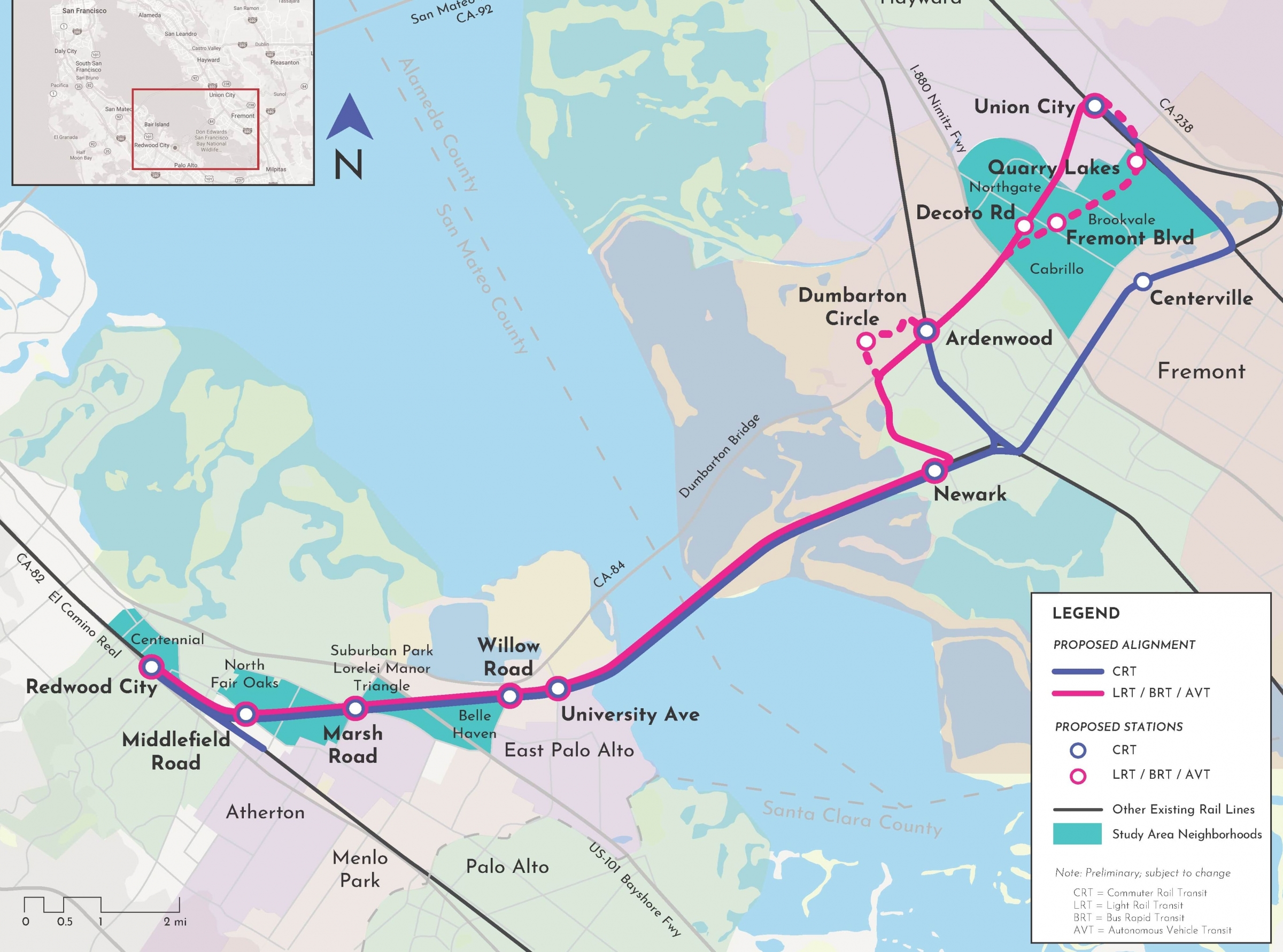

Among residents and transportation professionals on both sides of the San Francisco Bay, interest is picking up in the Dumbarton Rail Corridor project, a potential 18-mile public transit route that would connect Union City to Redwood City, with stops along the way in cities including East Palo Alto and Menlo Park.

Viewed as a "game changer" by some, the new transit system could ease the maddening daily traffic gridlock on the Dumbarton Bridge — and roads leading to and from it — as well as provide residents easier access to Caltrain on the Peninsula and BART in the east bay.

