We've been through a lot this past year. Our collective life-and-death battle against a threat we can't see has challenged us in ways previously unimaginable.

But the tide seems to have turned in this war none of us wanted to fight, and talk of vaccines has replaced our nonstop worrying about the effects of the pandemic.

But we're different people now.

During the past 12 months, we've had to defend ourselves and each other using unconventional weapons: awkward conversations with loved ones about what is and isn't safe, carefully arranged but vaguely furtive gatherings, strategic runs to the grocery store and stripped-down living.

We lost track of time but found there were things we valued more than the busy pace of our pre-COVID-19 lives: family, health, friendships, the great outdoors, resilience.

We used to have no problem filling our schedules with activities — always going, going, going — and yet under a seemingly endless stay-at-home order, we sometimes had to urge ourselves to keep on going. This, too, shall pass.

One year in, we asked our readers to tell us about their experiences during this time of living 6 feet apart. They responded with personal tales of what they've learned, felt, been challenged by and continue to face. It's been a mixed bag of boredom, loneliness, anxiety and hardships, but also gratitude, charity toward strangers, opportunity, deepened relationships and determined hope.

We also asked them for their takeaways from this unprecedented, and hopefully not-to-be-repeated, year. Readers who responded include mental health professionals, educators, parents and retirees from along the Midpeninsula. Here are some of their stories.

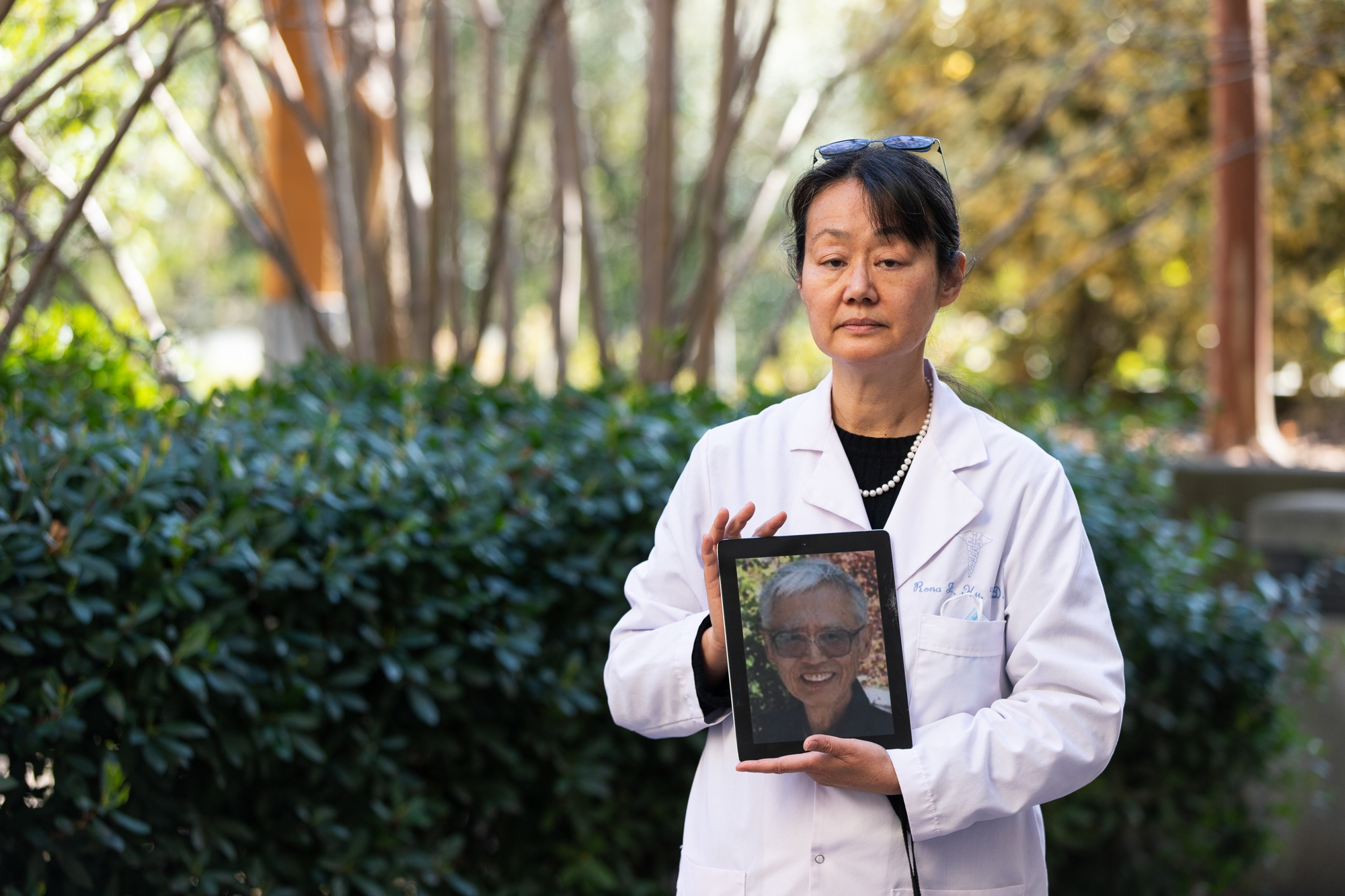

'My 90-year-old father got COVID-19. Against the odds, he survived.'

I'm a psychiatrist, an associate dean at Stanford University School of Medicine, and on the front lines in the hospital. I'm an Asian woman who experienced discrimination and then became temporarily disabled in the middle of the pandemic. I'm a mother, wife and daughter to elderly parents in two different nursing homes.

But the worst — and best — experience of this pandemic was when my 90-year-old father got COVID-19. Against the odds, he survived.

I'd encouraged my parents to move to this area so I could help out, and when my father had a stroke, a neighbor called me, and I rushed him to the hospital in time to save his life. Right before lockdown, my mother could no longer handle his needs and transferred him to a higher acuity facility where he didn't know anyone. Before the pandemic, I'd had dinner with them every weekend, and in between, my husband and I would help with shopping and errands and grocery visits. Now we couldn't see them, and they couldn't see each other, so my dad's mental status deteriorated quickly. English is his second language, but at the new place no one speaks Chinese, so he was confused and frightened.

Working on the front lines and trying desperately to keep from getting COVID-19 or giving it to my family, I was managing as best as possible in the pandemic until August. Then the rain and lightning storm that sparked those awful wildfires caused a dog-walking accident in which I fell down slippery stairs and broke three vertebrae in five places (and a rib).

