There was a time, not too long ago, when gunshots and the drone of court hearings played like a soundtrack to Prince Wilson's life.

In 2011, his son Adam died after a shooting in an Oakland bar. Two years ago, his other son was shot in the leg. When the son's friend helped him to the car and the two drove away, a gunman shot and killed the friend at 98th Street and MacArthur Boulevard, Wilson said.

The personal tragedies and Oakland's climate of violence took their toll on Wilson, 65, and his family. He and his wife divorced after Adam's murder but got back together two years later. They split again after the more recent shooting.

A U.S. Army veteran who was born and raised in Oakland, Wilson needed to get away, but his options were limited. He moved to Modesto and found shelter in a complex for individuals with disabilities, where he spent six years before the place was shut down because of building code violations, he said in an interview. He crashed on couches, lived in his car and moved in with his brother for a month before finding shelter in San Jose through the nonprofit LifeMoves in early 2021. That helped, but it was, at best, a temporary solution.

His housing instability was compounded by health issues. Wilson, a custodian with the Oakland Unified School District, retired in 2006 after suffering a stroke that weakened the left side of his body. More recently, he had two throat surgeries and a heart surgery to replace five valves, he said.

But things turned around last May, when Wilson became one of the first tenants at Arroyo Green, a newly constructed 117-apartment complex in downtown Redwood City. Developed by the nonprofit MidPen Housing, Arroyo Green is part of a residential boom that has brought more than 4,000 new residential units to Redwood City since 2015.

Now Wilson, in addition to going to occupational therapy, physical therapy and volunteering at VA Palo Alto Healthcare Systems, has another routine: visiting the building's game room in the evening, putting on some Al Green music and working on his pool shot. "I like to see if I still got it," Wilson recently told this news organization.

Arroyo Green welcomed its first residents in March 2021. When Wilson arrived two months later the hallways were mostly empty, the common areas were quiet and the parking garages full of vacant spaces, he said. Gradually, more people moved in and the place became more vibrant as common spaces that were restricted during the pandemic began to open up to the tenants.

He recalled an incident last month when he was taking out the garbage in his electric mobility scooter and a woman in her 80s came up to him, grabbed his hand and asked him if she could help him — a gesture that surprised and delighted him. On the weekends, he sometimes rides his electric scooter downtown to shop or check out the outdoor bands.

"There's a lot of stuff for families and kids to do," Wilson said in late April. "It's different from going to sleep with gunshots in Oakland to coming here where it's so quiet that I can't sleep."

Mary Romanola, who moved into Arroyo Green in June 2021, also credits the new development with saving her from a precarious situation. Shortly after retiring from her job as an adjudicator for unemployment, Romanola, 66, found herself unable to afford rent. She and her daughter initially moved in with her mother. When her mother had to be placed into a retirement home, Romanola moved in with her ex-husband. The situation, she said, was a "nightmare." During the turbulent period, which was marked by visits from social workers and nurses, Romanola learned that she qualified for an apartment in Redwood City.

"I cried when I walked in here," Romanola said in an interview in her apartment. "My girlfriend was with me and I said, 'Finally!'"

