Forty minutes. That's how long it took Laura* to walk from her home to her high school two blocks away one sunny April morning.

Getting to the classroom has been a struggle for students like Laura, 15, who just finished her freshman year at East Palo Alto Academy (EPAA). She has had heart palpitations and difficulty sleeping since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Her anxiety is worse on days when her best friend won't be at school. She was absent from one class 28 days during the 2022-23 school year. The Almanac agreed not to publish Laura's real name, to protect her privacy.

In the past, Laura's mother Yadira Mederos De Cardenas, a preschool teacher at All Five in Menlo Park's Belle Haven neighborhood, would have called in Laura's absence to the high school. But having already missed so many work days this past school year — about a week per month of work to care for her children — she put her foot down.

"I said, 'Sorry your friend is not here; I'm going to drop you off, and I can call the counselors and let them know what happened, and you can do classes in the office,'" said Mederos De Cardenas.

For a long time, test scores have slumped at schools in the area, which lies in the shadow of Stanford University and neighboring wealthy Silicon Valley school districts on the other side of Highway 101. But last school year, something else concerning happened: there was a huge jump in the number of students who weren't coming to school at all.

Laura is among the skyrocketing number of students in the East Palo Alto area over the last two years who have been chronically absent, which the state defines as missing 10% or more of the school year. The state began collecting and publishing chronic absenteeism data from schools during the 2016-17 school year.

East Palo Alto Academy, a small charter high school, saw a chronic absenteeism rate of 199 out of 355 students (56%) during the 2021-22 school year, according to state data. Numbers improved this school year, with 111 of 290 (38%) students chronically absent as of mid-May, according to Sequoia Union High School District data.

The Ravenswood City School District, which has about 1,600 students in its elementary and middle schools (excluding charters) in East Palo Alto and Menlo Park, saw chronic absenteeism spike from just 471 out of 2,549 (18.5%) during the 2018-19 school year to 846 out of 1,637 students (51.7%) in 2021-22.

Absences, whether excused or not, count toward chronic absenteeism figures. Transitional kindergarteners aren't included in state statistics.

It's not just a problem in the Ravenswood district. Chronic absenteeism has ballooned statewide since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 30% of California students counted as chronically absent during the 2021-22 school year, up from 10.1% during 2018-19. Still, East Palo Alto-area numbers are well above the state average.

Chronic absenteeism numbers in Ravenswood have slightly improved to 40% this school year, according to a June 22 district staff report.

The schools serve an especially diverse, low-income area of the Bay Area. Some 86% of students in the Ravenswood district during the 2021-22 school year met the definition of socioeconomically disadvantaged, which means that they are eligible for free or reduced priced meals or have parents or guardians who did not receive a high school diploma. Nearly 47% of district children have experienced homelessness. At EPAA, 81% are from low-income households.

How missing school impacts students

Students miss out on foundation skills that impact them forever when they miss school, including learning to socialize with their peers, said Sara Stone, Ravenswood's assistant superintendent of teaching and learning.

"When students are chronically absent, no matter what the issue is, you're missing out on learning," she said. "School is about giving kids the keys to the locks that are going to be in front of them in their lives."

Children who are chronically absent in preschool, kindergarten and first grade are much less likely to read at grade level by the third grade, according to U.S. Department of Education data. Students who cannot read at grade level by the end of third grade are four times more likely than proficient readers to drop out of high school, according to the Department of Education.

Alex said that students who are chronically absent "very easily fall behind."

"Considering in the district that a lot of students are behind in reading level or math level, it's very easy for them to fall behind even more. A lot of students are behind by multiple grade levels."

Just 6% of students met or exceeded the math standards in 2022. Only around 12% met or exceeded the English language arts (ELA) standards.

Students performed better in 2019, with 18% meeting state standards for ELA and just under 12% meeting standards for math. In 2018, scores were higher still, with 24% of students meeting ELA standards and 15% meeting math standards.

Ravenswood board Trustee Bronwyn Alexander told the board in June that when absenteeism rates are this high, it is going to directly reflect in test scores.

Why kids are missing class

The Ravenswood district does not keep a detailed database on the causes of students' absences, which is similar to other districts in the area contacted by The Almanac. Instead, missed days are recorded and marked as excused or unexcused. Notes on absences are kept within individual student records, but the districts do not keep such notes consistently.

The Almanac requested absence notes, but Ravenswood officials declined, saying it would put undue burden on its staff and would violate student privacy, despite The Almanac requesting that any identifying information be redacted.

Ravenswood district officials attributed the increase in absences this past fall and winter to the so-called "tridemic" of RSV, flu and COVID-19, especially among young children. School officials are have encouraged students to not come to school when they feel sick so they don't expose other students.