I was still recovering when, in December, my father developed COVID-19. His doctor at Stanford got him on the list for the monoclonal antibodies that had just been granted an emergency use authorization. His nursing home wouldn't transport him to the hospital for treatment, however, so my husband and I donned yellow gowns, gloves, masks and face shields and transported him ourselves.

He was coughing in our faces with every breath and fighting us because he thought he was dying. (He had a surprisingly strong grip for a 90-year-old, as a nurse and I pried his hands off my husband's neck.) For a few days he was barely responsive and we thought he might die, but on Christmas Day the nursing home FaceTimed us and he was awake, eating and drinking and recognized us and the Christmas carols we sang to him. It was the best Christmas gift ever.

I could talk about being underappreciated as a health care worker and about being furious when people won't wear masks or socially distance. I could talk about 12- to 16-hour days in the hospital, and then hearing people doubt the reality of the illness. I could talk about being mistaken for a patient when I'm not in my white coat, and I could talk for a long time about people fearing me because I'm Asian.

And sometimes I do talk about it, and sometimes I can't. Sometimes the only thing that gets me through tough times is realizing it will make a good story later. So thank you for the opportunity to share our stories.

— Rona J. Hu, MD, Palo Alto

'We are building a bridge to the other side of this.'

Which subject do you think is the hardest to teach online? All of them? That is correct, but in my opinion it is music, specifically choir.

Last March, just a week before schools in Mountain View shut down, I jumped on a Zoom call with choral colleagues from across California. We were all experiencing extreme anxiety because we knew that if school went online, our classes would be impossible to teach. So, we began sharing ideas. This is one thing I love about the choral community: They give freely! We tried out singing on Zoom (it didn't and still doesn't work due to latency). We tested out online platforms like FlipGrid and SoundTrap and Noteflight, and generally plan-icked (Plan-icked = planning while panicking. It's a real thing. Every teacher has done it!).

So, when we started teaching on Zoom the following week, we were ... not ready, but we at least had some idea of what to do. And we helped our colleagues in other subject areas catch up by sharing our resources. I am now known at my school for being "good at tech," which was not a title I ever expected to earn.

Choir on Zoom is like this: I am singing. I hope my students are singing with me. They can hear me, but I cannot hear them. I have them frequently record themselves singing in a program called SoundTrap so that I can give them feedback. It takes approximately 30x as long as it used to for me to give them feedback on their singing, but it's OK because it is something. Most of my students are now comfortable with recording themselves. Some still are not. It's an imperfect process, but we make it work!

To boost morale and to make it seem like we are singing "together," I take these recordings and edit them together in Logic Pro. I also sometimes edit videos of them singing in Final Cut Pro. These are two programs I never wanted to learn how to use, but here we are. The process of creating a virtual choir takes hours and hours. And hours. But it is worth every hour to hear the sound of the choir singing together in harmony.

Here is what I tell the choir: I miss you. I miss singing with you. I can't wait to hear your recording! Your voice matters and I hope you will add your recording to the virtual choir! Thank you for participating and creating something that we can be proud of. Keep singing, if it makes you happy!

Here is what I tell myself (and my colleagues): This is not forever. It is not the new normal. We are building a bridge to the other side of this. Yes, distance teaching is hard and we sucked at it at first, but we got better! Hybrid teaching is even harder, and we will suck at it, at first, but we will get better, just like we did before.

Here is what I will say to you, my community: Keep wearing your masks. Keep doing your part to bring the COVID-19 numbers down. When this is all over, sign your kids up for a choir (or any music class) because we will all need the incredible healing that music provides.

I can't wait till we can sing together, again.

— Jenni Gaderlund, choir director at Graham Middle School, Mountain View

'Given these cracks in society ... there is lots of work to be done.'

Certainly everyone is affected in unique ways by the pandemic, the consequent economic restrictions, the school closures, business failures, remote working and, of course, the infections, hospitalizations and deaths. One obvious takeaway: Life is precious.

Our household currently numbers four persons: two retirees and two adult daughters who relinquished independent apartments and returned home. We appear to have avoided COVID so far. Fairly rigorous adherence to the public health guidelines have become routine. With 100% home cooking, we have a grocery store loop that takes advantage of senior hours and lets us stock up on fresh fruits and vegetables, Safeway items, Costco supplies and Trader Joe's specialities. Home Depot has been the supplier of choice for DIY home repairs, and Lowe's provided us with a pair of propane patio heaters for infrequent chances to invite people into our backyard bubble — 6 feet apart. We do lots of gardening and yard work. We drive our cars almost not at all — so little in fact that the local car dealer keeps trying to repurchase our youngest old car, and the other car in the garage gets driven 20 minutes a week to charge its battery. A Palo Alto 2021 version of Walden Pond?

When the pandemic hit, our youngest daughter was halfway through her master's degree program when on-campus instruction ceased. She returned home to complete her degree remotely, began to apply for jobs, interview, and now is studying for the C.P.A. exam. Our older daughter also gave up her apartment and is job hunting from the spare bedroom.

The "parental units" came to a screeching halt on any notion of Golden Year bucket list adventures. E-books have replaced physical books borrowed from the library. Scissors and clippers bought off Amazon have replaced barber or salon visits.

Gym patronage is gone. Outdoor exercising has largely given way to home workouts, facilitated by a timely acquisition of a spin bike. Flab built up early in the pandemic from stress eating and inactivity has melted away from daily two-hour stationary bike rides ... an excellent way to fill the schedule, catch up on Netflix or even news or financial reporting. Bridge Base Online is humbling. Daily puzzle solving from the San Jose Mercury is a brain teasing ritual.

Daily life, pending the goal of herd immunity, has a distinct Groundhog Day feel. 2020 sucked and 2021 continues the waiting game before it may become safe to fully re-engage with friends and the community and re-start the work/life/leisure balancing act. It feels like mask wearing and increased social distancing will be semi-permanent. The lost years aren't actually replaceable ... the lost present value is a permanent deduction. We now know friends, former colleagues and family members who have gotten infected and some who died from COVID-19. Survivor guilt? We now know shops, businesses and restaurants that have closed and will never re-open. Whereas this was predictable, it is hugely painful for the proprietors, employees, clientele and communities. The post-pandemic customer-serving community will be more barren, increasingly online, and slow to regain critical mass if ever. Fewer cars on the road, remote working and other changes have cut traffic congestion and made parking a snap. Air is cleaner. But suburban and more remote housing has surged in demand as people flee urban densities, risks and office hours. Affordable housing: no.