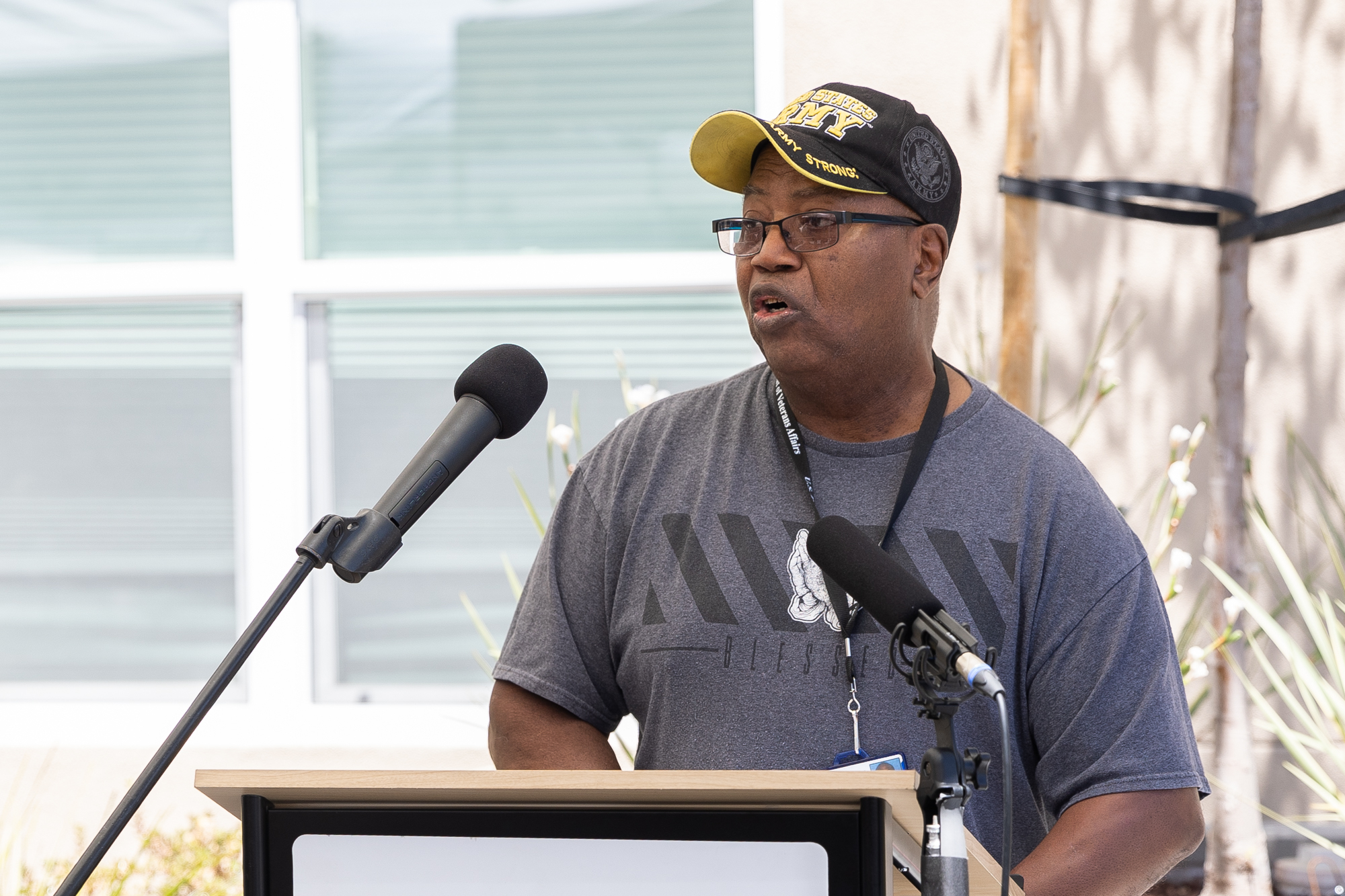

Last month, Wilson joined dozens of housing advocates, MidPen Housing leaders and Redwood City officials for the delayed grand opening of Arroyo Green. Recalling his personal experiences, he said the move to Arroyo Green changed life for the better. He said he lives by the adage, "Walk by faith, not by sight."

"I walked by faith to my new apartment," Wilson said.

The rise of the precise plan

Faith may have brought Wilson to Arroyo Green, but it took a lot of planning to bring Arroyo Green to Redwood City.

And no city planning tool has been as instrumental in the creation of this project and the many other residential developments that have recently opened up in downtown Redwood City than its Downtown Precise Plan, a document that the City Council approved in 2011 and that over the past decade helped turn the city into a regional leader when it comes to housing production.

Redwood City Mayor Giselle Hale told the assembled crowd during the May 25 event at Arroyo Green that the city currently has 1,200 new affordable units in 22 developments that are either under construction, approved or proposed. She also noted that within a block of Arroyo Green there are 900 new and proposed housing units, which include senior housing, apartments for extremely low income individuals, market-rate housing and workforce housing.

"Arroyo Green is a true example of collaboration, innovation and long-range planning in government," Hale said.

Redwood City is one of many cities on the Peninsula and around the Bay Area that are relying on precise plans — or their slightly more prescriptive cousins, specific plans — to transform their downtowns. Such plans promote a desired vision for a particular area of the city by creating a specific set of zoning rules and development standards. Any projects tailored to meet these standards gets on the fast track toward approval.

In 2012, a year after the Redwood City council approved its vision document, Menlo Park passed its own downtown specific plan, which focuses on El Camino Real and Santa Cruz Avenue. Some of the biggest and most ambitious projects in the city's development pipeline, including Stanford University's Middle Plaza at 500 El Camino Real and the Springline development at 1300 El Camino Real, were either sparked by the downtown plan or reshaped because of it.

"We're starting to finally experience the renaissance that people have wanted in our downtown," Menlo Park City Council member Ray Mueller said during a recent interview about the 2012 downtown specific plan.

The city of Mountain View has embraced specific plans with particular gusto. It approved its downtown plan in 1988, and city officials credit it with transforming Castro Street into the vibrant, pedestrian-friendly destination it is today. These days, Mountain View staff are revising the plan to enhance historic preservation, refine design rules for new developments and ban administrative offices such as tech headquarters from taking up ground-floor retail space along a portion of Castro, a change designed to attract more retail and, in the parlance of city planners, "activate" the street.

After that, the City Council plans to take a broader look at the downtown plan and consider more significant revisions, including potentially ways to encourage the construction of housing, Mountain View Mayor Lucas Ramirez told this news organization.

Palo Alto, which has been far more cautious than its neighbors when it comes to growth, is an outlier by not having a long-range plan specific to its downtown area. While its land-use bible, the Comprehensive Plan, calls on the city to "evaluate developing a specific or precise plan for the downtown, California Avenue, and El Camino Real areas," the City Council has been in no rush to put that program into effect.

