For Yoshiki Oshima, the memories remain fresh 80 years later.

There was the FBI taking away his father, a farmer who was involved in the local church and the Japanese community. There was the forced evacuation of his family to the Tule Lake camp, one of 10 concentration camps that the United States constructed in 1942 to incarcerate Japanese residents. There was the reunion with his father a year later in Crystal City, Texas, a more secure camp that was run by the Department of Justice and was generally reserved for people that the government deemed to be more threatening.

The Texas camp offered, somewhat paradoxically, more freedom as well as tighter security. Within the camp, residents had more independence. Instead of the common bathrooms and mess halls, families were placed into duplexes or triplexes. Rather than being forced to eat mutton or hash, they were given tokens that they could spend to buy food at the camp market and cook their own meals. Any sense of freedom, however, was fleeting. Crystal City, which was a camp operated by the Department of Justice, had tighter security than most camps, which were run by the Department of the Interior. Oshima recalls the 10-foot-high barbed-wire fences, the guard tower and the mounted police who patrolled the camp.

"Every day, they took headcounts of all occupants in the camp," Oshima said.

Oshima, 94, was 15 years old when his family was forced to relocate from his hometown of Isleton in Sacramento County in 1942. They lost everything, he said, and ended up moving back to Japan once the war ended.

The move was particularly hard on his father. "He didn't have any other place to go," Oshima said. "And my mother was not doing too well and she wanted to go back to Japan because she considers herself a burden to her family."

Despite the losses his family suffered, Oshima felt no bitterness towards the American government. In Japan, he served for the United States occupational force before enrolling in the U.S. Army, serving in the Korean War, going to University of California at Berkeley through the GI bill and getting a job in Hewlett Packard, from where he retired in 1990.

The Mountain View resident was one of dozens of former camp internees who gathered at the Palo Alto Buddhist Temple on Sunday afternoon to recall their experience in places like the Topaz camp in Utah; Minidoka, Idaho; and Rohwer, Arkansas — places that most residents don't know about. Now in their 80s and 90s, they were children between 1942 and 1946, when the camps were in effect. Some remembered their parents' pain at being uprooted from their homes, others recalled their happier childhood moments.

Yoko Kawamura, who was 6 years old when her family was brought from Stockton to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, recalled running through the forest, carving whistles and roller-skating on the smooth floor of the communal laundry room. She also recalls the cramped conditions, with her family of eight confined to two rooms separated by a hanging sheet, the centralized bathrooms and the wire fences and the guard towers.

Kawamura's father served as the block manager, where he planned social activities such as dances for other camp members to keep the morale higher. Once out of the camp, he opened a gas station to support the family.

"They made the best of the situation," Kawamura said.

Menlo Park native Frank Sasagawa, who spent some of high school years in Topaz, similarly recalled his family's struggles, which contrasted with his relatively normal high school experience at the camp.

"What our parents had to go through was completely different. They were removed from their homes, they lost their jobs and put into camps and pretty much lost their livelihood. If was a big question for them, not knowing what the United States was going to do with them," Sasagawa said.

