Ron Davis believes reforming the police is not enough. It's time to reimagine it.

Davis, who served as East Palo Alto police chief between 2005 and 2013 before becoming executive director of President Barack Obama's President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, observed that the nature of police work, whether it's in Palo Alto or East Palo Alto, hasn't changed in decades. Police departments remain similar, in structure and design, to how they were in the 1940s and 1950s, he said.

But given the historic function of police in a society where systemic racism permeates, this failure to change has created a problem.

"We police in pretty much the same way and we police for the same reasons," Davis said Thursday evening at a virtual town hall sponsored by Embarcadero Media. "But we were designed to enforce Jim Crow laws. We were designed to contain and to oppress communities of color. So until we remove that structural racism, that systemic racism, then everything else we're reforming, we're just putting Band-Aids on the festering wound of racism."

The conversation, titled "Race, Justice and the Color of Law," was moderated by Henrietta Burroughs, executive director of East Palo Alto Center for Community Media.

Sponsored by Embarcadero Media, it brought together police chiefs and community members to discuss the topics of systemic racism, police transparency and ways to overcome obstacles that for decades have stood in the way of change.

The list of ideas included repealing policies that allow officers to purge their records of citizen complaints; discouraging use of force in police training; reforming the appeals process for officers facing misconduct allegations; and bringing in the community to discuss a fundamental question: What role should the police play in the modern society?

The Thursday discussion came at a time when police departments across the nation are rethinking their service models after weeks of demonstrations following Floyd's death. In Palo Alto, about 500 people marched in downtown Palo Alto on June 19 to celebrate Juneteenth, a holiday that commemorates the end of slavery, and to hear speakers recall the racial discrimination they experienced in their hometown. And the City Council has just kicked off a process of reviewing and updating policies in its own police department, which has recently seen two lawsuits alleging excessive force.

On use of force

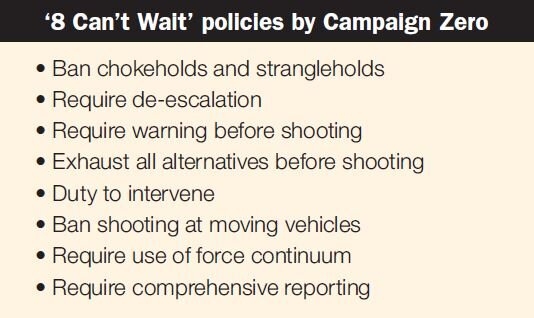

One good place to start, the entire panel agreed, is the 8 Can't Wait platform, which calls for such policies as banning chokeholds, requiring de-escalation, mandating that officers intervene when a colleague is using excessive force and prohibiting shooting at moving vehicles.

Everyone agreed that the measures are reasonable and that most departments already have many of these measures in place, either because of state mandates or local policies. Palo Alto Police Chief Bob Jonsen noted that the department has just adopted a ban on carotid control hold, a policy change that was proposed by officers themselves. The department, he said, continues to actively evaluate its policies for consistency with 8 Can't Wait.

East Palo Alto Police Chief Al Pardini said his department made the same move. Pardini called 8 Can't Wait a great "prompter" for discussing change.

"I looked at those eight different items and ended up immediately meeting with the police unions and taking the carotid restraint out of our use-of-force policy," Pardini said.

But Davis said that while the 8 Can't Wait policies are "a good start," departments need to constantly reinforce in their use-of-force policies sanctity of human life. The more officers value life, the more they'll look for ways to use non-lethal force.

"What shocked the country in watching 8 minutes and 46 seconds was not just the brutality of the moment," Davis said, referring to the May 25 killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. "Do you know how much you have to devalue life to sit there for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, while you're killing somebody? That means that person was dehumanized. That's the part of the structural racism that's there."

On systemic racism

Panelists agreed that police departments are a microcosm of the broader community and, as such, inevitably reflect the systemic racism that has long been embedded in the wider society. Olatunde Sobomehin, CEO of StreetCode Academy, an educational nonprofit in East Palo Alto, said at the town hall that the experiences of Black people are rooted in the racial hierarchy that has existed since the first European settlers came to America, stretching through 200 years of slavery, 50 years of Jim Crow laws and the current system of mass incarceration.

The fruits of this root, Sobomehin said, are the experiences of the 8-year-old child, who feels lonely as the only Black kid in school, or the 15-year-old, who is confused because he doesn't understand how someone can stand on another man for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.

"It's caused me to weep profusely because I'm now facing the idea that my kids will have to one day realize that it's not about what they do, it's about the racist system that they're in," Sobomehin said.

Change, he said, is well overdue.

"Now is our time. It's our Emmett Till moment. It's our 1969 moment. It's a once in a generation moment to uplift the entire system," Sobomehin said.

Paul Bains, president and co-founder of Project WeHope and pastor of Saint Samuel Church of God in Christ, concurred. Bains, who serves as chaplain to police departments in Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and Menlo Park, said racism in America is a system that tears at the fabric of everything from fair housing and a fair justice system to food insecurity.

"Is there racism in the police department? Yes there is, but there's racism in all other areas too, like institutional racism in academia. I feel the police department is one aspect where we have to root out racism, but there's many other areas of society we have to work on as well," Bains said.