"Obviously our target is that every student comes to school regularly and no students are chronically absent, but in this world in which we're living, we want our students to feel safe, healthy and secure," Jennifer Gravem, executive director of Educational Services with Ravenswood City School District, said this past winter.

Pre-pandemic, illness was always the top reason for student absences, said Emily Bailard, CEO of EveryDay Labs, a Redwood City-based startup that helps schools nationwide reduce student absences and has worked with the Ravenswood district. Sickness still only accounts for about half of absences at schools her organization worked with this past school year.

"Portraying absences simply as illness-related is missing half of the picture," she said. "Particularly this year, as school policies around COVID or illness are a lot less strict."

Ravenswood Superintendent Gina Sudaria concurs that there are many reasons for student absences.

Sudaria said the district plans to spend this summer finding the root cause of why students have been chronically absent from classes.

"We are always constantly trying to build a stronger school culture," she said. "In reality, we also don't want kids coming to school sick because of COVID. We don't want perfect attendance anymore. We do want to be mindful of their mental health issues."

Students are feeling more socially anxious than before lockdown, according to Stone. School officials are working to help them, including allowing students to go to quiet spaces for breaks, and to be a "tiny bit" late to school, rather than punishing them for not being on time. They are also working with families to designate a trusted adult for students to talk to during the school day.

"We as a society got scared to be in public together because of our health," Stone said. "It's a valid thing. We potentially instilled more fear in them (children) than was necessary."

Bailard said mental health challenges are manifesting into higher rates of anxiety, which leads to school refusal — defined by the Children's Health Council as repeatedly balking at attending school or staying there.

There are also affluent families who feel more willing to pull their child out of school for a vacation, or trips to visit family to make up for what kids missed out on during the pandemic, she said.

"The norms around going to school and acceptable reasons to miss school have just fundamentally shifted," Bailard said.

EPPA Principal Amika Guillaume said students at her school who perpetually miss classes are struggling with their mental health or family challenges. There are also students juggling school with 30 hours or more of work per week to help their families pay rent.

Aside from illness, adults who are struggling with their own mental health or other illnesses have trouble bringing their kids to school, said Alex*, who works in the Ravenswood district but asked to not be named to protect her job.

"Some (students) are disappointed and acknowledge the fact they are falling behind," Alex said. "It's tough to see from the perspective of, I'm there to support them and they don't really have a lot of control over (missing school)."

San Mateo County Health clinics report an increase in clients being referred for anxiety and depression since the pandemic hit, according to Douglas Fong, a clinical services manager for San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services who oversees the East Palo Alto Community Counseling Center.

Unreliable transportation can also be an obstacle for getting to the classroom. Gravem recounted a case in which the days a student was missing were the ones when they weren't at home and were staying with an uncle.

Effects of the pandemic and other challenges

The East Palo Alto-area was hit particularly hard by the pandemic. According to Sequoia Dignity Health Hospital in Redwood City, with 2,019 confirmed cases per 10,000 by January 2022, East Palo Alto had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections by far in the hospital's service area, which ranges from Burlingame south to East Palo Alto.

Experts say school officials are facing a complicated problem that doesn't come with simple solutions.

Gravem of Ravenswood said the state needs to reevaluate its definition of what it means to be chronically absent. It's hard to send the message of "stay home if you have COVID" while also saying "you have a chronic absenteeism problem," she said.

The district can't measure the trauma students experienced from losing family members, seeing their parents lose jobs or worrying about risks undertaken by family considered essential workers during the pandemic, said Ravenswood school board President Jenny Varghese Bloom in September 2022.

"We can not quantify how many of these kids were taking care of siblings or watching TV all day because no one was there to take care of them," she said.

But it's more than just the pandemic. East Palo Alto faces other challenges that contributed to absenteeism.

In February, prolonged power outages affected some residents of East Palo Alto, who were left in the dark for 48 hours during a winter storm that brought freezing temperatures and rare snow to nearby higher elevations. Two schools in the city were forced to cancel classes because they were without power.

Despite the challenges, there's also a palpable sense of pride in those who come from the tight-knit community. A school board member went door-to-door to hand out gift cards, blankets and power packs to the elderly and most vulnerable during the outage.

In many ways, this attendance crisis is coming at a moment of transformation for the Ravenswood district. Some schools, without central air conditioning, air filtration systems, and lacking ADA compliance, are getting their first updates since the 1960s thanks to bond financing. Yet students are still not coming to class.

Inequality exacerbates absenteeism

Ravenswood and EPAA's chronic absences exceed state and local averages.