Huge thanks to the tireless and brilliant efforts of our health care workers and scientists. Equally important have been the essential workers — who risked their lives when they showed up for work — keeping grocery stores and supply chains operating. Unbelievable that the pandemic has played out in a climate of political partisanship, made even worse by the Big Lie that the 2020 election results were fraudulent and the elections were illegitimate. Nothing like a global health and economic crisis to expose the ugly cracks in society regarding racial injustice, income inequality, white nationalist extremism, bigotry, disinformation, and extreme weather conditions brought on by climate change.

Kara Swisher recently mentioned the need in our society for deprogramming. Beyond the pandemic and economic collapse, one takeaway reflects the need for collective reexamination of our legacy. Given the cracks in society — not just in aging infrastructure but in values, habits, bias and the way we treat each other and live our lives — there is lots of work to be done, and it would be a tragic cop-out to assume any chance of going back to the way it was.

— Mark Michael, Palo Alto

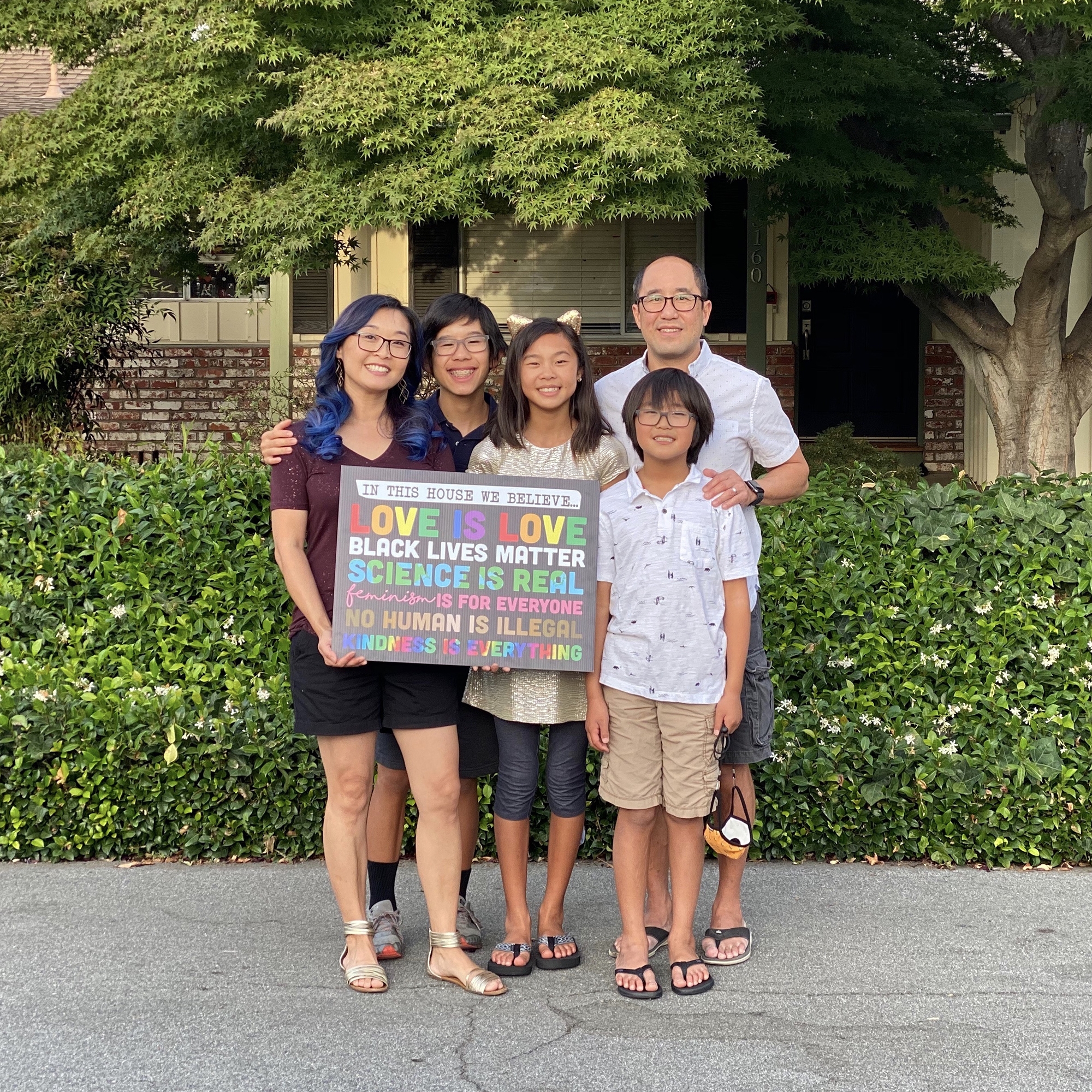

When the going gets tough, create 'Happiness Bubbles'

Here's the story about how we started a neighborhood singalong that we affectionately call "Sun Mor Singers" and a public Facebook page called "Happiness Bubbles" where we share videos of our singalongs, our gratitude for health care and essential workers, and just positivity with others.

Our family of five (plus two dogs) lives on Sun Mor Avenue in Mountain View. A few days after the official shelter-in-place order on March 16, 2020, we discovered a Facebook group called "Quarantine Singalong" that was started by Ilana Minkoff in San Francisco. We joined that group on March 21, and every night at 7 p.m. we would stand outside to applaud the health care workers and sing a song. We invited our neighbors to join, and the three neighbors adjacent to us would come outside almost daily to join us. We continued to do that every night, posted a video of our song, and started to spend a few minutes chatting with our neighbors (standing across the street from each other) after each singalong, which turned into the best part of our day. We did this for 70 nights straight until May 29. (The last official night of Quarantine Singalong ended with an epic version of Bohemian Rhapsody).

But after that larger group stopped, we didn't want to stop connecting with our neighbors, so we decided to continue on ourselves and meet outside three nights a week. And that led to starting our own Facebook group called "Happiness Bubbles" so we could post those videos of our neighborhood singalongs. (My kids came up with the idea for the name because happiness can bubble up to the top and make you feel better, and bubbles can also make you happy — see our page here.)