The city is, however, now considering moving ahead with a more constrained version of a downtown specific plan, which would focus almost exclusively on housing. The city just received an $800,000 grant from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission to move ahead with the planning effort, which Palo Alto city staff estimates will take about three years to complete.

Area plans — whether precise or specific — are far from new. The planning tool was developed in the late 1970s, when California was growing and state officials were looking for ways to construct more housing, discourage sprawl and enhance public amenities such as transit and retail in city centers.

In 1978, the state released a document titled "An Urban Strategy for California" that established new policies for specific plans, including exempting developments that meet the standards of these plans from the stringent review requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The CEQA exemption, the document states, "will speed construction and thereby help reduce housing costs."

The tool took on new powers in 1984, when California adopted a law specifying that any residential project or zone change that is undertaken to implement — and is consistent with — a specific plan for which an environmental impact report has been certified is exempt from the provisions of Division 13, which governs environmental reviews. In effect, it helped speed up the approval process for developments compatible with city plans.

The mission outlined in 1978 remains as urgent today, as California wrestles with a gaping housing shortage and local municipalities find themselves facing state mandates that require them to boost their residential development or risk losing land-use powers. For many cities, precise plans are a key to meeting the housing targets spelled out by the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA).

That, in itself, represents a shift. Aaron Aknin, who worked as planning director in Palo Alto and Redwood City and who is now principal and co-owner of the land-use consulting firm Good City Company, said that a decade ago, when Redwood City was adopting its plan, its big focus was to revitalize the downtown. City leaders were open to allowing commercial and mixed-used development in the early phase of the plan so that this growth could support housing in the plan's later phase.

Here and elsewhere, downtown specific plans serve as tools to generate more residential construction.

"It's structured that way because of RHNA allocations. ... You need places to put your (residential) units, and downtown seems like a pretty logical place," Aknin said.

When it comes to Arroyo Green, the city's downtown specific plan accomplished exactly what the state's 1978 document had envisioned. Andrew Bielak, associate director of housing development at MidPen Housing, said the organization was able to go through Redwood City's formal entitlement process in just six months, including approvals by the city's Planning Commission and Architectural Advisory Committee. It broke ground on construction in 2019, and tenants began to move into the complex in March 2021.

The existence of the specific plan made the city-owned site at 707 Bradford St. appealing for MidPen Housing because it made the planning process predictable, Bielak said. MidPen Housing knew exactly what type of building category it would fit into under the plan and which guidelines it would have to follow to get the city's approval, he said.

"We knew the city was committed to ensuring that this had a planning process that could be streamlined, that would allow us to proceed on a timeline that would make it happen quite quickly in the affordable housing world — relatively quickly in any development world," Bielak said. "It was definitely a fast process, and the Downtown Precise Plan definitely was significant in that."

Redwood City: A residential boom

As far as downtown specific plans go, Redwood City's is particularly broad and ambitious, touching on everything from housing production and historical preservation to transportation improvements and economic vitality.

Its main goal, according to the plan, is to "restore downtown as the indispensable hub of the city where a mix of diverse services, conveniences, experiences and lifestyle choices are provided in a way that preserves downtown's rich supply of historic resources, while remaining appropriate to the social and economic conditions of life in the 21st Century.

"The community intends to create a visually appealing and memorable urban district that is the primary iconic image that stands for Redwood City," the plan states.

Arroyo Green is one of eight Redwood City projects that have already been completed under the Downtown Precise Plan, which caps new development in the downtown area at 2,500 residential units, 574,667 square feet of commercial space and 100,000 square feet of retail. Three more projects are under construction, according to the city, while nine others have been proposed and are awaiting approval.

The projects vary in size and type. The biggest builder in the downtown area is Greystar Development, which received the go-ahead to construct two eight-story residential developments at 1305 El Camino Real and 1409 El Camino Real that between them include 487 apartments. The company also received the green light for a seven-story residential development with 175 housing units at 103 Wilson St., a project that involved merging seven parcels into one lot.

Other completed projects in the Downtown Precise Plan area include a five-story office-and-retail building at 815 Hamilton Ave. at the rear of Fox Theatre; an eight-story office building at 601 Marshall St. and a four-story development with two stories of retail and two of office space at 2075 Broadway.

While the downtown boom in Redwood City unfurled relatively quickly, the plan that made it possible was several decades in the making. City leaders planted the seeds for the downtown plan in 1998, when they created a task force composed of residents, businesses and property owners charged with developing a new vision for what was then a sleepy downtown with few options for food or entertainment. City Council member Jeff Gee, who served on the city's architecture review committee back then and who became involved in the effort, said there weren't many reasons for people to stop in downtown Redwood City. Most people just drove through it.

"The group wanted Redwood City to be the Peninsula hub for entertainment: They wanted vitality and a vibrant downtown, and the City Council embraced it," Gee said in an interview.