At a virtual meeting on Monday night, project staff and consultants presented the progress made to date on the project, which would use the defunct, century-old Dumbarton rail bridge south of the Dumbarton road bridge as the basis for the cross-bay route. So far, the project team has documented the current infrastructure conditions along the route, forecasted ridership numbers for various proposed stations and developed a range of transit alternatives. It's also estimated costs of the project, which would require a complete rebuild of the Dumbarton rail bridge.

The San Mateo County Transit District — along with partners Facebook and the Plenary Group, a public infrastructure investor and developer — are exploring four possible modes of transportation: commuter rail transit, light rail transit, bus rapid transit and autonomous vehicle transit. All four transportation modes would operate on electricity, not diesel, the consultants said Monday.

Traveling the whole route would take about 30 minutes, they said.

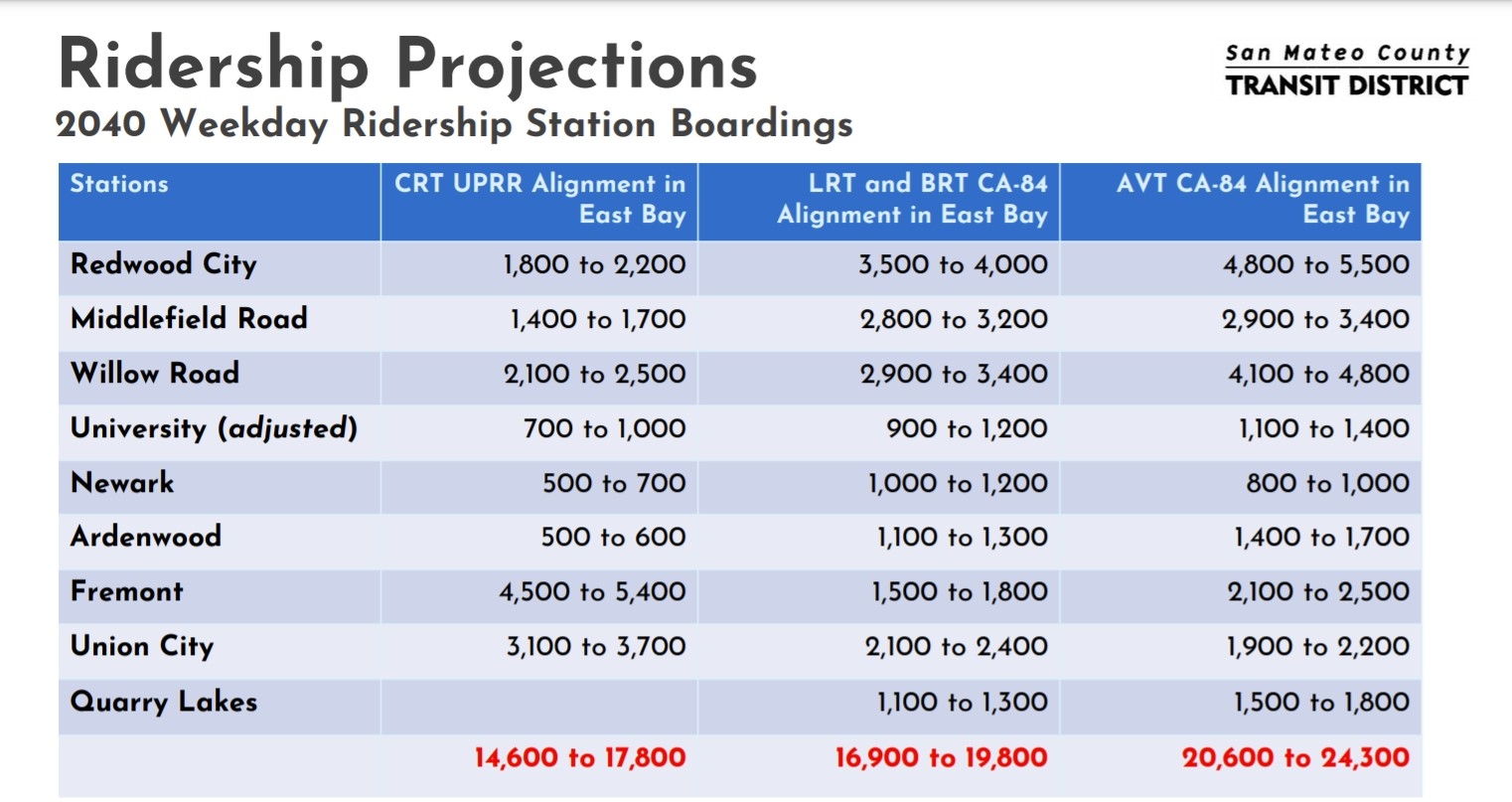

Commuter rail is similar to Caltrain and would cost the most to build: $3.32 billion. It could carry the most passengers at once, however — nearly 600. But trains would come about every 20 minutes, the lowest frequently out of the four transportation alternatives. It would also handle the fewest passengers per day, between 14,600 and 17,800, according to consulting firm HDR Engineering.