We have been singing with our neighbors since then and haven't stopped yet! We are now on our 180th neighborhood singalong this week. It has definitely been a silver lining for us during this past year of the pandemic. It has helped to have something fun and positive to look forward to (sometimes we have costumes or themes), and it has helped us reconnect with our neighbors and get to know them better. We even started sharing grocery runs and other things as a result of the relationships we have developed. This has been an emotional blessing since we don't have any family members who live close by. And it has helped us remember to have a moment of gratitude each day, even on the days that we don't feel very positive. I have also made new friends from the original Quarantine Singalong, and we keep in touch over Facebook.

We often have neighbors drive or walk by while we are doing our singalongs, and they have also commented that seeing our family singing or dancing in the street has brightened their day. It has really helped us to try and spread positivity during this difficult year.

— Hera Hong Lee, Mountain View

Diagnosed with leukemia four months before the pandemic

At the age of 5, my daughter Hadley, now 7, was diagnosed with leukemia, four months before the pandemic closed everything down. We went from the gut-wrenching experience of learning how to navigate childhood cancer while feeling wrapped in love with an amazing amount of support, to feeling shunned by our community when the shelter-in-place order started. Suddenly nobody wanted to be near us, when what we need most is our connections with our friends.

This past year has been the most painful time in our lives, not because of fearing the virus but because of how all the restrictions have negatively impacted our family. Losing all in-person support during a time when we are still reeling with a traumatic diagnosis has only made a terrible situation even worse. Hadley only got to attend a few months of kindergarten before being hospitalized, and she was just starting to get ready to return to the classroom when school went virtual. Distance learning doesn't work for her, so we've struggled this past year and will be pulling her out of the district to officially home-school instead, where she'll have more flexibility.

I worry that by next fall schools won't be back to normal, and I'm not comfortable sending her anywhere that I'm not allowed to be on campus, which is what I fear will be the case. She has to wear a mask more than most people and has been doing so since she was diagnosed in November 2019, and we have no desire to put her in school where she'd need to wear a mask all day.

Navigating the world of childhood cancer and how it affects our whole family while also dealing with a pandemic is truly a horrible experience. Still, despite the hardships of this year, there have been some wonderful moments thanks to those who continue to try supporting us in whatever way is possible. Friends have bought us groceries, lent us a car to take Hadley to her chemo appointments, sent thoughtful gifts to both of our children, and when her hair started growing back and she asked to trim the sides, someone donated a professional haircut to her! I also encourage our friends to donate blood in Hadley's honor, since she's needed many blood transfusions. You can see more of her story at tinyurl.com/hadleysstory.

I was warned that friendships have a tendency to fade away when your child is diagnosed with cancer, and I doubted that would happen since we had so much support and everyone seemed like they wanted to help us through such a trying time. Unfortunately the pandemic caused everyone to experience their own trying times, and it's harder to find the helpers when everybody is struggling.

The collective grief we are all feeling after a year of hardship is magnified for me, and carrying that weight feels impossible at times without being able to share the burden, but how can I ask those I love for help when they need help as well? It's just a lose-lose situation, and each day I hope we are one day closer to a return to normal.

— Katy Crain, Mountain View

'I will never take a hug for granted again.'

Hugs are everything.

We hugged our family, friends and co-workers. Did we ever think of a time when we could or would not hug? Not only was it unimaginable, we never thought of the hug and all its significance. A hug shows love, it shows sympathy, it shows respect and most of all it feels good.

Hugs are one of the things that can feel good for all parties. We have hugs for two or hugs for a group. We have big bear hugs, strong breath-take-away hugs and gentle, kind hugs.

Would we have ever imagined not having any kind of hug or not giving any hugs?

A year into the COVID-19 pandemic and our shelter-in-place requirements mean lots of things are not fun. We have lost jobs and sources of income. We are in jeopardy of losing our homes, too.

Nothing could compare to losing a family member or friend to this horrid disease. It's a miracle that in one year a vaccine can mitigate this virus and help us all look forward to a more normal lifestyle.

I feel so grateful that my family is safe and so far I have survived all of this. My grandchildren and I have invented pretend hugs when we see each other outside, masked up and socially distanced. It is something but really not enough.

I know I, for one, will never take a hug for granted again.

— Geraldine MacDonald, Los Altos

Creating space outside of work

I am exhausted. I work all of the time. There is no meaningful division between my work life and my home life, and I haven't had a vacation day in over a year.

I am eager to get back into my office — my real workspace — and to be able to travel again so that I can more easily create non-work times and spaces in my life.

— Eric Goldman, Mountain View

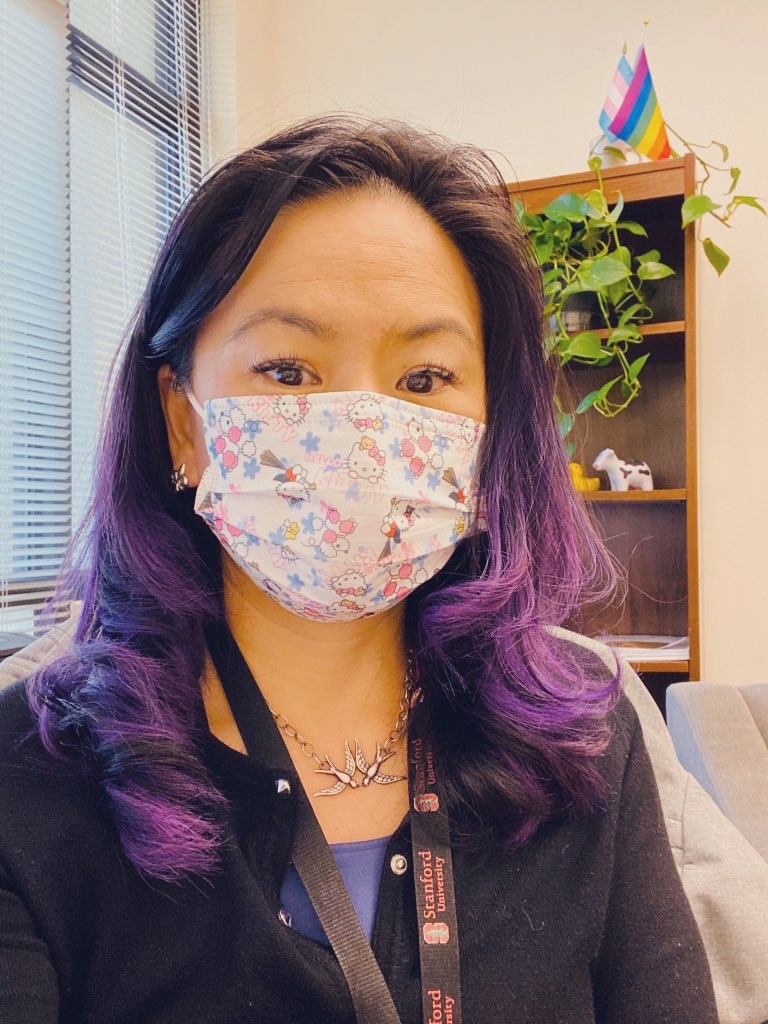

' I don't know how we are going to properly grieve.'

