There's something about marijuana that makes even the most enterprising cities procrastinate.

Consider Palo Alto, where — with the looming legalization of recreational-pot sales on Jan. 1 — the City Council is preparing to approve later this month a moratorium on pot dispensaries. This will be the second time in two years that the council will pass such a ban — the first is set to expire in November.

It's not that Palo Alto council members hate marijuana — a position that would make them a minority in a city where two-thirds of the voters supported Proposition 64 last fall. It's just that they'd rather put off answering the question that every municipality is now wrestling with: How do we feel about having pot shops in our city?

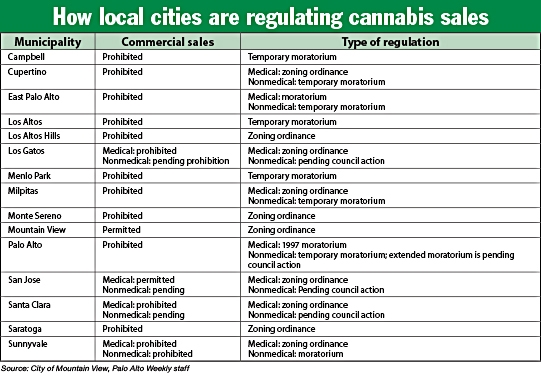

Palo Alto is one of many Midpeninsula cities taking a conservative, wait-and-see approach. Since September, Menlo Park, Cupertino, Woodside and Sunnyvale have all adopted anti-pot ordinances, an action that Palo Alto is scheduled to consider on Oct. 30. Los Altos and Milpitas adopted bans on sales and cultivation of recreational marijuana earlier in the year, while Sunnyvale and Los Gatos are revising their zoning codes to prohibit commercial marijuana activities. Campbell voters went to the polls in April to approve a council-backed measure that bans dispensaries at least until April 1, 2019.

The defensive municipal crouch may seem a bit odd, given the popularity of Prop. 64 and the general enthusiasm among local officials for decriminalization of marijuana. Palo Alto Councilman Cory Wolbach, chair of the council's Policy and Services Committee, referred to the drug war as "fraudulent" during a discussion last year.

He told the Weekly recently that he considers it tragic that so many people are arrested and have their lives turn upside down and their families torn apart because of drug laws. But when asked about the prospect of allowing marijuana dispensaries in Palo Alto, Wolbach had to pause.

"I'm not sure I'd want a pot shop in my neighborhood," Wolbach said.

While current council members are ambivalent about marijuana, city leaders have a history of snubbing their nose at pot. In 1997, the council voted to ban medical-marijuana dispensaries. And in 2012, the Palo Alto council took a unified stance against a citizen petition to allow up to three medical-marijuana dispensaries and to impose a 4 percent tax on gross receipts.

At the time, Greg Scharff and Liz Kniss (now the city's mayor and vice mayor, respectively) were part of a group of officials who co-signed a ballot argument against Measure C that described medical-marijuana dispensaries as "hotspots for crime," claimed that cities with dispensaries have experienced "an increase in crimes such as burglary, robbery and the sale of illegal drugs" and argued that allowing and taxing up to three medical-marijuana dispensaries would "increase marijuana use by our kids and it will hurt them physically and academically."

"The biggest threat to our children and our community is to blur the line between dangerous, illegal drugs and medicine," the argument stated (the ballot measure was overwhelmingly defeated).

With the passage of time, however, City Hall's position on marijuana has become both less shrill and more opaque. Recent public hearings on marijuana policy barely mentioned the issues that dominated the discussion in 2012: crime, health and illegal sales.

Scharff acknowledged his view on marijuana has shifted somewhat. Like Wolbach, he said he supported Prop. 64. He also noted that some communities now have dispensaries that are "clean, well-done and look great" — a departure from his 2012 depiction of these businesses as "hotspots of crime."

The council's more recent conversations on marijuana policy have been relatively brief, with few public comments and little disagreement. In general, members have deferred to advice from the City Attorney's Office, which amounts to a "ban now, revisit later" approach. Strikingly, the council's usual appetite for being at the head of the pack on all things green — whether carbon-neutral electricity, zero waste or solar panels — goes out the window when marijuana comes up.

"Palo Alto doesn't seem to have any enthusiasm to be leader on this issue," Wolbach told the Weekly.

Waiting for state guidelines

The general reticence of some — though not all — Midpeninsula city councils stems in part from the fact that the state has yet to actually finalize marijuana regulations.

With less than three months until recreational-pot sales become legal, the California Bureau of Cannabis Control is preparing to release next month its guidelines for such dispensaries, with the expectation that it will start issuing licenses to these businesses on Jan. 1.

