It was just before New Year's when I learned that someone my toddler Theo and I had spent time with had been exposed to COVID-19. We'd spent time indoors together, sharing a meal and watching a Spider-Man movie.

Rapid tests were short supply, but I had some. So I met my mom in front of a COVID-19 testing site, where I had an appointment for a PCR test, to give her two home test kits. The person we'd eaten with tested positive.

It was possible that Theo, a participant in Pfizer's pediatric COVID-19 vaccine trial, was already inoculated against the virus. Or he might have gotten a placebo shot -- participants wouldn't find out until enough data had been collected to "unblind" the study.

Two years into the pandemic, around 19.6 million children in the U.S. are still too young to be eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine. There was no way for us to know if Theo was one of them.

At this point in December, with the omicron variant rapidly spreading, it seemed like everyone was getting a COVID-19 exposure notice, so I felt relatively calm. My husband and I anticipated a potential holiday surge, and had stocked up on at-home rapid tests and gotten our booster shots.

We walked through the possible scenarios if Theo and I tested positive. We agreed that with Theo's general level of exuberance, even while sick, my husband would isolate in the house with us and risk getting exposed; I would need the help if Theo and I both got sick.

We waited five days for our PCR tests, took rapid tests in the meantime and followed up with more PCRs, all negative. Not one of the five other people at the dinner tested positive or became sick. All of us but Theo were boosted. My sister was convinced this meant Theo had received the vaccine, but we still had a month to go before we would know if her hunch was correct.

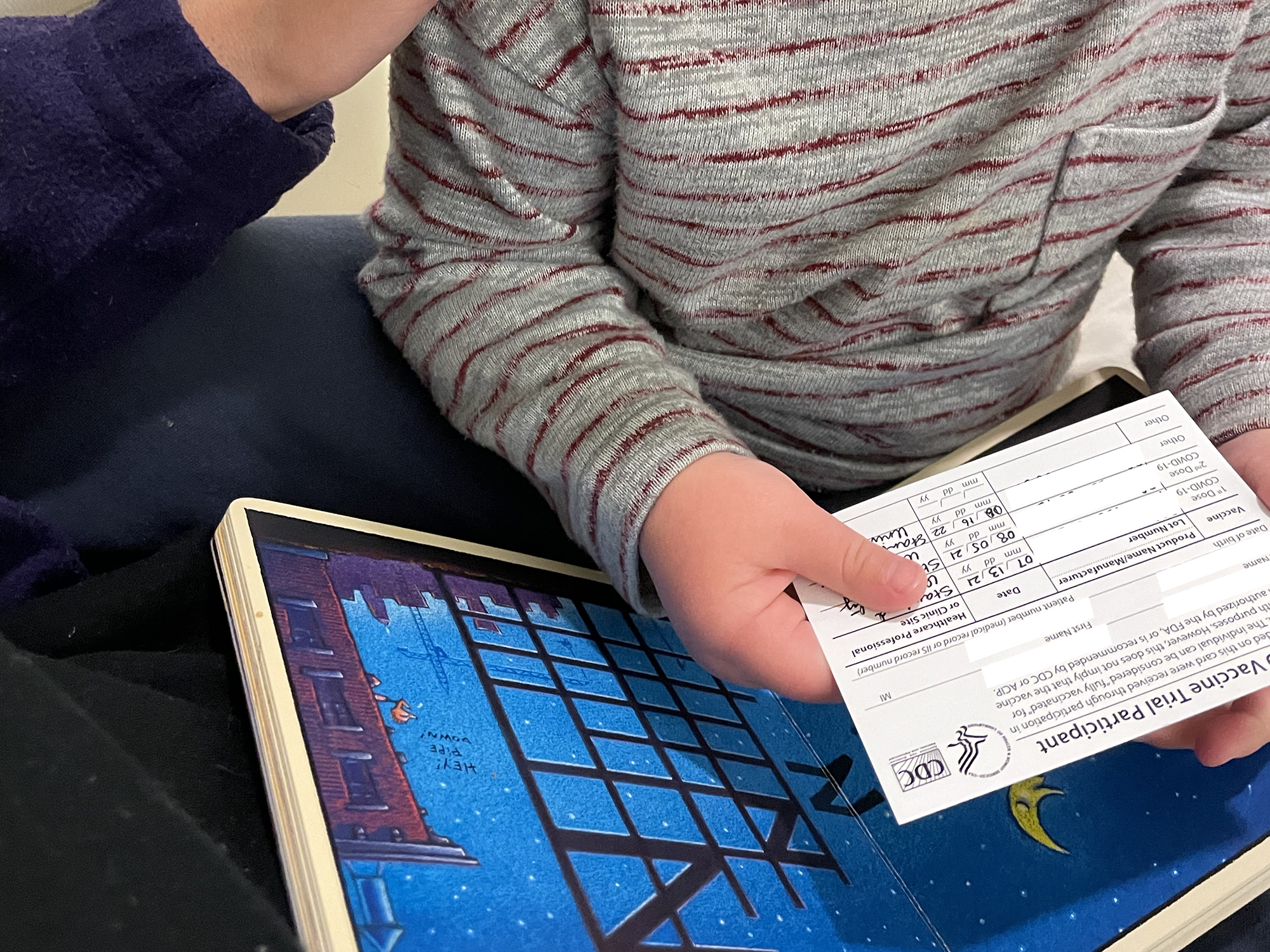

I had documented for this news organization how Theo received his first shot in mid-July in Stanford University School of Medicine's COVID-19 vaccine trial for Pfizer, and another one three weeks later, when he was about 14 months old.