I am a clinical psychologist at Stanford.

I am grateful that under shelter in place I am no longer rising at 5:30 a.m. daily and spending eight-plus hours of my life every week trapped in the gridlock on the Dumbarton Bridge to get to work on campus.

But...

I miss my mom, whom I pushed into early retirement to Taiwan last March — bidding her goodbye at empty SFO without even daring to hug her. She has been safe, happy and free in Taiwan while COVID-19 ravaged the USA. So I am glad we made the decision for her to go, but I'm sad that she abruptly left 42 years as a Californian behind like a COVID-19 refugee.

And...

As a clinician who specializes in grief work, I am exhausted beyond articulation and filled with dread about the years ahead. We are living with a scale of loss impossible to comprehend yet. Starting a year ago, I started to meet with therapy clients, students who are mourning the COVID-19 deaths of family members. Young people sobbing, grieving on Zoom memorials, sharing via telehealth therapy and grief-support meetings.

It's a privilege to hold people's stories, beautiful, loving stories of uncles cooking favorite dishes, parents shipping ice-packed home goodies across state lines, aunties who inspired career choices, cousins, friends, mentors — each individual person dead before their time.

It's only been a year. I don't know how we are going to properly grieve all the dear ones we have lost and the impact on entire families and communities.

— Helen Hsu, Fremont

'People are starved for human interaction of any kind, no matter how limited.'

I had thought about trying videoconferencing for most of the three years that Curious Minds, an adult discussion group, had met weekly at the Woodside Village Hub. Meeting in person provided a rich, three-dimensional experience, particularly valuable when topics ranged all over the map, both literally and figuratively; among over 100 others, they have included Russia, Great Britain, Africa, Kashmir, the Middle East, health policy, the solar system, homelessness, intellectual property, happiness, the film industry, humor, geopolitical forecasting, the media, food and, unsurprisingly, elections.

Then the pandemic hit, forcing the experiment. I figured if it didn't work out, we could suspend meetings until the pandemic was over, likely in just a few weeks. Ha!

I assumed the number of participants would decline from the 10-15 we typically had, and the meetings would be shorter. While Zoom provides video of participants who choose to share it (most do), the small video tiles on a flat screen was a big step backward, making it harder to figure out who wanted to speak and when to move the conversation to a higher level or drill down to a lower one. But we adapted to the new medium. On the positive side, it allowed people from multiple time zones to be able to participate. That has also allowed us to more frequently invite people with particular knowledge of a topic, since travel was no longer a factor. It is not uncommon now for discussions to span 10 time zones.

The meetings aren't shorter and typical participation has grown to 15-20, perhaps in part because people are starved for human interaction of any kind, no matter how limited. It's gone well enough we will likely continue videoconferencing for at least some meetings after the pandemic is over.

— Bob Sawyer, Woodside

'I moved back into the home I grew up in. There were enormous adjustments for all of us.'

For my family, this year of relative isolation hasn't been completely unprecedented; I started my hibernation nine months earlier when I moved myself and my son from our home in Oakland to my parents' house in Palo Alto.

It was a necessary move for many reasons, but not an easy one. It involved walking away from teaching, a job I had done with love for almost 25 years. My son left his friends and neighbors and the home he'd grown up in. I moved back into the home I grew up in and tried not to regress to my teenage years. There were enormous adjustments for all of us in terms of privacy, expectations, habits formed over decades. There were crises large and small. And all of this came months before COVID-19.

As I made my introverted way through the first months of my move, I got a job working from home, which was great until California's gig worker bill took effect in January 2020. I tried to navigate the intergenerational challenges of my new situation. "Sandwich generation" sometimes felt more like "rock and a hard place" generation.

When the shutdown first began, my focus had more to do with my son's schooling. On Friday, March 13, it was announced that schools would close "for a few weeks" until after spring break, and then resume. I picked him up, he collected all his belongings, and we went home without what turned out to be a final goodbye to in-person fifth grade.

I suspected the closures were going to last longer than predicted. At first, I had believed the people who opined that the illness would burn out quickly, but it soon became clear that we were in a major crisis and that our country's leadership was not going to take appropriate action. I abandoned hope of stable schooling and tried to keep him entertained and somewhat educated at home. He was extremely anxious about COVID-19 and would barely leave the house.

It took some time for my parents to realize just how curtailed their usually busy lives would have to become, and it was awkward when I had to put my foot down on the side of safety versus their freedom to visit friends or work at their volunteer jobs. Suddenly they seemed so very fragile in their mortality. Suddenly I was the adult telling the teenagers there was a curfew. It was uncomfortable for all of us.

My contract work, which had already been spotty since the gig law, dried up. I threw myself even more into gardening, taking out my frustrations by eradicating the invasive bamboo and rejoicing with each seedling I coaxed from the ground. I started a daily gratitude writing practice. I wrote a speculative "worst case scenario" story about the administration's handling of the disease.

I walked and photographed and walked some more. There was therapy. There were books and books and books. There were short bursts of artistic creation. My son became too anxious to sleep in his room and has been in mine every night for the past year. I set up an outdoor desk and started tutoring my neighbor's kids when it felt safe to do so. I took lots of breaks from it because I would grow terrified that I would somehow make my parents sick. The doomscrolling online became an obsession.

Then came the fires, which left us trapped inside as ash rained down outside. I felt claustrophobic and would wake at night unable to breathe from the stress of being shut indoors. My already-haunting dreams turned darker and woke me in a panic. I burst into tears one morning as my father told me he was driving up to the archery range; his sense of smell had disappeared several years ago and he couldn't smell the smoke that hung heavy in the air. I was certain the hills would spontaneously combust and he would die. My mother held me as I wept out my accumulated months of fear and frustration. Of course he returned unscathed, but I could feel myself unraveling. Everything seemed filtered through a haze of ashes and virus.

