE Compassion for Animals; the only difference is that under the new deal it will be the city rather than the nonprofit that's picking up the tab, Toller Gardner said.

Animal cruelty investigations, meanwhile, are extremely rare in this area. Birdsall said there hadn't been any in her year at Pets In Need.

But when they occur, they tend to be disruptive to normal shelter operations and they require a very specialized skill set, which makes this task suitable for contracting out.

"Because all of the medical care that we provide throughout the week, it is very highly scheduled for in-shelter animals, and for community animals," Toller Gardner told this publication.

"If we need to then interrupt that during an investigation, which is very time-consuming and labor intensive, it throws things off and really backs up all of the care for the in-shelter animals and the community animals."

Despite some concerns from animal control officers and members of the public, council members unanimously agreed at their June 12 meeting that the city should stick with Pets In Need.

The in-house proposal would have required wholesale changes to the operation, which was something the council showed little appetite for.

And the city’s past attempts to solicit animal service providers only reinforced the shortage of alternatives: In each case, Pets In Need was the sole respondent.

Closing the shelter and outsourcing animal operations to another shelter is also a tough political sell. The East Bayshore Road shelter, for all its deficiencies, has always been popular.

When the city auditor’s office surveyed residents in 2015 as part of its audit, 80% of the residents and Palo Alto Animal Services customers said it was "essential” or "very important” to have a local shelter that provides services such as animal control, animal cruelty investigation, vaccinations, spaying and neutering.

During the June 12 discussion, Council member Ed Lauing went as far as to suggest that the recent changes in Pets In Need staffing aren’t necessarily a bad thing, particularly given all the problems that had previously been reported.

The organization, he asserted, has "righted itself."

"We’re starting off with a whole new management team, from the CEO all the way down. If the management team also did terminations or changes, that’s also a good thing. We should feel comfortable about that,” Lauing said.

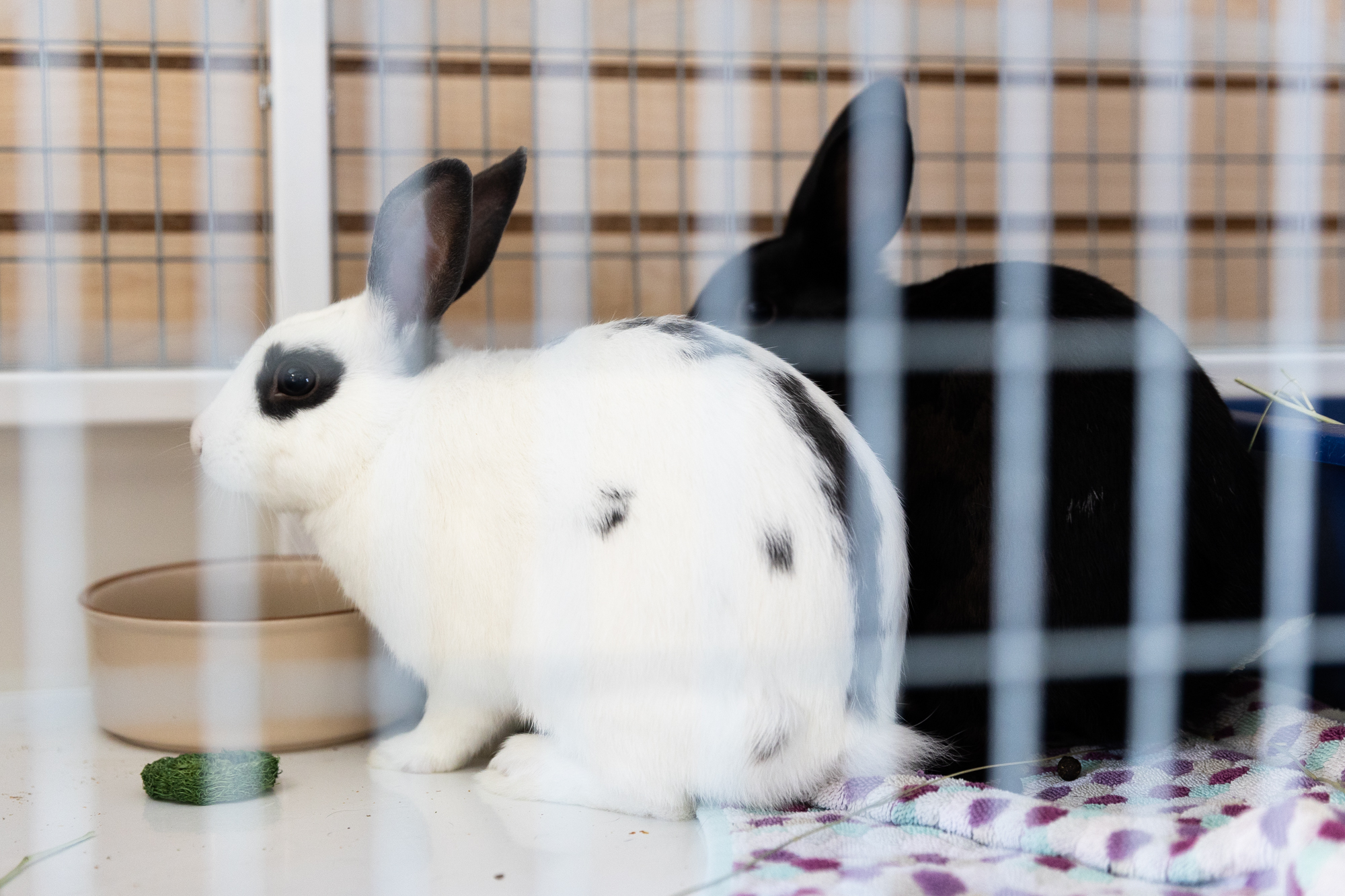

Pets In Need, meanwhile, is looking to grow further. The proposed contract commits $2.5 million in city funds for shelter renovations, including a new cat room and space to relocate the rabbit cages that currently greet visitors (and occasionally unnerve passing dogs) near the shelter entrance.

Toller Gardner said the organization is also looking to "further professionalize the organization at all levels."

It's no coincidence that after a sequence of executive directors, she is the nonprofit's first CEO. The job title, in a way, is a signal to Silicon's Valley donor community that Pets In Need is a worthy investment, she said.

She noted, however, that when it comes to winning over the people of Pets In Need, her actions will carry more weight than her title.

And she has already taken one step to correct an action that she said she wished hadn't happened. After informing Rosten in April that the organization will be coming to pick up Jasper and Brodie, Pets In Need sent a follow-up letter last month rescinding the decision.

Toller Gardner informed Rosten in the July 12 letter that the dogs appear to be "flourishing under your direction" and that the organization wants to formally complete the adoption process for the two dogs.

When asked about the change in directions, Toller Gardner said that at the time of the initial letter, the organization hadn't done enough research on the situation to determine good alternatives.

After subsequently learning that Rosten has "essentially adopted them," Pets In Need decided to formalize the arrangement, she said.

Rosten still isn't thrilled about having the funding cut off and suggested that the organization effectively "abandoned" the dogs with her. But she said she loves both dogs and is happy that they're staying.

Toller Gardner, for her part, is confident that she can break through the tension and get the entire Pets In Need workforce united behind the organization's mission.

"I believe in the goodness of the people here. The fact that they are called to do this work speaks volumes about them and it means that they are compassionate people who really want to make a difference for animals," she said.

"I believe that over time, they're going to see that I'm right there with them. And that is what will build trust. My title is unimportant. It's what they see me doing day in and day out.

"And when they have seen that long enough, they're gonna say, 'She's one of us.'"

Comments