The downtown plan that the council adopted in 2007 clearly reflected Redwood City's urban ambitions. One of its strategies is to provide "vitality, amenities and a range of entertainment, shopping and cultural offerings that suburban residents are used to finding in San Francisco or San Jose."

Another strategy calls for promoting dense housing options, enhanced public transit service and station amenities, a wide range of entertainment, cultural, retail and restaurant offerings, and a strong employment district.

Not everyone was thrilled about this vision. The council's initial attempt to advance the plan was halted in 2007, when local attorney Joe Carcione sued the city, arguing that the downtown plan had failed to adequately consider the impact of the new large buildings' shadows.

It took more than three years for the city to resolve the litigation, complete the necessary studies and formally adopt the plan. That's when construction really took off, Gee said.

"When the litigation was resolved, there was a lot of pent-up demand. Everything happened at the same time. A lot of projects came forward at the same time. A lot of construction happened at the same time.

"The result of the completion of that work is that there's an energy and vitality in downtown now," Gee said.

Menlo Park: A taste of big-city life

While residents at Arroyo Green have already settled in, the Springline development in downtown Menlo Park is weeks away from offering its first leases.

Located at 1300 El Camino, the mixed-use project includes 183 apartments, about 200,000 square feet of office space and an assortment of bars and restaurants that the developer, Presidio Bay Ventures, plans to open later this year.

Initially known as Station 1300, the project was pitched by Greenheart Development Co. and approved in 2017. In early 2020, Presidio Bay Ventures took over the project from Greenheart.

Recognizing the changing nature of workplace culture due to the pandemic, Presidio Bay has restructured the project for the new era, incorporating more flexible and outdoor work spaces, enhancing HVAC systems to improve indoor air quality and conducting a "top to bottom" revision of the floor plans and architectural elements to allow multi-tenanting in the two commercial buildings, said K. Cyrus Sanandaji, managing director of Presidio Bay Ventures.

Last November, Presidio Bay announced that the first commercial tenants would be Canopy, a workspace company with a location in San Francisco, and a private equity firm called Symphony Technology Group. Since then, it has announced other tenants including Genesys, a software company, the law firm Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP, and the venture capital firm Menlo Ventures.

The push for more commercial development is not without risk at a time when working from home has become the norm for office workers. According to WFH Research, a collaboration that includes Professor Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University, even the increasingly popular "hybrid" model of work, in which employees come to the office a few days per week, looks nothing like companies' pre-pandemic workplace norms.

WFH Research has been regularly surveying workers on their plans to return to the office, and the April survey, which was released last month, showed the number of work-at-home days at 2.3 per week — still almost half of the time.

In San Francisco, the trend has jolted the downtown area, where office attendance was at just 26.4% in late May, according to a June 12 story in the San Francisco Chronicle, which cited an analysis from Kastle Systems, a security company that monitors access card swipes.

Suburbs, however, have been largely spared the pain. Though Santa Cruz Avenue has 11 vacancies according to Menlo Park's

recent downtown economic study, Presidio Bay is bullish on downtown Menlo Park and its new commercial venture. In talking to prospective tenants during the pandemic, the company recognized that a hybrid workplace is the solution that many companies are looking for, Sanandaji told this news organization.

Springline's two three-story commercial buildings feature flexible spaces that various tenants can use for events, meetings and overflow areas. The flexibility made it easier for companies to commit to leases even without having a clear idea of how much space they'll need for their office employees.

"What we underestimated was the resiliency of the suburban markets and the choice that a lot of occupiers have made to optimize for commute and lifestyle as a result of the pandemic," Sanandaji said.

Springline is among the most ambitious new projects in the area covered by Menlo Park's downtown plan, which runs along El Camino from the city's northern boundary to Watkins Avenue and which includes a vibrant stretch of Santa Cruz Avenue between University Drive and the Caltrain corridor. Compared to Redwood City, which swung for the fences with its downtown plan, Menlo Park has taken a relatively moderate approach that emphasizes retention of the city's "village character."

While vitality is a theme, there is little talk in El Camino Real and Downtown Specific Plan of rivaling San Jose and San Francisco and little appetite for approving eight-story buildings. The focus is instead to develop vacant lots, revitalize underutilized parcels, improve pedestrian amenities on Santa Cruz Avenue, provide plaza and park spaces, expand shopping and dining opportunities and improve east-west connectivity.

"The plan area offers ample opportunities and constraints for improvements, particularly as they relate to the community's desires for enhanced pedestrian amenities and public spaces, a revitalized El Camino Real, an active, vibrant downtown and improved pedestrian and bicycle connections," states the plan, which grew out of a series of community meetings in 2009 and which the council approved in 2012.

The downtown plan established a cap of 474,000 square feet of new non-residential development and 680 residential units, and the city is now close to those goals. According to the city's summary of Downtown Specific Plan projects, Menlo Park had approved 411,841 of new non-residential development, 87% of the limit, and 526 residential units as of this month. The city has also seen 518 new residential units, either proposed or approved, within 17 projects in the downtown plan area since the document's adoption, according to the city.