And of course there was the political situation, which raised my usually low blood pressure until I had to stop watching the news. I wrote to voters in swing states and donned my mask to join a march in support of Black Lives Matter, but I kept feeling like I wasn't doing enough. The sigh of relief I breathed on Jan. 20 seemed to remove a hundred-pound weight off my shoulders.

My partner, who lives in San Francisco, has saved my sanity in so many ways, by taking me away on hikes and kayaking journeys, by engaging my son in construction projects and Nerf battles, and in the fall, by converting a garden shed into my "sanity shed" — a tiny office in which I sit right now, away from the sturm und drang of the other parts of the sandwich, the tightrope I walk between the rock and the hard place.

My son has begun spending more time outside, and the next crop of vegetables and wildflowers is about to sprout. All in all, my family has been lucky. We still have our health, a yard to run around in, and enough to eat. We share our gratitude each night at dinner and are thankful that we have each other to talk with, to offer support to, to embrace.

My parents just received their first vaccines, which will begin to allay my anxieties about their health. We have survived for this long and learned that we have the skills to do so, despite the emotional toll this year has taken. We mourn those who have not been so fortunate and we make plans for how to rejoin the world and continue to work to make it a safer, kinder place.

— Beth Baugh, Palo Alto

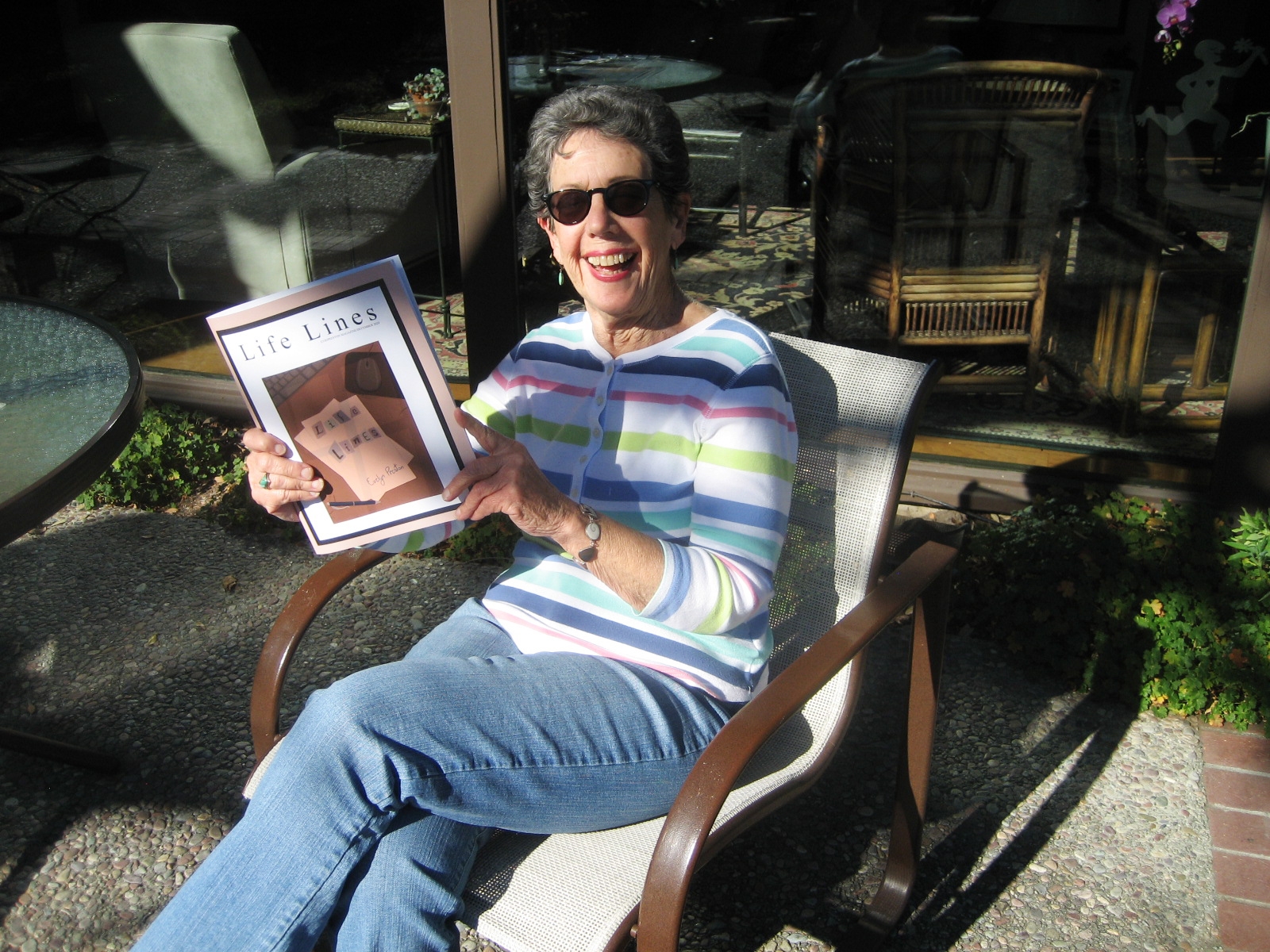

'I count my blessings and thank my lucky stars.'

During the early months of the lockdown, and under "house arrest" by my concerned children, my altered lifestyle offered uncluttered time, the perfect opportunity to "do my own thing" and follow through on my plans to update and revamp 40 years of written snapshots — from Palo Alto politics to the Palo Alto process, from teaching and traffic to obits and compost bins — many that appeared in our hometown paper. However, my solo first attempt, dubbed a passion project by a California Writers Club expert, unexpectedly bloomed into a family affair — a COVID-19 bonus.

"You need other eyes, Mother," said my son, suddenly a tough-as-nails editor. "No one can proofread their own work." Following his lead to "spiff up my copy," my clever daughter-in-law morphed into art and layout director as well as professional publisher. My granddaughter contributed the cover. We all stayed in our own corners, meeting by phone or via computer, and my other children added positive input. Far from any "publish or perish" mindset, becoming an in-house joint venture made all the difference and put a special spin on our self-published, nonprofit, from-the-heart adventure.