On police accountability

While the process of addressing the problem is expected to be long and difficult, Winter Dellenbach, an attorney and community activist who founded Friends of Buena Vista Mobile Home Park, proposed one policy change that she argued would make an immediate difference in the police department: repealing a provision that allows police officers to have citizen complaints expunged from their records, in some cases after as little as two years. Internal investigation records, meanwhile, can be removed from their records after six years.

This, she said, makes it difficult for police departments to ensure that they don't hire officers with histories of misconduct.

"This is wrong, this is serious," Dellenbach said. "If you're trying to make sure you're not doing lateral hires for misconduct, if you're trying to track a record, this is not good practice."

When asked whether he would support a law that would eliminate the policy on purging records, Jonsen said that he is committed to keeping his officers accountable but argued that the system of disciplining an officer is complex. Some of these policies, he noted, are rooted in state laws — including the Peace Officers Bill of Rights — and would be difficult to abolish.

"There has to be a system that's designed, and this is where it gets complex, to where there's a balance and there's a fair due process associated with it," Jonsen said. "

"It's such a complex structure that to disentangle it on a statewide or even national level is going to take some work, it's not going to happen overnight," Jonsen said.

Davis took a clearer position.

"I think the answer should be 'Yes,'" Davis said. "This is one of those structures that, although it had honorable intent, has had a very damaging effect. … You should not use discipline from 10 years ago to keep penalizing someone who made a mistake. They should have the ability to learn from mistakes in their career and keep growing. But the idea that you would destroy a record from someone who has been given such enormous power, the power to take freedom, the power to take life — there is no complexity with that."

Sobomehim also called the policy on purging records wrong, particularly given the fact that 2.3 million people are incarcerated, in many cases for non-violent crimes, and don't have the same luxury.

"To me that's hypocritical, when there is literally a quarter-million children who are locked up for life for a non-homicidal thing they did as a kid," Sobomehin said. "Now we're not allowing for records to be expunged for children, but for police officers, who have the power to take lives, to take futures, (records) are now expunged."

On arbitration

Davis and his colleagues said a major obstacle is the existing police union contracts, which make it hard in many cases for police departments to discipline officers facing misconduct allegations. Pardini concurred and noted that in some cases, the arbitration process makes it easier for officers to challenge and overturn suspension and termination.

"What we see, and where it comes back to haunt police chiefs is when you have a serious case and you try to terminate someone and they go to arbitration," Pardini said. "And maybe they get a suspension, but you don't want this person on your police force based on what they've done and how they conducted themselves, and they get ordered back into police force."

One possible reform, Pardini said, is taking arbitration out of the hands of attorneys and employing retired judges, who are better suited to fairly evaluating the cases.

Davis noted that arbitrators often use a higher standard than chiefs in evaluating misconducts and the chief, in some cases, may lose before the case even starts. An arbitrator may also see a financial benefit in "splitting the baby" and reducing the proposed punishment, a result that may help them maintain their employment as arbitrators. He suggested that arbitrators be required to use the same standards as chiefs in evaluating an officer's misconduct.

Jonsen warned that changes to arbitration practices are something that police unions would be very resistant to, particularly when a new chief comes in and starts implementing significant changes.

"There's concern that a new chief could come in and start disciplining people excessively, with no protection," Jonsen said.

Davis agreed that changing the rules would be tough, but argued that this should be put on the table during contract negotiations.

"It's going to be a heck of a fight, but it's going to be worth it if you can get a good appeal process that's fair to the officer but not an obstruction to the constitution of policing," Davis said.

On the path forward

The police chiefs and the community activists agreed that addressing systemic racism and reforming police work is an urgent task that should involve the entire community. Dellenbach said the society has a "historic window" that won't be open for long and that residents and police leaders have to jump through it to address change and institute police reform.

Sobomehin said the time is now to "reimagine what our community could look like." Davis proposed a "truth and reconciliation process" to examine systemic racism. The truth may hurt, he said, but "selective ignorance is fatal." Bains said that it's going to "take everyone to lean in to resolve those systemic issues."

"Every voice should be at the table and not on the menu," Bains said.

Jonsen also said he is committed to moving ahead with changes in the Palo Alto Police Department to improve transparency and accountability.

"What's really profound right now is the energy among the community and the quickness with which things are happening, not like any time I've ever experienced in my career," Jonsen said. "That's exciting for this profession, because the time is now. If we're going to look to make some major changes in this profession, I think the time is now to do that."

Comments

Another Mountain View Neighborhood

on Jun 26, 2020 at 3:15 pm

on Jun 26, 2020 at 3:15 pm

We need to go a lot further to overall bad police policies. First and foremost we should dispan every city police force and streamline the department's into county police. So there is a police hiarchy in Santa Clara, San Mateo, SF ect.. only. This would save enormous amounts of money for tax payers. It should also apply to Fire depts. Of course, the city council's would all have to agree to fight the unions that would furiously oppose this.

Cuesta Park

on Jun 26, 2020 at 4:02 pm

on Jun 26, 2020 at 4:02 pm

Personally, I think police unions are no longer necessary. I'm a huge labor union supporter but I don't consider police unions to be in the same category.