Over the holidays it felt like a race against time. Theo's unblinding wasn't set until late January. And even if he had been vaccinated over the summer, his immunity would be waning.

The unblinding

With the contagiousness of the omicron variant, the vaccine trial's investigators decided to cut out unnecessary in-person visits and said they'd tell us over the phone if Theo had gotten the vaccine.

Since he seemed not to have any side effects from the shots (aside from a very slight fever the night of his second jab), I was surprised to learn on Jan. 27 that he in fact received active doses, not the placebo.

They offered participants who decided to continue participating in the study a third dose as a booster to protect against omicron.

Pfizer also had another reason for offering a third shot. In mid-December the company revealed that, compared to the vaccine's high efficacy in 16- to 25-year-olds, it wasn't proving as effective for 2- to 5-year-olds in its study. (The 3-microgram dose does appear to be effective for Theo's age group, ages 6 to 24 months.) It would evaluate a third dose of 3 micrograms for children between 6 months and 5 years old.

"These updates were informed by the effectiveness data for three doses of the vaccine for people 16 years and older, and the early laboratory data observed with delta and other variants of concern, including omicron, which suggest that people vaccinated with three doses of a COVID-19 vaccine may have a higher degree of protection," Pfizer said in a press release.

On Feb. 16, Theo got his booster. This time, he certainly was more aware that he was about to a receive a shot than he was in the summer, and more squirmy as a result. This time, we knew exactly what he was getting because we had already signed a contract stipulating that they'd unblind the study after six months.

After his third shot, again he had seemingly no side effects. We came back a month after the booster for a blood draw from his arm to check for antibodies, and are scheduled to come back again for another blood draw.

A long waiting game for parents of young children

The FDA approved Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds in late October 2021, which meant kids in that age group could be vaccinated in time for Thanksgiving.

Things weren't looking as rosy for families with children under 5, but health officials were still hopeful shots could be in their arms (or thighs, for babies) by February. In mid-February, the FDA was set to review the Pfizer vaccine trial, but announced a week beforehand that it would postpone its review and wait until data on a third dose of the drug becomes available in early April. This was crushing news to many parents of toddlers.

"It is frustrating that we have nearly reached an endemic phase of this virus and don't have a vaccine for our littlest ones, but it is essential that time be taken to ensure the vaccine is safe and effective," said research nurse Jamie Saxena, one of the investigators in the Stanford pediatric study.

A glimmer of hope came last week, when Moderna announced it will submit a request to the FDA "in the coming weeks" for authorization for a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine series for children under 6.

But the efficacy of Moderna's vaccine was about 40% in children under 6, compared to over 90% in the adult study.

There have been other bumps in the road. Last summer, Pfizer put the study on hold while clinics rewrote the consent form with a warning that myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, and pericarditis, an inflammation of the lining outside the heart, have occurred with some younger people who've received mRNA vaccines. Both Pfizer and Moderna's vaccines use a copy of an mRNA molecule to produce an immune response.

But clinicians now agree that the known risks of COVID-19 and its potentially severe complications, such as long-term health problems, hospitalization and even death, far outweigh the potential risks of having a rare adverse reaction to vaccination, including these two heart conditions, according to the CDC.

Hope for the spring?

Aside from the news from Moderna, Saxena said she hopes the Pfizer vaccine will be approved for under 5-year-olds by the end of April.

Overall, the study participants are doing well, Saxena said.

"I'm looking forward to having COVID-19 vaccines for all ages!" said Dr. Bonnie Maldonado, the lead researcher in the Pfizer study at Stanford, in an email. "Messaging about the safety and importance of these vaccines for children needs to continue."

I feel like my family has been privileged to have a different experience than most families with babies and toddlers, given Theo's vaccination status.

I can bring him to visit his great-grandparents with less fear that he might give them the virus.

We felt comfortable attending his friend's outdoor birthday party. Theo went to Trader Joe's for the first time ever and was a wonderful assistant, taking items from us and placing them in the cart.

He still gets sick, as a terrible bout of norovirus recently reminded us, but we are comforted that he's less likely to get COVID-19 and spread it to others, and if he does get it, is less likely to get deathly ill.

We've dodged COVID-19 thus far, and as he approaches his second birthday in May, we're hoping to be able to throw him an outdoor birthday party if the latest variant doesn't cause a surge in cases the way delta and omicron did.

That doesn't mean we should go back to exactly how things were before the novel coronavirus spread across the world.

If there's anything I have taken away from my experiences these last two years, it's that we need to take care of each other. If you don't feel well, stay home. A negative COVID-19 test still doesn't mean that anyone wants your coughing, runny-nosed self coming to the potluck or to work, especially if you're around infants or immunocompromised folks.

Comments

Registered user

Cuesta Park

on Apr 11, 2022 at 2:45 pm

Registered user

on Apr 11, 2022 at 2:45 pm

"Protected" how? The under-5 crowd had no COVID deaths in the Pfizer trial's control group. The vaccine (treatment) actually had a higher incidence of severe fever as a result of reacting to the vaccine. This is a case of the cure being worse than the disease. Healthy children can naturally fight the virus without any medical interventions. Let them do that.