Menlo-Atherton High School in Atherton has a mix of low-income and wealthy students and its chronic absenteeism rates were lower during the 2021-22 school at 23.4%.

These disparities may be explained by the different demographics. Socio-economic status is one major factor that experts say impacts school attendance. The Ravenswood district hosts the most low income students in Silicon Valley.

Rates of chronic absenteeism were much lower in nearby districts with lower poverty rates. In Las Lomitas Elementary School District, just 6.6% of students are low income; 9.6% of Menlo Park City School District students are low income, and 10.1% are low income in the Woodside Elementary School District.

The road to improving attendance is long for low-income students, said Bailard.

"For (chronic absenteeism rates of) 30% to go to 25%, to go to 15%, it took years pre-pandemic," Bailard said. "At a district (level), it's hard to move more than two to three percentage points in a year."

She noted that a typical student who is chronically absent is facing an average of five or more barriers to attendance, including unreliable transportation, illness, unstable housing, and lack of sleep or access to food. If you address one barrier, like transportation, most students are still facing four other barriers, she said.

Students who are more affluent face fewer overall barriers to attendance and their attendance rate has bounced back more quickly, Bailard explained. They are less likely to grapple with access to food, housing, transportation or medical care.

"We can't close the achievement gap if we don't close the attendance gap," Bailard said. "Students are behind from the pandemic. We're going to have a really hard time accelerating their learning if the same students who are behind are missing (school) 10 to 20 to 30% of the time. You can provide all the tutoring, but it's not going to be effective."

On-campus tutors through Ravenswood Classroom Partners provide mentorship to students, but if children are missing a large chunk of the school year, like 100 days, it's going to be really hard to make up for lost classroom learning, Sudaria acknowledged.

Need for more mental health resources

Nearly a third of Silicon Valley's middle and high school students reported experiencing chronic sadness, and one in eight report having considered suicide, which is alarmingly high, according to the 2023 Silicon Valley Index, which measures the region's economy and community health.

In 2020, at 16.2%, East Palo Alto had the highest rate in the county of residents who said they struggled with poor mental health for two weeks or more over the last month, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mederos De Cardenas said EPAA offers few mental health supports to her daughter and her family can't afford to pay for therapy.

She herself has always struggled with anxiety and panic attacks, but it's gotten worse since the pandemic, she said. She contacted three different therapists but couldn't afford them so she has a monthly therapy session with her psychiatrist instead.

EPAA Principal Guillaume acknowledged the shortage of therapy services.

Still, the charter high school is better resourced than others. There are two psychiatry fellows and three therapy interns from Stanford who work part time on campus. The school also has a full-time social services manager.