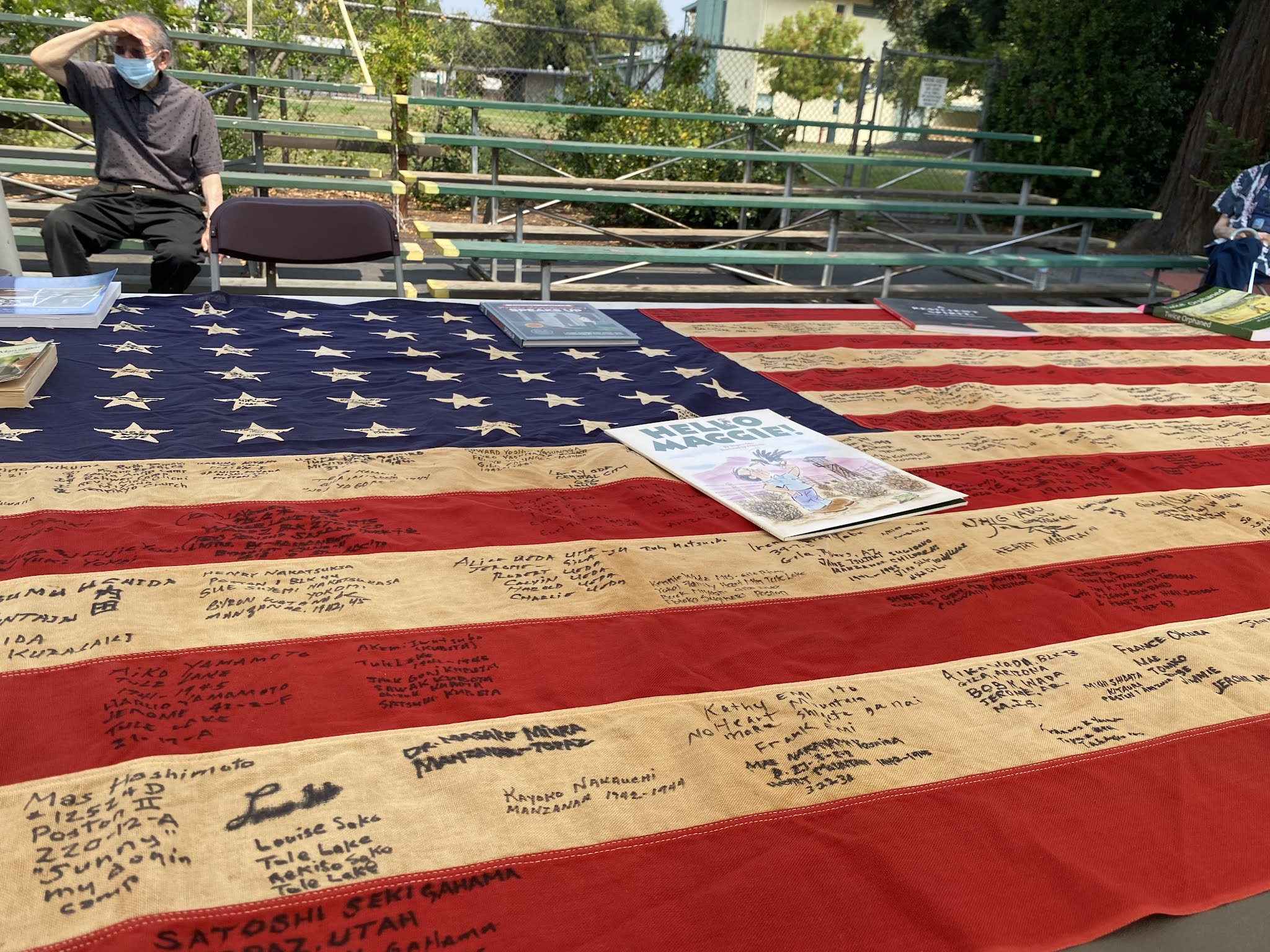

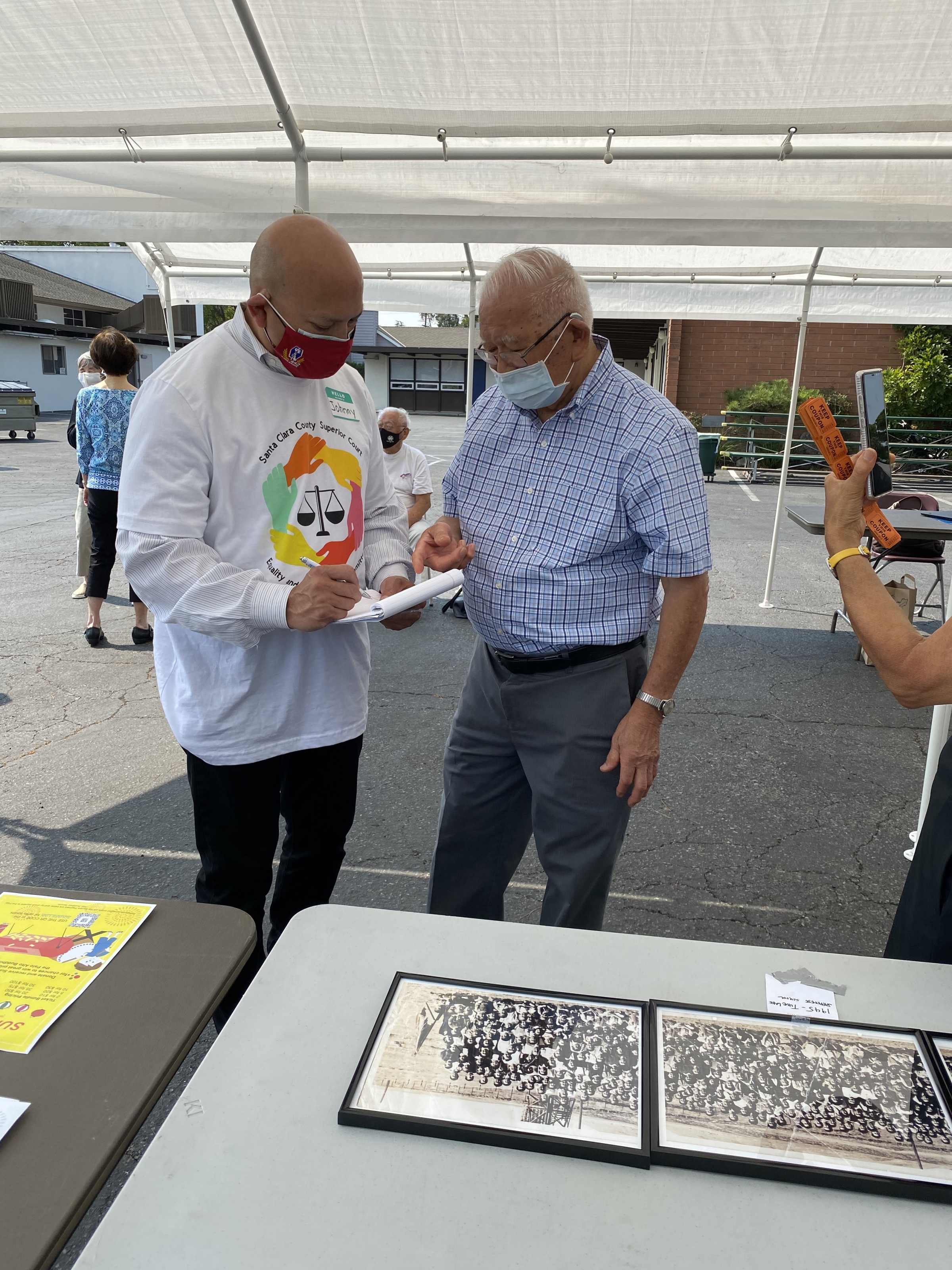

The Sunday event was the brainchild of Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Johnny Cepeda Gogo, who has been traveling around the country and inviting former camp internees to sign one of two U.S. flags. He began the project in March, when former Rep. Mike Honda became the first person to sign a flag (he was interned at the Amache camp in Colorado). Since then, more than 500 people have signed the flag, including the actor George Takei (who was interned at the Rohwer and Tule Lake camps), and the more than 60 people who registered for the Sunday event in Palo Alto.

The number of signatures will increase in the coming months, as Gogo takes his two 48-star flags to Minidoka, Idaho, San Diego, San Jose and San Francisco as part of a tour that includes visits to the locations of every former internment camp. He plans to donate the flags on Jan. 30, also known as Fred Korematsu Day, which is named after the civil rights leader who defied the internment order and sparked a Supreme Court battle. One of his two flags will go to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose. He is working with the National Japanese American Museum in Los Angeles on the second flag. And with the number of signatures exceeding his expectations, he is already planning to go to eBay to buy a third flag, and possibly a fourth.

Gogo said he became interested in raising awareness of the internment camps several years ago after he met Fred Korematsu's daughter, Karen Korematsu, while doing community outreach to promote Fred Korematsu Day. In 2019 and 2020, he began to think of new ways to both raise awareness and to honor survivors of what he calls "prison camps."

"There was barbed wire and guard towers and armed soldiers keeping them on the perimeter. It's a custodial prison," Gogo said. "They had their lives ripped away from them — their businesses, their schools, their livelihood, their social lives — ripped away without due process of law. They were in prison from 1942 to 1946 and the Issei — the older generation — had it the hardest because of the stress of having to try to still provide for their families and try to keep their teenagers' lives as normal as possible to the extent that they could."

In addition to honoring those who went through the camps, Gogo wants the experience to serve as a lesson about not taking constitutional rights for granted. The U.S. has come close several times to repeating its mistakes from the 1940s in recent decades, most recently when former President Donald Trump considered a "Muslim ban" — a policy that relied on the same type of racist hysteria and failure of leadership that contributed to the establishment of the camps nearly 80 years ago.