Menlo Park may not have been looking to emulate big cities when it adopted its new downtown plan, but big-city living has found Menlo Park. The roster of tenants at the new Springline development will include Burma Love, Che Fico and Andytown Coffee Roasters, all of which have their flagship locations in San Francisco; Barebottle Brew Co., a brewery with taprooms in San Francisco and Santa Clara; and Robin, a high-end Japanese restaurant in San Francisco whose dishes range from $99 to $199.

Canteen, a wine bar and cafe being launched Greg Kuzia Carmel, owner of the popular downtown restaurant Camper, will also set up shop at Springline. And its most recent tenant is Mirame, a high-end Mexican restaurant that has a location in Beverly Hills.

"What we were able to do was marry the best of both worlds — give more folks in suburban markets the urban experience in the form of amenity and hospitality standpoint," Sanandaji said.

Whether or not the Springline project is consistent with the plans goal to retain Menlo Park's "village character," it solves a problem that has been befuddling leaders for the past 17 years: what to do with the empty lot in a prime location that has been vacant since its former occupant, a Cadillac dealership, departed in 2005. This lot, and other vacant parcels around the town, have long been seen as an impediment to the vitality of the local economy and a contributor to the city's derisive moniker, Menlo Dark.

"One thing I consistently heard when I first got involved in government was that people were just so embarrassed by those lots," said Mueller, who reviewed the downtown plan as a member of the Transportation Commission before he joined the council in 2012. "We had these open car lots that were just an embarrassment to people when they'd come and visit. They think you live in a beautiful place, but there's these lots that look like just condemned empty buildings in the middle of the city."

Prior efforts to develop in the area have encountered intense community pushback. In 2006, a group of residents rallied to oppose an approved development with 135 condominiums and 22,525 commercial space at a 3.5-acre site adjacent to 1300 El Camino Real, which critics said would bring too much traffic and overwhelm the school system. (An advertisement from the group fighting the development characterized it as "Manhattanization of Menlo Park.")

The referendum petition opposing what was known as the Derry project prompted the council to return to negotiations with the developer, O'Brien Group. The project ultimately fizzled.

The acrimony over the Derry project and general opposition from residents to "spot zoning" for downtown parcels pushed the city to launch the downtown plan. With the city caught in a recession, a key goal at the time was to ensure that the economics worked out for both the downtown area and for the city at large, Mueller said. This meant attracting new hotels and Class 1A office buildings that would provide the tax and other revenues necessary to pay for the costs to local schools of new housing, which would bring new students.

Mueller said he believes the Springline project checks all these boxes. And unlike the prior proposals for the site, it went through the approval process with little pushback.

"It's big, but it is just a beautiful project," Mueller said. "It has all the restaurants and amenities that people wanted. It has big open spaces; it has a dog park. ... It's a project that people in town are going to be proud of."

The downtown plan, he said, was absolutely crucial to the success of Springline and other recent projects. These include Middle Plaza, a mixed-use development with 215 apartments, 142,800 square feet of office space and 10,000 square feet of retail, and the Park James Hotel, which opened in 2018 at 1400 El Camino.

"The one thing I learned on the council in 10 years is that, if you want to get the best project possible, you have to provide certainty to the market as to what is possible so that they know how much they can put toward the investment in the property and how much they need to provide in investment in community amenities," he said.

Success or concession?

Not everyone sees the plan as a success story. Steve Schmidt was one of thousands of residents and eight former mayors who in 2014 supported a ballot measure that would have restricted growth in the downtown plan area to 240,820 square feet of commercial development and 680 residential units. More significantly, it would have barred the City Council from making any modifications to development standards without voter approval.

The proposal, known as Measure M, ultimately lost at the ballot box, with 60% of the voters opposing it.

Schmidt saw the downtown and El Camino plan as far too aggressive when it came to commercial development and too restrictive when it came to allowing the city to demand community benefits. The "predictability" that everyone talks about is something that benefits developers and not residents, he said.

"The city gave up its ability to control the development, and it just turned into kind of a free-for-all or a land rush for the developers to do what served them. ... We were the victims of a marketing campaign by the developers to give them what they wanted without really saying we gave them what they wanted," Schmidt said. "We gave them predictability, but we kind of lost our ability to represent the residents of the city."

While Schmidt doesn't oppose the idea of having a downtown specific plan, he believes the one that Menlo Park has adopted is not living up to the vision that many residents had during the planning process, when many favored a European model of residences above retail. Instead, the city has allowed an influx of office buildings.

And while the workshops focused on downtown to a great extent, he added, the biggest changes are unfolding along El Camino Real and, in most cases, feature large commerical components. Meanwhile, beloved establishments like Pet Place downtown and The Oasis Beer Garden on El Camino Real have closed down in recent years, further heightening local concerns about the rapid pace of change.