According to Alex Traverso, spokesman for Bureau of Cannabis Control, the guidelines will contain specific regulations on locations of dispensaries, hours of operation, security requirements and cannabis quantities, among others.

Some of these are already addressed in Prop. 64. For instance, the measures requires marijuana retailers to implement security measures that prohibit people from remaining on a dispensary premises if they're not engaging in an "activity expressly related" to the dispensary's operation; to have areas accessible only to authorized personnel; and to store all marijuana products (other than the limited amount used for display) in a locked room, safe or vault. Dispensaries will also be prohibited from setting up shop within a 600-foot radius of a school, day care center, or youth center (cities can specify a different radius) and from allowing anyone under 21 on site.

Yet Prop. 64 also charges the Bureau of Cannabis Control (formerly known as the Bureau of Medical Marijuana Regulation) with coming up with specific regulations in areas like transportation-safety requirements and special licenses for nonprofit dispensaries.

Given that the agency has yet to release these guidelines, staff from Palo Alto's City Manager's and City Attorney's offices argued at recent hearings that unless the city adopts a local ban now, it will lose the power to control its own destiny on marijuana. Dispensaries will get licenses, set up shop and get grandfathered in, the thinking goes, so that even if the council decides at a later date that it hates marijuana shops, it will be too late to do anything about them.

"A lot of our thinking is driven by the Jan. 1 deadline, where we sort of lose some of our authority," City Manager James Keene said at the June 13 meeting of the Policy and Services Committee, which concurred with his view and recommended extending the city's original October 2016 ban.

The Sunnyvale council followed similar logic when, after a brief discussion, it voted unanimously on Sept. 26 to ban commercial operations in its city. Things are so in flux when it comes to state law, Councilwoman Nancy Smith said during the discussion, that if the council didn't adopt a moratorium, "Our local ordinances would be pre-empted."

"We're doing this because we want local control," Smith said.

No reservations in Mountain View

Ken Rosenberg has no such reservations. The mayor of Mountain View proudly announced on Sept. 19 that he was one of the 68 percent of city residents who supported Proposition 64. At that meeting, the council agreed that, rather than banning dispensaries, the city should amend its zoning code to permit and regulate commercial marijuana activity.

It would be odd, Rosenberg said, for a city to vote favorably for the proposition and then "turn away from it."

"Mountain View is known for its leadership on all sorts of different issues, and I can't see why we wouldn't be on this issue as well," Rosenberg said at the Sept. 19 meeting.

His colleagues largely supported his position. Councilwoman Pat Showalter said the council would be "shirking our responsibility" if it acted as if marijuana wasn't legalized. Vice Mayor Lenny Siegel said he sees in marijuana dispensaries an "opportunity" to reinvigorate Mountain View's commercial areas. The city, he said, has been struggling to attract retail to some of its major shopping districts. He proposed making zoning changes to allow dispensaries in downtown Mountain View, the San Antonio Road area and some sections of El Camino Real.

"To me, this is a setting people should be able to go to after their dinner and dessert in downtown Mountain View," Siegel said. "To me, it's socially acceptable in this area, and we shouldn't pretend otherwise."

Mountain View isn't the only city eyeing the potential revenue of legalized marijuana. Earlier this year, the Campbell council reacted to Measure B — a citizen initiative that would have legalized and taxed up to three marijuana dispensaries — by placing two competing measures on the same ballot: Measure C, which would ban dispensaries until at least April 1, 2019, and Measure A, which would institute a 7 percent tax on gross receipts from any marijuana business operating within city borders, including delivery services and manufacturers. In April, city voters approved the two measures backed by the council and rejected Measure B. So while dispensaries won't be coming to Campbell for a while, the city expects the tax to bring between $130,000 and $260,000 annually to the city's General Fund.

Santa Clara is also exploring the economic benefits of allowing and taxing marijuana. During its Aug. 22 discussion, members of the City Council expressed some concern about allowing commercial growers in the city. Dispensaries, however, should be allowed and highly regulated, council members said.

Vice Mayor Dominic Caserta argued that a moratorium is the "wrong way" to approach the issue and pointed to the fact that 60 percent of the city's voters backed Prop. 64 — a proportion that he said amounts to a "landslide."

He supported allowing dispensaries, tightly regulating them and ensuring that none are located near schools or other facilities with children. Even though Prop. 64 already prohibits marijuana businesses from operating within 600 feet of such facilities, Caserta proposed possibly raising the buffer zone to 1,000 feet. The goal, he said, is to capture the revenue potential of this fledgling industry.