"What I hope people learn is that we as American citizens have to be vigilant in protecting our constitutional rights because as we've seen during World War II, the government made a decision to bypass the Constitution and mass incarcerate over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals in the United States, primarily on the West Coast, without the due process of law," Gogo said.

Some former camp inmates never recovered their losses. Taz Kuwano, a Palo Alto resident, was 6 years old when the FBI took her father and placed him in a Sacramento jail. The rest of the family was relocated to the Turlock Assembly Center, a temporary facility where her mother passed away. The siblings were then reunited with their father and taken to the Gila River camp in Arizona.

Others were able to resume their lives — or build new ones — after the camps were decommissioned. Pauline Ogasawara, who was sent to Tule Lake and to Minidoka, Idaho, met her future husband at the Minidoka camp. A native of Salem, Oregon, who now lives in Palo Alto, Ogasawara recalled the dances and the social scene at the camps, as well as her jobs as a waitress in Tule and an assistant in an OB ward at Minidoka. After spending some time in Idaho and Portland, she moved to Palo Alto in 1962.

For Ogasawara, who was 16 when her family was incarcerated, biggest complaint about the camp experience was the food.

"I didn't like the mutton. You can smell it all over as you were going to high school," Ogasawara said.

Kuwano, who was 6 years old when her family was moved to Gile River, said she was encouraged by the Sunday event, which allowed more residents to learn about the experiences of Japanese internees. Many people, she said, have little knowledge about the internment camps.

"In high school, I had a history teacher who talked about it and there were so many kids who never heard of it. They all turned around and stared at me and I felt like slumping under the chair," Kuwano said.

She recalled how resourceful her father was upon leaving camp. At a time when food was being rationed, he acquired pigeons and geese to sustain the family. Later he acquired chickens and worked at a nursery, where he grew vegetables. At the same time, he rarely discussed his experiences in the internment camp.

Kuwano said she was gratified by Gogo's project and by the large number of people who showed up to sign the flag.

"I think the younger generation is more proactive when it comes to justice," Kuwano said. "We were pretty passive. Maybe because our parents didn't talk about it much."

Comments