Light rail generally requires its own track system with overhead electricity lines. It could cost $3.22 billion, and one train would transport 428 passengers, according to ridership forecasts from HDR Engineering. Light rail trains would arrive every 10 minutes. This mode could transport 16,900 to 19,800 passengers a day.

Bus rapid transit, described as being "rubber-tired light rail" or a cross between traditional buses and light rail, could accommodate 244 passengers per train and would be the least expensive of the four options, costing approximately $2.43 billion. Like light rail, it could carry 16,900 to 19,800 passengers a day, with similar train frequency.

The final transit mode, autonomous vehicle transit, is an emerging technology that uses independently operating pods to transport 22 riders at a time. It has never been scaled up for mass transit use, according to HDR Engineering, but potentially could carry the most passengers of all four options: 20,600 to 24,300 a day. Pods would arrive in intervals of between one-and-a-half and five minutes, the consultant stated. The cost to build an autonomous vehicle system could be similar to that of bus rapid transit, or $2.49 billion.

Regardless of which alternative is ultimately chosen, the project also includes as a component a regional network of bike and pedestrian paths.

The proposed transit system would ease traffic on the Dumbarton but address only a fraction of the congestion: It could serve between 14,600 and 24,300 passengers day, compared to an estimated 70,000 vehicles that used the Dumbarton Bridge daily before the pandemic.

Nonetheless, for local residents like Mark Dinan, the project can't come soon enough. The East Palo Alto resident and civic volunteer has been tracking the project, which got a jump-start in 2018 when Facebook stepped forward to form the Cross Bay Transit Partners and fund necessary state and federal environmental impact analyses, as well as a fiscal impact analysis. Early discussions of the project at first didn't include a transit stop at University Avenue in East Palo Alto, Dinan recalled — a possibility he found unthinkable.

Dinan points to large planned developments, including a set of office towers at 2020 Bay Road, which could bring tens of thousands of new employees to the city.

"These are big, Oracle-sized projects," he said, referring to the Redwood City campus of the software giant.

"If you look at the development planned, there's got to be a public transit solution here," he said, while also noting the lack of regional transit service to the city of roughly 30,000 residents. "East Palo Alto is a city on the move. If half of it gets built, you'll see a lot of office workers."

Dinan said that before the pandemic, rush-hour traffic was already so bad that he wouldn't dare drive his son home from downtown Menlo Park after a late afternoon activity. Instead, they'd stay in the city for dinner, just to wait out the drive home that, under normal conditions, should only take 10 minutes.

"Our traffic is incredibly bad," Dinan said, and without a project like the Dumbarton Rail Corridor, it'll only get worse.

Advocating for a Marsh Road station

Skip Hilton, a Menlo Park resident, is also bullish on the Dumbarton Rail Corridor, but he's also got a concern: Initially, the project included a stop at Marsh Road, but after ridership projections were completed, the project staff dropped the station due to "low performance."

According to a ridership map, a Marsh Road station would attract 400 to 500 riders, while stations at Middlefield Road and at Belle Haven/Willow Road would draw about 3,000 each.

Hilton questions whether the study area around the station, one-third to a mile, was broad enough to truly assess potential ridership. The station, he said, would serve four neighborhoods: North Fair Oaks, Lorelai Manor and Suburban Park in Menlo Park and Friendly Acres in Redwood City.

"I see this as a huge benefit to people in surrounding neighborhoods to access Caltrain and BART," said Hilton, who has been following the project for years, even before Facebook initiated the partnership.

He noted that ridership projection for the University Avenue is actually lower than that of Marsh Road — 300 to 400 riders per day — but consultants said the East Palo Alto station is included because the city is underserved by transit.

"Marsh Road is also underserved by transportation. We should have all the stops," Hilton said. "More stations and access is better."

