For decades, Santa Clara County and Stanford University have operated under an understanding that any growth proposals by the university should steer clear of the foothills.

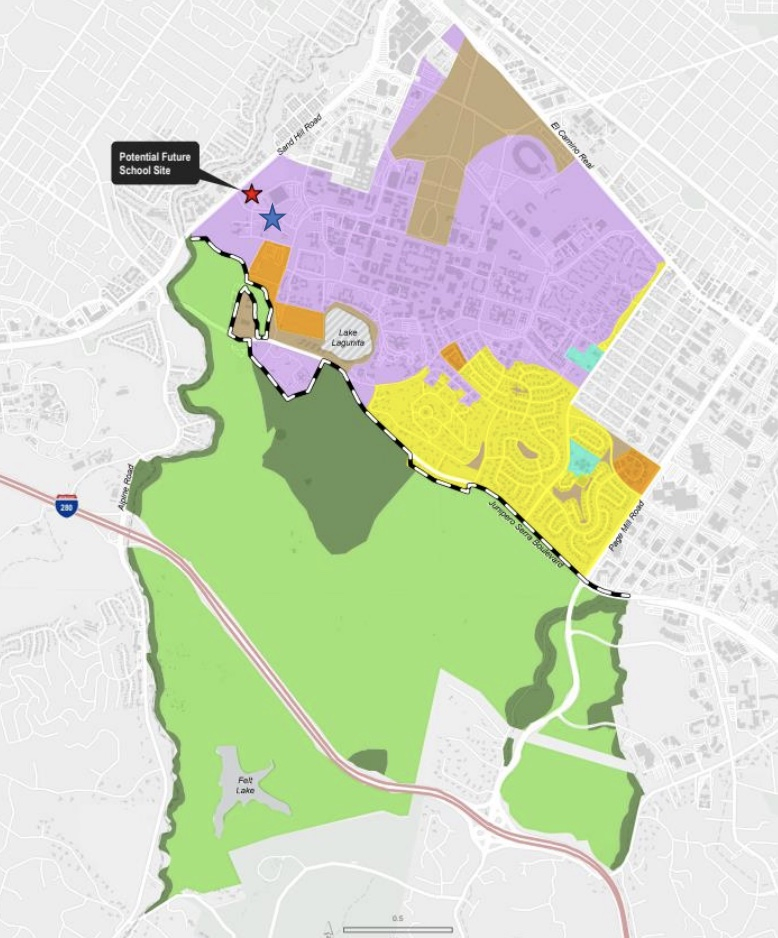

The policy is enshrined in Stanford Community Plan, a document that the county approved in 2000 and that governs the university's land use policies. Under the plan, new development at Stanford is generally confined to the area within the university's "academic growth boundary," which surrounds the main campus and which pointedly excludes open space preserves west of Junipero Serra Boulevard.

The boundary, however, is somewhat porous. The Stanford Community Plan had only established it for 25 years, which means it is set to expire in 2025. It creates exceptions for field research; for small, specialized facilities that support existing activities in the foothills; and for uses that "require a remote or foothill setting for their functioning." It also allows the Board of Supervisors to allow additional exemptions if four of the five supervisors support this development.

While Stanford and county have tussled at length over the university's growth plans in recent years, open space has generally been a topic of consensus. When the university applied in 2016 for a general use permit that would add 3.5 million square feet of development, it avoided any growth in the foothills as part of the proposal, which was withdrawn in 2019.

That consensus, however, is now facing its biggest test since the academic growth boundary (AGB) was established. The county is now updating the Stanford Community Plan and as part of the effort, county officials and consultants are proposing to retain the boundary for 99 years. Members of county's Planning Commission on Wednesday gave their informal endorsement to the policy, which will be vetted by the Board of Supervisors later this year. Stanford, for its part, is arguing that 99 years is far too long a duration and is requesting more flexibility.

The university laid out its objections in a Tuesday email from Diana O'Dell, its director of land use planning. O'Dell cited guidance from the state's Office of Planning and Research, which identified 20 years as a suitable long-term planning horizon for general plans. Imposing a 99-year moratorium on development outside the academic growth boundary would be "inconsistent with any realistic planning horizon for the Community Plan," she wrote.

