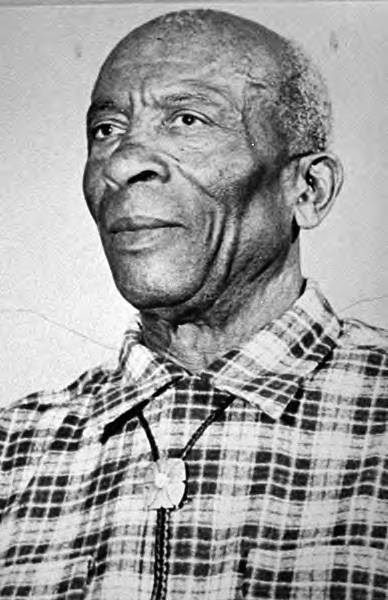

Decades before Ronald McDonald House opened its doors as a residence for families of seriously ill children undergoing treatment at Stanford University Medical Center, there was McDonald Home. Named after Sam McDonald, one of the earliest African-American residents to settle in Mayfield (south Palo Alto), it was founded in 1919 as the Stanford Convalescent Home for Underprivileged Children but renamed in 1959 to honor the countless hours McDonald devoted to the home and its children.

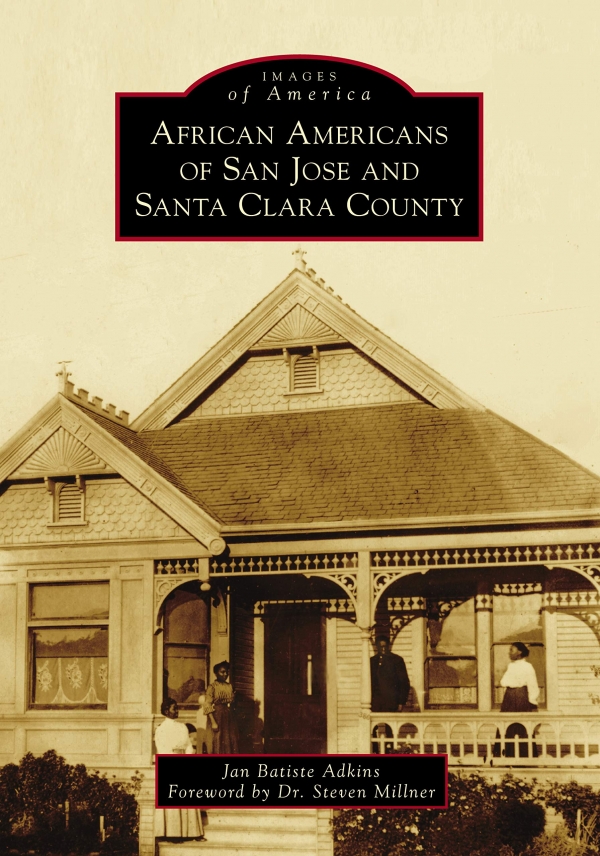

McDonald, the grandson of freed Louisiana slaves and superintendent of buildings and grounds at Stanford's stock farm, is among the dozens of early African-American residents in Santa Clara County featured in author Jan Batiste Adkins' newly released book, "African Americans of San Jose and Santa Clara County." The book traces the history of local people of African heritage and their roles in everything from agriculture and technology to politics and education through 185 photos with accompanying text to tell their stories. The book, released on Jan. 28, is part of the "Images of America" series by Arcadia Publishing.

Adkins, an adjunct faculty member and English composition and literature professor at San Jose City College who has been researching local black history for more than a decade, said she hopes her book will shed light on the area's early African-Americans because many of these stories have never been documented.

"This is history that's not readily available," she told the Weekly in a telephone interview last week. "These are hidden histories."

Adkins said she began researching the stories of early black settlers after her students starting asking about the role African-Americans played in local history.

"I didn't have the answers, and when I went to get information, I couldn't find anything," she said. "I didn't have information about where people lived, what kind of opportunities were available or why they came to the area. That prompted me to do the research myself. I wanted to learn and know more ... and that's how it started."