Consultants at the meeting stated that every additional stop would add five minutes to the route's travel time, but Hilton noted that taking a stop out would also reduce the number of people using the system.

"It doesn't make sense to reduce passenger volume. That's the linchpin" to effective transit, said Hilton, who himself has commuted by Caltrain.

Hilton's requested the ridership studies so he can analyze them. He also said SamTrans would find there is tremendous interest in a Marsh Road station if the agency were to reach out to those four neighborhoods.

While Hilton would like to see a Marsh Road station, Dinan has a preferred mode: Specifically, he hopes to see the commuter rail option chosen — the extension of either Caltrain or BART from the east bay. It makes the most sense, he said, to extend an existing network rather than create a new short-haul system from which riders then would need to transfer to Caltrain or BART.

"What I would say is that it's got to be seamless," Dinan said.

With a Caltrain extension, Dinan envisions biking from his home to the new University Avenue transit station, hopping on Caltrain and whizzing up to San Francisco or heading down to San Jose — without changing to another transit system.

"Coordination" has also been the mantra lately among leaders of local transportation agencies. With 27 separate entities, the Bay Area has been called the "most fragmented public transit network in the country" by advocacy group Seamless Bay Area. Regional planning efforts are underway to try to lower hurdles to taking public transportation, including the study of coordinating schedules among agencies and unifying fare systems so passengers can easily hop from one transit service to another.

The Dumbarton Rail Corridor project has miles to go before it could become a reality, however. While it is included in the Metropolitan Transportation Commission's Plan Bay Area 2050 with a completion date in 2036, for now, the project needs the SamTrans board of directors' approval of preferred alternatives to submit for environmental review. The staff's analysis of the alternatives is scheduled to be presented in May or June, according to Carter Mau, deputy CEO and general manager of SamTrans.

"The board will decide how to proceed forward," Mau said Monday. He added that while the Dumbarton rail bridge is "quite a unique regional asset … there has never been enough support to fund any proposals to reactivate the railway."

Funding remains unknown, although the project team states on its website that the project is eligible for public funding under the recently passed Regional Measure 3 (bridge toll tax) and San Mateo County's Measure W, as well as Federal Transportation Administration Capital Investment Grants and other U.S. Department of Transportation programs.

Dinan said he'd love to see the Dumbarton Rail project receive significant federal aid from the new presidential administration.

"I'm all for it. I'm a huge fan," Dinan said. "For all the taxes we've paid in Silicon Valley, what have we gotten back?"

SamTrans is currently taking comments on the Dumbarton Rail Corridor project. Email comments to dumbartonrail@samtrans.com.

Comments

Registered user

Old Mountain View

on Mar 17, 2021 at 3:03 pm

Registered user

on Mar 17, 2021 at 3:03 pm

Yesterday's Voice comment still holds. 'Viewed as a "game changer" by some,' OK. Yet strikingly little historical reflection occurs, especially in a proposal that could "be a game changer" back to a type of service used a century ago, and abandoned.

"A public-transit route connecting Peninsula to East Bay" exactly characterized the original 1910 Dumbarton Rail Bridge, linking US rail services to the peninsula's north-south line -- now Caltrain -- and thus to SF. Revolutionary ("a game changer") in its time, long before the Bay Bridge or Golden Gate Bridge.

In 1910, San Francisco had been for 60 years the major population center and port on North America's Pacific coast. The rail bridge connected the busy Port of SF with the "mainland" US by rail.

Had you predicted in 1910 that even local rail services (rapidly growing then) would be abandoned in the 1950s for private cars, you'd have been laughed at. Just as if in turn you'd predicted in the 1950s that private car commutes might later revert back to rail travel. The question today becomes, what changes considered clever right now will be laughed at 40 years in the future?

Registered user

Cuesta Park

on Mar 18, 2021 at 8:30 am

Registered user

on Mar 18, 2021 at 8:30 am

Consolidation not Increased "fragmentation". That's how my quant hatted head looks at this (other people's) problem. The posting above is right - envision the advantages of a consolidated past mass transportation system.

BRT can connect to the current HOV and developing HOV lane system. An electrified "CalTrain extension" can connect to the soon-to-exist electrified CalTrain system. The first has wildly adaptable inexpensive "stations" (bus stops) and totally adaptable 'last mile(s)' optional on-street routing. The later - fits in with the 'to-be' CalTrain successful system, but has limited 'last mile(s)' adaptability.

And to pay for it?