"As indicated by OPR's guidelines, it is not possible to predict with any sort of certainty the needs of the community, the university, or society at large 99 years into the future," O'Dell wrote. "Looking beyond a realistic planning horizon suffers from the unpredictable nature of future conditions that may affect land use policies: climate change, new technologies, economic uncertainty, changes in federal education and research policies, and evolving modes of education."

She also argued that a future Board of Supervisors may find housing projects or "transformative academic facilities" outside the academic growth boundary appealing. As such, it should have discretion to approve such projects "if the public benefits are significant enough." She recommended giving county officials discretion to modify the boundary in cases where public benefits "outweigh any anticipated negative aspects of AGB expansion."

The argument didn't seem to sway the planning commission, with several members saying they would support the extension of the academic boundary beyond the current 25-year horizon. Consultants from M-Group, which is working on the plan update, noted that the policy helps ensure compact development and conservation of natural resources.

Commissioner Vicki Moore said adopting a 99-year time frame would be appropriate and cited a study that the county commissioned in 2018, which showed that Stanford has significant room to grow within its campus without encroaching into the foothills.

"I know that the 99-year time frame is very important for a variety of reasons, especially since the GUP (general use permit) process allows significant flexibility and significant increase in intensity of development on the campus," Moore said.

Others noted that existing rules already provide Stanford with flexibility on building in the foothills. Alice Kaufman, policy and advocacy director at Green Foothills, a conservation nonprofit, urged the commission to support stronger policies on limiting development beyond the academic growth boundary.

"Stanford's objections based on requiring more flexibility don't make sense," Kauffman said. "There's nothing preventing a four-fifths vote of the Board of Supervisors from changing the academic growth boundary based on its finding."

In fact, the board may not even need four votes to make the change. Commissioner Marc Rauser observed that while the policy requires four votes to approve growth beyond the boundary, it would take only three votes to change this policy and lower the threshold. The fact that a simple majority can modify or abolish the policy is a major flaw, Rauser said.

"I think it's important, for lack of a better term, for politicians to have something to feel good about, but I think the way it is done, I think it's sort of ludicrous," Rauser said. "I will vote for it, but in my mind it doesn't really mean too much if they can literally just change it with a majority vote on it."

Kaufman also said she was concerned about the "fundamental inconsistency" in the process, which allows a simple majority of the board to eliminate protections for open space preserves. She suggested that the county explore ways to address this issue, possible through a ballot measure.

As part of the update, the county also plans to revise a host of policies related to housing and transportation. This includes requiring Stanford to construct most of its new housing either on or next to its campus in order to reduce the impact of its growth on neighboring cities, most notably Palo Alto and Menlo Park. M-Group is also recommending that the county eliminate an existing policy that allows Stanford to pay an in-lieu fee rather than construct housing that would otherwise be required as part of an expansion of its academic facilities.

And while the county intends to retain the existing "no net new trips" mandate for Stanford, M-Group is recommending adopting a more stringent standard for measuring traffic levels. Rather than focusing exclusively on the peak commute hours in the morning and afternoon, the county would now consider three-year periods. It would also factor in reverse commutes.

Stanford has urged the country to steer away from "trip-based metrics," which it claims will make "compliance costly and time consuming for both the County and Stanford and, ultimately, penalize Stanford for intensifying infill development near transit, jobs, and schools," according to an email that Erin Efner, Stanford's associate vice president for land use and environmental planning, submitted to the county earlier this month.

Efner also requested that the county consider giving Stanford more flexibility to build housing outside its core campus. Constraining future housing solely to the core campus and contiguous lands "precludes providing housing in communities where actual demand exists," she wrote.

"Increasing geographic flexibility, in particular in transit-rich areas outside the immediate Stanford area, creates additional opportunities to address the regional housing shortage, is consistent with VMT (vehicle miles traveled) and greenhouse gas reduction plans, and better reflects Stanford's actual housing demand and increasing hybrid workforce," Efner wrote.

Comments