"It's happening in our city illegally, so let's make it legal," Caserta said.

Carlos Romero, a member of the East Palo Alto City Council, also argued that his city should consider the financial advantages of keeping marijuana legal, including eligibility for state grants that could be used for drug-prevention activities for youths. One idea that he floated during a July 22 meeting is limiting the number of dispensaries to one or two in his city of 30,000 residents.

Like Caserta, he acknowledged that marijuana is already being grown and smoked in his community.

"I know for a fact that when I bike down our streets or have barbecue in the back of my yard or go to MLK Park, I at times am surrounded by pot, by the smell. ... If we do use it recreationally, I think we may seriously want to think about whether or not we should allow the sale of it," Romero said.

East Palo Alto Mayor Larry Moody agreed. The cannabis movement has gained so much momentum, Moody said, that you "can't ignore the economics associated with it." He also pointed to cities such as San Jose and Oakland, which have collected $2 million and $4 million in revenues from their respective marijuana dispensaries, Moody said.

"I'm optimistic that part of the way we get in front of this is to provide some leadership around creating dispensaries in this community," Moody said.

Palo Alto supports delivery services

Palo Alto, meanwhile, is quite content with following other cities' leads. Though the council's Policy and Services Committee briefly discussed a future tax and requested that city staff come back with more information, city leaders are loathe to roll out the red carpet on University and California avenues for marijuana dispensaries. In an interview this week, Scharff noted that the city has recently adopted bans on cigarette smoking in parks, public plazas and on the sidewalks of downtown and California Avenue. For the same reason, having marijuana smoked in the city's commercial areas "does not have a good feel to it," he said.

Unlike council members in Mountain View and Santa Clara, Scharff believes that most residents in his city don't want dispensaries in prominent downtown areas — their support for marijuana legalization notwithstanding.

The goal of the council's dispensary moratorium, he said, is not to deprive people of pot. In fact, the council explicitly excluded delivery services from its prohibition on marijuana activities, he said, in recognition of the fact that some people rely on pot for medical reasons. Vice Mayor Liz Kniss, who in 2012 co-signed the anti-Measure C argument, made a pitch for not prohibiting delivery of medical marijuana at the Policy and Services Committee's June meeting. At that time, Kniss called marijuana a "very important pain reliever for someone who is ill."

"I wouldn't want to prohibit that ability for us to have deliverance," Kniss, a former nurse, said.

Scharff told the Weekly that as long as the city allows deliveries, anyone in Palo Alto who wants to smoke marijuana will be able to obtain it. On the question of dispensaries, however, he said he would prefer to see how the situation plays out in places like Mountain View, and then Palo Alto can devise measures appropriate for dispensaries in the city.

For now, he said, "If people really want to go to one, they can drive down to Castro Street."

Pot advocates: Forget local control

Not everyone is pleased with local cities' the cautious approach to marijuana sales and distribution.

East Palo Alto resident Andrew Boone has been attending public hearings in recent months to encourage council members not to move ahead with bans, temporary or not. To date, the Midpeninsula cities' approach to marijuana has been "discouraging," he said.

Boone said he became interested in the topic in 2014, when San Jose revised its regulations on medical-marijuana dispensaries. The new requirements dropped the number of dispensaries operating in the city from more than 70 to 16 — a change that he deemed unwise.

"To keep marijuana on the unregulated market is, I think, very irresponsible and to just assume that it doesn't create any secondary problems — like street vending of marijuana — is short-sighted," Boone said.

Today, the biggest distinction that Boone has seen between cities pursuing pot bans is between those that support blanket bans on all marijuana operations and those, like Palo Alto, that look to carve out an exception for delivery services. Banning delivery of marijuana, he said, is both cruel and unenforceable.

"The industry is going to take root somewhere — might as well be in our cities," Boone said.

John Fredrich, a Palo Alto resident and former City Council candidate, believes his hometown should avoid local regulations altogether and defer to the state. The council's recent moratoriums, he said, are just a stalling tactic. And its "local control" argument is just a cover for a prohibitionist mindset, Fredrich told the Weekly.

Fredrich said he was particularly upset by the council's decision last year to ban outdoor growth of marijuana — a power that Prop. 64 explicitly grants to municipalities. (Cities cannot, however, prohibit people from growing up to six plants indoors for personal use.)

Given that state law already limits outdoor growth to secured spaces that are outside of public view, the council's vote was both counterintuitive and needless, he told the Weekly.

"If it's in your backyard, behind a locked gate, you should be able to legally grow it outdoors," Fredrich said. "I don't think bands of marauders are roaming our neighborhoods looking for a couple of plants in a backyard."

Comments