Who knew my adult children were ... so grown up, so accomplished? What a joy to re-meet them as competent, efficient pros in an unlikely field. Turned out, I couldn't have done it without them. Starting slowly last March, we got serious over the summer and ramped up to "publish" a sleek, magazine-style compilation well before Christmas.

We'd met our goal to share this legacy laced with laughter — my "Life Lines" — with friends and relatives across the years and the miles. We mailed them off as a holiday surprise, the right time and era for a unique greeting — and the perfect time to reach out and touch someone ... on paper. A gift for all of us, the response was better than a Pulitzer.

The perfect venue also helped. While others lamented their COVID-19 confinement, I was on a long vacation, with literally all the comforts of home. I could enjoy the amenities of remaining "en vacances," groceries delivered and house maintained, constant calls, caretaking and concern from my kids and connections. I stretched and stooped with the TV exercise lady, which set my morning schedule. Like a smuggler's set-up in the driveway, I handed off hard cash in exchange for a kind friend's farmers market surplus. She and a few others snuck in the backyard for short and distanced visits. My postage stamp property teemed with hidden wildlife, and walking beat driving; I "leaned in" and thrived.

How fortunate I was with everything in place to ensure a "vulnerable" senior's well-being. No shopping, no "must-do's," Zoom meets and greets, lectures, a movie or two and an almost daily, email pen pal. But mainly I was writing — work that I loved.

A few of my essays noted inevitable sadness of irreversible losses that others have experienced deeply. I'm grateful but never smug about how well I survived.

"The good old days" are gone, erased by the devastating detour of 2020. However, at my age, I believe that it's mainly for the best. All things change. We longtime residents are still here to mark the foibles and follies of late-20th century as well as its wonders and woes well into the 21st. I count my blessings and thank my lucky stars. Within a year, I'm vaccinated against a scourge especially aimed at us old folks. It's again time to prove our inner resources, share, give back, think young and, of course, plan ahead...

— Evelyn (Evie) Preston, Palo Alto

A weak army fighting an all-out war

In digging deep this past year into the world of aerosol SARS-CoV-2 transmission (small airborne particles that travel more than 6 feet and linger in the air for hours), I am flabbergasted. The failure of our leaders to understand aerosol transmission is astounding. We're in an all-out war with COVID-19, spending trillions, but we're uneducated, disorganized and divided.

Throughout the U.S., deadly health orders prioritize (extremely rare) surface transmission and fail to mention aerosol transmission.

Pre-COVID, I played goaltimate frisbee at Greer Park with my buddy Frank Vigil. We both had sports and professional interests in COVID-19. We both want to get safely back on the grass at Greer, but goaltimate has enough panting and close contact to be problematic until every player is vaccinated. Frank comes from an Intel cleanroom background and is an investor on the leading edge of indoor air safety. My work serves COVID-19-vulnerable populations.

Frank and I climbed the COVID-19 transmission knowledge ladder together. We were able to access national and local experts (Professors Michael Osterholm, Shelly Miller, Jose-Luis Jimenez and Erin Bromage; ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers); a scrupulous local HVAC professional; four commercial property managers managing over 30 million square feet; public transit safety staff).

I listened to struggling Palo Alto merchants lament arbitrary health orders: "Indoor dining open at 25% makes no sense because ventilation varies. The public health officer said my napkin holder was dangerous."

On Aug. 13, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group had a Zoom meeting with Santa Clara County Public Health Department's Dr. Sarah Rudman. Contradicting current science, she claimed, "We're finding that transmission is from face-to-face contact, not from the virus floating around in the air. So HVAC would be a lower priority item, and we need to focus on high priority items." Rudman's comment led me to advocate to Silicon Valley leadership to prioritize protections against aerosol transmission. But it's tricky to be an effective advocate with limited power and zero scientific credibility. On the other hand, this is an issue where you can invest a few hours with the upside of saving lives.

On Dec. 9, I succeeded in persuading the world's No. 1 transmission expert, Prof. Shelly Miller, to credibly advocate about aerosol transmission to Silicon Valley, and that made the difference. She wrote in an email to Dr. Sara Cody, among others: "The evidence for how the SARS-CoV-2 virus transmits differs from the assumptions in California state and county guidance. Evidence shows that surface transmission is rare whereas aerosol (i.e. small airborne particle) transmission is the only explanation for every superspreading case study." (The letter's available at bit.ly/HealthySCC.)

There are about 20 aerosol scientists with university labs that undertake primary research on live virus particles. Before SARS-CoV-2, virus aerosol transmission was well-understood by these scientists, but the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) deliberately ignored that science. The aerosol scientists have grown increasingly frustrated because they knew how to avoid the holiday spike in cases.

On Feb. 24 at Joint Venture's State of the Valley Conference, Cody stated, "We now know much of COVID-19 transmission is aerosol or airborne, a bit of it is droplets, and very little is on surface." But then she failed to explain the need to update public health orders to increase safety.

Though nine months late, Cody still might have made the first statement of this sort by a U.S. public health staff member or epidemiologist. I'll take 10% credit for her statement.

(Note: These views are my own, not the views of Palo Alto Transportation Management Association.)

— Steve Raney, Palo Alto

'One thing I have definitely learned is that I get by giving.'

I never envisioned I would write every single day for a year. I just set out to have something to do when we got locked down. You know, what are you going to do with the time? And so I set out with this little goal to write something every day, and I took photos of local flora and fauna. Then I got to the point of doing quotations to enhance what I was writing about, and then I shared this with a lot of different people.

I posted this every day on Facebook and I have a distribution list of about 55 people. My goal was to do something inspirational for others, so we could be helping other people get through this. Never envisioned I would write a full year.

Then people from around the country started sending me pictures and quotes to share. So it became a living, breathing project; people feel a little bit ownership.

One thing I have definitely learned is that I get by giving. I receive by giving. And to me the fact that I had to create something interesting every day, I got as much as I gave to others in the process.

I really have had the time to stop and smell the roses — and photograph them. And I've learned: learned about my community, learned about the flora, the fauna; what time of the year they bloom.

One big takeaway is that I found quotes by people and I didn't know who they were, but I found that they were interesting people. I learned something new this year every day.

And I think I learned something about myself: If I stayed positive, I could reach deep inside and find some strength to keep going and try to inspire myself in the process of inspiring others.

See Sharlene Carlson's daily writing project here.