Palo Alto, she said, attracted settlers for many reasons. The first group of African-Americans began settling there just before the turn of the 20th century to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad or on the Stanford campus for the university and its employees.

The earliest of these residents were porters who lived on Fife Avenue in Mayfield near the Stanford train station, which served as a stop between San Francisco and Monterey, Adkins said.

According to Adkins' book, there were nine African-Americans living in the city in 1900, including "Pop Harris," an escaped slave who opened a shoe repair shop on the Stanford campus with his family in 1892. (His son Fran later opened Fran's Market, which operated on the corner of Lytton Avenue.)

Adkins said after World War II, Palo Alto, as well as San Jose, became attractive for different reasons — technology and industry.

"Employers recruited African-Americans from black colleges from around the country to work here," she said. Roy L. Clay Sr., founder of Rod-L Electronic who became known as the "Black Godfather of Silicon Valley," and technologist Frank S. Greene, who developed high-speed semiconductor computer-memory systems at Fairchild Semiconductor R&D Labs, were among those early tech pioneers to settle in Palo Alto.

Adkins said one of the biggest surprises she didn't expect to find while researching Palo Alto was the story of Eichler Homes.

"I kind of assumed there were restricted convenants there because that was the case throughout the Bay Area. That did not surprise me. But what did surprise me were the Joseph Eichler homes."

The Palo Alto real estate developer did not discriminate. He built homes and established nondiscriminatory policies in the 1950s, she said.

"His feeling was if you had the money and you could afford to buy, he would sell," she said.

That's why in the 1950s and '60s many African-Americans (as well as other ethnic groups) moved from their original communities along Ramona, Homer, Channing, Bryant, Cower and Fulton streets into other neighborhoods once restricted to white residents, she added.

Adkins' quest for information has taken her from San Francisco, down to Monterey and finally to Santa Clara Valley, where she discovered that five mulatto families settled in San Jose in 1777 as part of the original pueblo established during the Spanish era.

She published her first book "African Americans of San Francisco," in 2012, followed by "African Americans of Monterey County" in 2015. Adkins said she decided to publish a third book on black pioneers in Santa Clara County after discovering that many of San Francisco and Monterey's early residents had left those areas and migrated to Santa Clara Valley.

"I thought this was so intriguing. I wanted to continue finding out about these people who migrated," she said.

Adkins said she spent countless hours sorting through black newspapers published in San Francisco to piece together details about these early residents. She also found many of their histories on "little sheets of paper" tucked away in boxes stored in libraries and the county archives. For her Santa Clara County research, she tracked down descendants for as many of the area's original families featured in the book as possible. In some cases, she searched for two or three years to locate ancestors, she said.

Adkins said these African-American families came to Santa Clara County during various migration waves.

"Their challenges were about the same, but the reasons for coming were different," she said.

Adkins said she learned that Santa Clara Valley was a very attractive place for early settlers who came out from the Midwest and south looking for new opportunities prior to 1940.

"They wanted to work in agriculture or have their own farms and businesses," she said. "Santa Clara Valley was considered a prime agricultural place."

Adkins said the number of early African-Americans living in Santa Clara County was small, but those pioneers created opportunities for the next generation.

"They overcame great odds of slavery, racial discrimination and economic struggle," she wrote in the book's introduction. "They ultimately developed communities with churches, businesses, schools and and social and cultural organizations ... that still exist throughout Santa Clara County today."

Sam McDonald Park, the 967-acre open space preserve in neighboring San Mateo County created on a portion of property that McDonald bequeathed to Stanford for use as a park for children, is among the monuments that still stand today.

What: Author Jan Batiste Adkins will talk about her new book "African Americans of San Jose and Santa Clara County."

Where: Mitchell Park Community Center, El Palo Alto Room, 3700 Middlefield Road

When: Sunday, March 3, 2-4 p.m.

Cost: Free.

Info: Go to pahistory.org/programs.html.

Adkins will sit down with Palo Alto Weekly journalists to discuss her book on an episode of "Behind the Headlines." A link to the show will be posted here, on its YouTube channel and podcast page.

Comments