"I think the process was well-intentioned, but it was hijacked by the developers and their attorneys and their boosters in the business community," Schmidt said. "It's the way things go. You have to be vigilant and careful about what you're getting."

In some cases, the downtown plan has been used to scale down projects and expand the menu of public benefits developers are required to provide. Stanford University, for example, had to make numerous adjustments before it could win approval for Middle Plaza, including the addition of community amenities such as contributions toward a bike underpass and toward local schools.

Mueller said the changes were prompted by the council's determination that the initial proposal was not in keeping with the downtown plan's Environmental Impact Report. In that sense, he said, the downtown plan worked as intended.

Henry Riggs, a member of the Planning Commission who worked on the downtown plan, noted that it took a "painfully long" time to come up with the vision and finalize the specific plan. The endeavor, he said, "forced us all to be balanced and considerate in our conclusions."

While Schmidt said the new projects were the results of a "marketing campaign" by office developers, Riggs suggested that the city has been lucky to see the types of projects that came forward after the plan was adopted.

"In my opinion, when you're riding an economic boom and a developer comes forward who's willing to put nearly all their parking underground and create public plazas up top, you should celebrate," Riggs said. "Because in lesser economic times, that just doesn't pencil out."

Downtown Menlo Park isn't the only place the city's got plans for residential growth. Just beyond the boundary of the specific plan, SRI has proposed redevelopment that includes 400 residential units along with 1.1 million square feet of commercial space that would replace existing buildings. And the city's most ambitious plan remains ConnectMenlo, which targets the town's eastern industrial and commercial area, near the Belle Haven neighborhood. Approved in 2017, the plan accommodates up to 2.3 million square feet of non-residential space, 400 hotel rooms and 4,500 new residences.

That said, downtown will likely play an increasing role in Menlo Park's housing vision. On June 6, as the City Council discussed potential housing sites that would be included in its Housing Element, members generally supported revisions to the El Camino Real/Downtown Specific Plan that would, among other things, eliminate the plan's cap on new housing and establish a minimum density of 20 units per acre.

Mayor Betsy Nash said she supports the new requirement and the general trend to promote more housing and less office space downtown.

"I think downtown, next to resources, transit and all, is an excellent place to put more housing," Nash said.

Mountain View: Downtown as a civic center

When Mountain View adopted its Downtown Precise Plan in 1988, it was thinking less about growth and more about pedestrians. The plan envisioned downtown as "a place to get out of the car, a place people will want instinctively to walk, rather than drive through."

"It is an active and attractive pedestrian environment, defined by special paving, street furniture and landscaping," the plan states. "Major civic and cultural facilities are located there to contribute to the vitality of the area."

Much like Redwood City, Mountain View has seen a surge of growth in the past year. Most of this growth, however, has taken place away from the downtown. The city has about 30 precise plans covering neighborhoods and commercial areas throughout the city. Its most ambitious recent planning efforts include the 2017 precise plan for North Bayshore, which envisions up to 9,850 housing units and 3.6 million square feet of office space, and the 2019 plan for East Whisman, which envisions up to 5,000 new housing units and as much as 1.2 million net new square feet of office and research-and-development space.

Both plans also envision a host of community amenities: retail, open space and bike and pedestrian improvements. Aarti Shrivastava, Mountain View's assistant city manager and community development director, said many of the city's precise plans also spell out the implementation of the needed infrastructure improvements in the area.

"We're not just building housing and offices, we're actually building resources for the public," Shrivastava said.

It was the same impulse to transform commercial areas with few public amenities into vibrant and attractive neighborhoods that propelled Mountain View to create its downtown plan more than three decades ago, when the planning tool was still new. Shrivastava recalled seeing photos of what Castro Street looked like before the plan was implemented: four car lanes, an abundance of chain link fences and overhead wires, and virtually no trees or sidewalks.

While much of the Midpeninsula area remained decidedly car-centric, former Mountain View City Manager Bruce Liedstrand led the effort to re-envision Castro Street as a pedestrian promenade and a dining destination. That vision has remained steady even as the plan has been modified over the years. The last significant change was in 2004, when the City Council updated development regulations in three downtown areas and revised parking and density standards.

"What it has produced is a set of development standards and guidelines that helped keep development consistent and predictable, so we know that if there was a development proposal, it must comply with our development standards. And the outcome ideally should be wholly consistent with the precise plan," Mayor Lucas Ramirez said of the downtown plan. "In this case, a precise plan really emphasizes pedestrian safety and accessibility."

Precise plans and specific plans are powerful because they allow cities to customize development standards to the unique characteristics of the neighborhoods they cover, he said.

"It's much more challenging to do with conventional zoning," Ramirez said. "I'd attribute this approach to forward-thinking leaders from decades ago who recognized that conventional zoning is a good thing, but if you have to change zoning citywide, when you make the adjustments, it impacts the city in different ways depending on where it's used. It's a more complex modification."