— Sharlene Carlson, Palo Alto

'I went to a store I rarely frequent, just to see people.'

Being retired, I am used to being home during the day, working out with friends at the gym, and generally having lots of freedom. Overall, there are a half-dozen events that most impacted me in 2020:

1. Having my roommate home — good for me, bad for her. Her 9-to-5 job at a swim school was considered non-essential. She also was not able to teach her dance classes at gyms, which were all closed.

2. I found myself getting annoyed with perfect strangers — those who don't mask up. Still a sore spot, even though Dr. Cody said we can unmask when outside but maintain 6 feet of distance.

3. When it comes to mental health, I only had one major meltdown and several minor ones (basically just bad moods). I relied heavily on the park by my home to be outside and signed up for virtual walks, as well as online/Zoom exercise classes to keep me connected. Recently I went to a store I rarely frequent just to see people.

4. Having a major vacation and two trips to see family canceled.

5. Appreciation for Trader Joe's' and Target's senior hours, which control the number of shoppers at any one time. However, at the beginning of the shelter-in-place, I tried to order groceries from Safeway online — the groceries would arrive in 10 days. I quickly got used to ordering more necessities online and using restaurant pick up.

6. The search for vaccines: I have been a patient of PAMF-Sutter Health for more than 30 years. I am so disappointed with Sutter's response to vaccine distribution. When roughly half of the population of Santa Clara County is affiliated with either Kaiser or Sutter, and neither delivers, something is very wrong. (I am aware both facilities get the vaccine from the state, and if there is no vaccine to distribute, that's it.) But Sutter's lack of communication with its patients has put me in a position to look at another private provider for my health care. I thank Supervisor Joe Simitian and the county for opening up its vaccination facilities to everyone.

— Irene Schwartz, Mountain View

'Now I have to rebuild my business from the start.'

In November 2019, I finished a doctorate in health care focusing on seniors and Alzheimer's, rented a Mountain View office, and began a new business providing testing, lifestyle therapies, and support groups for those with concerns about Alzheimer's and other dementias.

In 2020 I faced long lockdowns that prohibited seeing clients and severely limited the kinds of services I could provide. Federal loans helped me pay office rent but little else. Nobody wanted to see doctors out of fear of becoming infected by the coronavirus.

As of now I have to rebuild my business from the start, figure out how to repay federal and student loans, and provide services for the increasing numbers of people with cognitive problems, some of which are now related to COVID-19. But I have fewer financial resources to do this. It's gonna be a bumpy ride.

— Dr. Elna Tymes, Mountain View

'Life feels more like existing ... rather than actually living.'

Learnt to Zoom and other things I would never have seen a reason to learn. I have baked bread, cakes and cooked much more than usual. I have read old books and watched old movies; I stay away from up-to-date ones since seeing people do things I am not allowed to do is depressing.

Have walked miles both around the neighbourhood and in nature. Have worn old clothes most of the time and rarely worn makeup. Cried quite a bit and felt very fed up on many occasions.

Life feels more like existing or survival rather than actually living. Really want to see friends, family, travel to visit my Mum, and see a few happy, smiling faces when I go out. I am so missing smiles and eye contact with people. Can't stand the way people cross the street to avoid you, or not recognizing if someone on the other side of the street is a neighbor or not.

— Carol Rogers, Palo Alto

'This time has made me conscious of the needs of those less fortunate than I.'

Along with many others, I've learned to adapt to new ways of working, worshipping, attending events and meeting with business colleagues, family and friends. With my family members all living far away, we connect via Zoom and so see each other and play new games together.

Living in a cohousing community, I'm blessed with caring, mutually supportive neighbors. We all assiduously mask and remain socially distanced, thereby being able to meet outside, two households at a time. All of us have stayed healthy: that is, no COVID-19 cases.

Normally I travel a couple of times a year to see family and visit other places, but I feel that will come again, as will visits from guests, which I have missed, especially international ones.

This time has also made me conscious of the needs of those less fortunate than I, and I'm trying to find ways to be supportive. I feel content, appreciate all the good that individuals and groups are doing for others, and am thankful.

— Elisabeth Seaman, Mountain View

'Job interviews over Zoom this year felt like blind dates.'

There is much that we took for granted before COVID-19 — for example, working together in an office. Job interviews over Zoom this year felt like blind dates: One by one, I met people with no opportunity to really get a sense of what it might be like to work with them.

When I landed a consulting job this past fall, all of the meetings were on Zoom. I had to jump in with little opportunity to figure out to whom I could or could not say what I was thinking. How could I tell who would understand that being provocative could also be constructive? How could I tell who might be threatened by my suggestions?

In the past, I found my allies outside the meeting room. At one meeting where many but not all decisions were already in place, options ricocheted across the table, and I strongly pushed for what I thought the company should do even if more senior people disagreed with me.

As the statistician and I headed to our offices after the meeting, I shared my strategy: "I don't say anything unless I'm pretty sure I'm right."

A week later at a meeting someone asked the statistician if she agreed with me. She replied, "I always agree with Susan." In addition to being a wonderful compliment, it was an endorsement of my strategy.

Physical proximity may give you the chance to say things that might not be said over Zoom. Before COVID-19, a photograph, a piece of artwork, some article of clothing that might spark a connection or just the intuitive sense that it's OK to say something.

At a job interview once, I was greeted by a man whom I realized I'd met several years earlier. I recalled a photo on the wall of his office at the previous company, along with the memory of my unpleasant connection to that company. As we walked the 50 feet from the sign-in desk to the conference room, I blurted out what had lingered in my mind for years.

"I forgive you for having worked at XYZ," I said.

"I forgive you for having worked at QRS," he immediately replied, referring to one of my previous employers.

Unknown to me at that moment, I had just insulted the CEO of the company that I was hoping to work for. But the next day I was offered the job and so began a wonderful friendship.

For me, the value of casual interactions, at work and outside of work, has become magnified this year. Picking up books curbside at the library is great, but social distancing means few opportunities for conversations. One pre-COVID day at Rinconada Library, a librarian asked me if I liked the Grateful Dead because of my tie-dye T-shirt with dancing bears. That question led to many more interesting discussions over the following years.

I so look forward to resuming those discussions in our vaccinated future.

— Susan Light, Palo Alto

Find comprehensive coverage on the Midpeninsula's response to the new coronavirus by Palo Alto Online, the Mountain View Voice and the Almanac here.

Comments