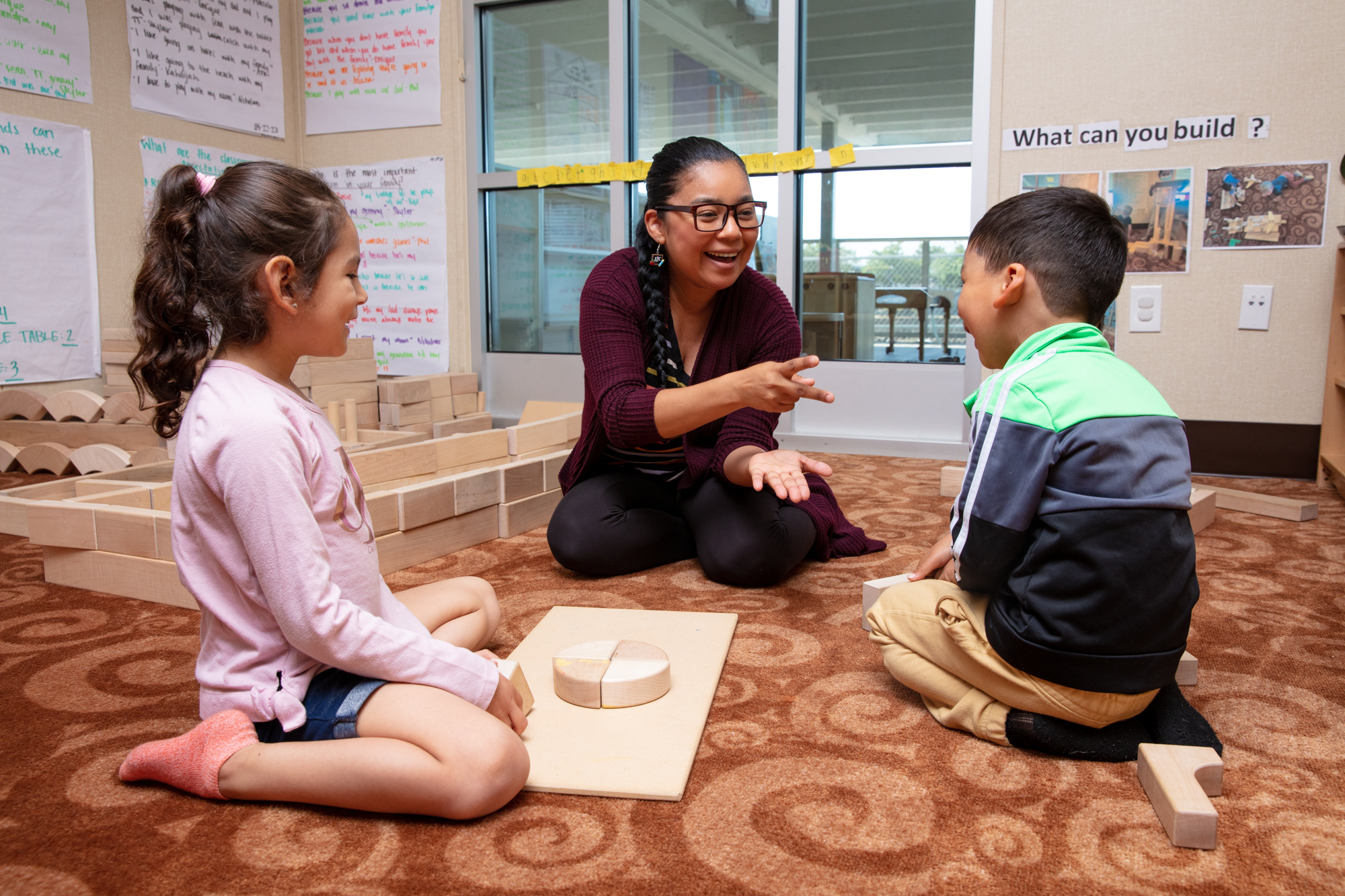

All Five Executive Director Carol Thomsen said her early childhood learning center, which is next to Ravenswood's Belle Haven Elementary School, is unique in that it has a counselor available to staff and families onsite on Mondays through One Life Counseling Center.

"It lessens the stigma," said Thomsen. "It's the best we can do for now. Unfortunately, they (the counselor) don't speak Spanish."

The state itself is facing a shortage of behavioral health workers. A 2018 report by the University of California at San Francisco predicted — even before the pandemic increased need for such services — that by 2028, demand for mental health providers would be 40% higher than supply.

Cultural barriers to mental health care

Stigma around talking about or seeking treatment for mental health struggles is an ongoing barrier for care in the Ravenswood community, said Fong of San Mateo County Health.

Alex, who works in Ravenswood district classrooms, said she works with a lot of students who come from families of color where mental health is not discussed.

Ethnic minorities tend to access mental health services at a much lower rate than their white peers, according to 2009 research. Latinos have been found to be about half as likely as white men and women to access these services when they need them, according to a 2018 national survey.

Vigilant behaviors learned during the pandemic are also contributing to absences. Mederos De Cardenas said she continues to follow quarantine policies put in place during the pandemic. Even if her 4-year-old Nicolas isn't feeling sick, she keeps him home if one of his siblings is ill, to protect his classmates in case he's contagious but isn't showing symptoms yet.

"It's something I'm working on, thinking about in the future if I should send him," she said. "My feelings were different before the pandemic." As a teacher, she said she calls parents to find out about a student's illness and would not say, "Don't bring them in" if their siblings were sick and they weren't.

She said in Mexican culture it's the mother's responsibility to take care of children.

"I'm more informed about my culture and working on the way I was raised," Mederos De Cardenas said. "I have this job that I tremendously love and I don't want to lose it."

She said she's also pulled her children out of classes during the school year to travel to Mexico to see family, especially since her father died four years ago. She now only plans to travel to Mexico during the school year for emergencies.

"I want to be a role model," she said. "The situation (absences) is impacting my two children at school — I regret it and being home with them. ... There's just this trauma from the pandemic."

In Part II of this three-part series, we take a closer look into how mental health struggles for both students and their parents and guardians can impact attendance.

About this story: This is the first of three stories in a series exploring why chronic absenteeism has spiked in East Palo Alto and Menlo Park's Belle Haven neighborhood. The series was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship with the support of EdSource editor Dympna Ugwu-Oju. Upward Scholars' Brenda Graciano translated the report into Spanish. Embarcadero Media Visual Journalist Magali Gauthier translated the photo captions.

Comments

Registered user

Monta Loma

on Jul 19, 2023 at 8:43 am

Registered user

on Jul 19, 2023 at 8:43 am

What an interesting article and very informative. I had no idea...