The process of creating a plan also makes it easier for the city to get buy-in from residents when new developments are proposed, particularly ones that would bring significant growth. Ramirez said precise plans allow the city to solicit and incorporate community input far more effectively than it could do with conventional zoning districts. Shrivastava noted that plans allow residents who may otherwise be confused or frustrated by a particular development application to see how it fits in with the city's broader vision.

"The precise plan gives you the method behind what we're seeing. You see more community support because you've been part of the process," Shrivastava said.

The downtown plan in Mountain View is a living document, and city staff is now in the midst of another potentially significant revision, which is being conducted in two phases. The first phase, which is scheduled to be completed later this year, includes strengthening rules around historical preservation, refining design standards for new developments and prohibiting new administrative offices such as tech headquarters at the ground-floor level for a segment of Castro Street.

The second phase, which will be more ambitious, will take a more holistic look at the downtown area and consider broader land-use changes, including strategies to promote more housing. The council will determine the exact scope of the revision next year, when it goes through its strategic work plan for the next two-year period, Shrivastava said.

Ramirez noted that there's been a fair amount of "office fatigue" in the community in recent years, and the second phase will likely address that. These concerns emerged most recently in April, as the council deliberated on The Sobrato Organization's proposal for a 102,000-square-foot office development at 590 Castro St. The council was scheduled to consider approving the project but pulled it off the agenda after getting public pushback over the influx of office growth.

"We hear a lot of concerns about maybe there's too much office or not enough residential, and how are we looking at parking?" Shrivastava said.

Palo Alto: At the crossroads

Redwood City, Menlo Park and Mountain View may be reaping the benefits of specific plans, but Palo Alto's poor track record in this area has been nothing short of puzzling.

Unlike Mountain View with its 30 specific plans, Palo Alto in the past two decades launched just three "concept area plans" — a local variation that considers new zoning standards and land uses for a particular neighborhood.

Neither the plan for California Avenue nor the one around East Meadow Circle/Fabian Way in south Palo Alto was ultimately approved despite years of community hearings and commissions reviews. With little political consensus and growing criticism from growth-wary residents and council members about densification, the efforts were quietly scuttled.

Palo Alto's current effort to develop a new vision for a 60-acre portion of the Ventura neighborhood has done slightly better, with the council voting earlier this year to adopt a new vision. Even here, however, success remains highly uncertain. The process has been hobbled by disagreement between community members and planning staff as well as by a dispute between the city and the area's biggest property owner, The Sobrato Organization, over the area's most critical site: the commercial complex at 340 Portage Ave. that was formerly occupied by Fry's Electronics. Once again, the amount of commercial growth was the key area of dispute.

City staff and their consultants concluded over the course of the planning process that the most economically feasible option on the table is one that includes 126,000 square feet of new office space and 1,490 housing units. Some new office development would need to be permitted as an incentive to builders to construct affordable housing, absent a significant investment of public funds, the city's analysis found.

That, however, did not sway the council, which has opposed commercial office growth. In January, it approved an alternative that would actually reduce office space in the Ventura area from the current 744,000 square feet to 466,000 square feet, while boosting the number of housing units from 142 today to 670.

Palo Alto's struggles to plan for specific areas have not gone unnoticed. Last year, the Santa Clara County Civil Grand Jury released a report that highlighted the city's failure to produce affordable housing and compared its planning policies, unfavorably, with those of Mountain View.

One of the report's key observations was about the different approaches that the two cities take toward specific plans. To match their outcomes for affordable housing with their policy goals, the report stated, "Palo Alto leaders need to employ best planning practices such as creating specific planned areas with identified densities, setbacks, height limits, etc., that support AH (affordable-housing) development.

"Palo Alto should take the time to define specific area development plans with the attendant neighborhood involvement, similar to the Precise Plan process in Mountain View," the Grand Jury report stated.

The council did not take kindly to this advice. The city's formal response to the Grand Jury argued that Palo Alto's struggles with affordable housing have more to do with economics than with planning.

"We believe the primary challenges to affordable housing are economic, and the same economics apply equally in both the presence and absence of specific plans," the response states.

The pushback notwithstanding, the Palo Alto council in late April took a small step to follow the leads of its neighbors to the north and south. It voted 4-3 to accept an $800,000 grant from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) to create what the city is calling a "Downtown Housing Plan." Though it will function much like a specific plan, it won't be as broad or ambitious as those of neighboring jurisdictions. It will identify a vision for housing in the downtown area and create guidelines and development standards that builders would be able to rely on to win expedited approval for their projects.

There are, however, some key limitations. For one thing, reflecting the council's general disdain toward commercial growth, the plan will focus exclusively on housing. And it will conspicuously exclude one of the city's most strategically crucial sites: the downtown transit station at 27 University Ave. This despite a general recognition that the site, which includes the Downtown Transit Center, represents a tremendous opportunity to add a significant amount of housing in the city's most transit-friendly area.

Planning Director Jonathan Lait told this news organization before the April vote that the city worked with the MTC to narrow the parameters of the downtown plan to match staff's limited budget and staff capacity. He noted that the city is already looking at new strategies and standards for parklets and streetscape improvements in the downtown area. By limiting the plan to the 76-acre area between Alma and Cowper Streets and between Lytton and Hamilton Avenues and by excluding the transit center, the city will be able to move more quickly and nimbly on adopting the vision document within three years, as required by the MTC.

"We'll definitely do environmental analysis that would anticipate what development can occur in the plan," Lait said. "Might there be some projects that are different in some ways from the plan and may need additional (environmental) analysis? Yes."

Even with these limitations, some council members see the planning effort as key to meeting their goals in both enhancing downtown and meeting the city's housing goals.

"To me this plan will be one of the cornerstones of our new downtown," Council member Alison Cormack said. "And our downtown is going to have to change based on the pandemic. It's going to have to be different than it's been."

Mayor Pat Burt in April argued that the downtown plan will allow the city to "potentially adjust us from greater office growth to greater housing growth." The key to the success of the new planning effort, he suggested, will be to get buy-in from residents.

"We have a lot of folks who tend to bemoan the so-called Palo Alto Process, and the result is that rather than embrace the values of active grassroots democracy and community participation and people who have an understanding of the context of the community, we instead just hear refrains about how counterproductive our process is because of community participation," Burt said.

"I don't really believe that. I believe the opposite — that it brings real value but that value has to be channeled in a deliberate way," he said. "We can't just assume that we will throw these things together and they will work. We have to have a really good process design to get both valuable outcomes and efficient processes."

Burt was heavily involved in the only instance in recent history in which Palo Alto actually advanced and implemented a new vision for a specific area: the South of Forest Area (SOFA) Coordinated Area Plan, launched in 1997. Prompted by the departure of Palo Alto Medical Foundation from downtown to a new campus on El Camino, the planning effort was completed in 2003. The two-phase plan culminated in the creation of Heritage Park, the city's acquisition of the historic Roth Building, and new retail and housing developments.

Drafting plans that work

Those who have successfully implemented downtown specific plans agree that the key to making them work is a lot of effort upfront. Redwood City council member Jeff Gee cited the years of community meetings and litigation that his city had to go through before its plan came to fruition.

"Change management is very difficult in everything we do. That is always tough, luring people along. We collectively need to find a way to bring people along with the change that has happened over time. And 20 years is a long time to do something."

Consultant Aaron Aknin acknowledged that residents have to be involved early in the process.

"If the community is not onboard on Day One when the plan is adopted, for sure they won't be on in Year Three," he said.

One challenge inherent in planning on such a large and long-term scale is predicting the future needs and concerns of the planning area. Aknin said that it's important for cities that adopt specific area plans to make sure that the CEQA review of this plan covers potential improvements that may later be implemented in the planning area — whether it's bike lanes or widened sidewalks. That way future decisions on individual housing developments or infrastructure improvements won't trigger a full environmental review that would cause delays.

Palo Alto's downtown plan probably won't be anything like Redwood City's. While Redwood City Mayor Hale boasted at the May 25 grand opening of Arroyo Green about her city exceeding the state's mandate for housing, Palo Alto mayors and council members have consistently opposed these mandates, characterizing them as an assault on local control. They routinely lambaste recent laws like SB 9 (which allows lot splits for greater housing density in single-family neighborhoods), SB 330 (which prevents cities from adopting new development standards that delay approval of residential projects) and SB 35 (which creates a streamlined approval process for housing projects in cities that fail to meet their RHNA targets).

But Aknin suggested that specific plans are a way that cities can control their own destinies at a time when state laws are chipping away at their powers to turn down residential developments.

"In general, cities recognize as part of the RHNA process that they'll have to zone for a significant amount of new housing. You no longer have discretion from the planning commission nor the architectural review process. Your only discretion is laying out visions for the plan. The state allows you to do that," Aknin said.

Palo Alto is still months away from launching its process. After the council voted 4-3 in April to accept the MTC grant, city staff put out a request for proposals for a consultant but received no responses. (Lait said some consultants said they did not have enough time to respond.)

On May 24, the effort received a small boost when the council's Finance Committee voted 2-1 to approve $150,000 to supplement the grant. The three committee members — Chair Tom DuBois, Vice Mayor Lydia Kou and Council member Eric Filseth — had all voted against the downtown plan in April, arguing that it would distract the city from its other housing-related efforts, including adoption of the new Housing Element. But DuBois and Filseth changed their minds and agreed to the budget proposal, making it all but certain that the full council will approve it next week when it adopts the budget.

City Manager Ed Shikada suggested at the May hearing that while the plan will take a lot of work, the time is right to pursue it.

"As much as it scares us all with respect to the work ahead involved in delivering this project, I have to say that the confluence of this, along with increase of funding that seems to be going into transportation now, does make this the time that if we're going take this on, it's the time for us to take it on," he said.

Comments