In "Mendocino Fire," the title story in Elizabeth Tallent's newly released collection, a young and impressionable tree-sitter named Finn takes a false step during an occupation. Falling through the air, she "feels a pair of wings flung out from her shoulder blades, beginning to beat." As she falls, she sees a vision "commensurate with terror" of time slowing down and expanding, "wrapping terrified awareness in a confounded calm, because the tree tells her There is time."

"So she's not afraid -- fear is a kind of error stripped from her brain, and what she feels is that she's been taken in by an element so sumptuous she repents, falling, of the waste and foolishness that have constituted her relation to time. Finn falls within this sense of cradling infinity and what will later strike her as the deepest truth about falling, the thing she will never confide to anyone, is that she was curious. More mortally aware than ever before, thus more profoundly curious."

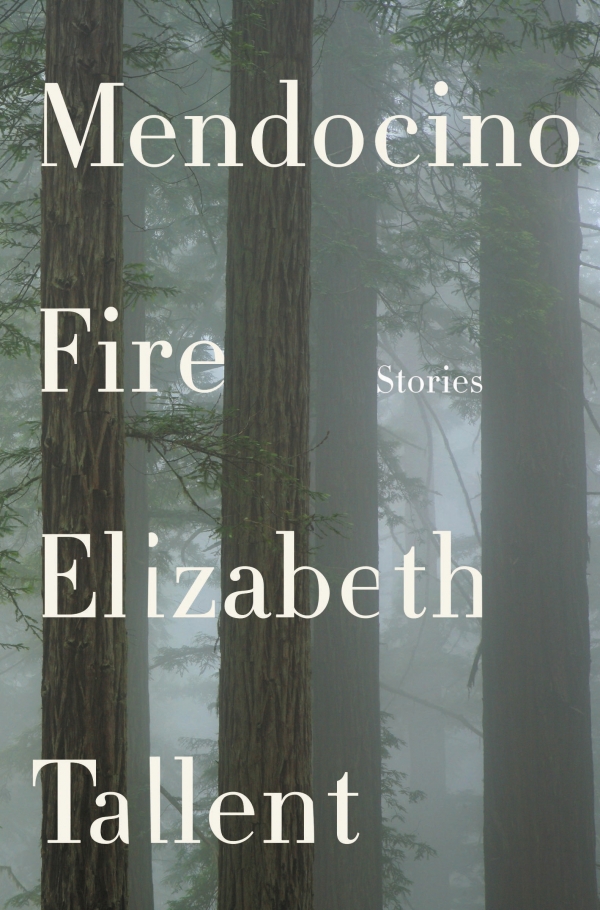

Such moments -- calm and urgent, terrifying and profound -- are scattered throughout the 10 masterful stories that make up "Mendocino Fire," Tallent's first published short-story collection in more than 20 years and a nominee for the PEN/Faulkner award (winner be announced on April 5). Tallent, who teaches creative writing at Stanford University, has published these stories over the past decade and a half in Tin House, The Threepenny Review and ZYZZYCA. Over the years, some have appeared in literary anthologies. Brought together, they reaffirm Tallent's position as a master of the form and a nuanced depicter of those intense moments when lives and relationships start to fall apart.

The protagonists in these stories, much like the settings, vary widely: young and old, brainy and brawny, fishermen and mill workers, hippies and literati. In "The Wrong Son," the first story in the collection, young Nate takes over the family's fishing boat, Louise, after his drunk and demanding father suffers a heart attack. As Nate leans over to toss a bucked of trash overboard, a wave hits Louise and Nate finds himself "shrugged off" into the water and has a vision of "fish guts unknitting a bumbling cloud." Nate, whose tense relationship with his father is roiled by feelings (mutually held) of his general inadequacy, finds a moment of clarity as he surfaces and watches another wave approach.

"He strove against the cataract and lost, borne backward into a trough rolling with echoes, and despite his setback he felt his body coming back after long years' absence, gathered and intent and smoothly useful, his soul right here too, brilliantly distinct, a thing that could be turned from him, and he wished to cradle and save it, his soul, and to do that he had only to swim, he who for once wholly aligned with necessity, rejoicing in the clear, clear light of live or id, taking pleasure in his strength, giving a stinging outline by the cold, stroke, breathe, stroke narrowing in on what he needed to do next, which was to swim around and take hold of the rungs and climb."

These moments of calmness in danger often mark a transition point for a character going through a crisis, whether it's a failed relationship or, as in "The Wrong Son," a family rift. In the story, "Nobody You Know," a woman obsesses over an ex-husband who has found a new lover. She vacillates between curiosity and detachment ("Divorce is not linear. One morning there is peace of mind, the next there is wrath") before traveling to Iowa to insert herself into their relationship.

A similar love triangle is at play in "Tabriz," where a rumpled, twice-divorced environmental activist named David faces a marriage crisis when he discovers that his new wife is a Republican (How, he asks himself in a fit of rage and confusion, can he have sex with someone who wants to drill for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge?). Furious, he watches his stepson hanging from the branch of an apricot tree and, hearing the boy's shriek, loses his footing and "in a slow-motion trance of remorse went over backward."

"With this shriek ringing in his ears David lost his footing in a slow-motion trance of remorse went over backward. Falling, he seemed to view himself from above, and if he was helpless, his arms flung out and his mouth gaping, the back of his head about to connect with the floor, he was also suspended in a peaceable realm that had detached itself from terror. David had time to marvel at this double consciousness before the impact slammed it out of his skull."

This "double consciousness" features in nearly all of Tallent's stories, as characters love, hate, fight, reunite, break up, have affairs and reflect on their roles as both an object involved in the plot and a subject examining the object's action. The duality is most explicit in "Narrator," a first-person story in which a nameless protagonist, a writer in her 20s, explores her complex and evolving feelings toward a famous writer after she sees him rudely turn his back to two women at a party. Given the warmth she felt in his writing, the narrator feels betrayed by this gesture.

"How could narrators so prodigal in their empathy originate in the brain of that withholder?" she asks.

But much like in "Nobody you Know" (and every other story), love and hate are nuanced and fluid concepts, as uncomfortable as they are essential. Like Tolstoy's unhappy families, each broken relationship in "Mendocino Fire" is unhappy in its own way -- wrought by its distinct aches and anxieties. " In three of these 10 stories -- "The Wrong Son," "Briar Switch," and "Mendocino Fire" -- the central conflict is between a parent and a child. In "Narrator," it's the flickering love between the young woman telling the story and the older writer with whom she has an affair. At one point, as she reflects on her actions, she consults the bible of all society novels: George Eliot's "Middlemarch."

"Whenever I went back to Eliot's novel, I imagined the magnanimous moral acuity with which the narrator would have illumined a theft like mine, bringing it into the embrace of the humanly forgivable while, at the same time — and how did Eliot manage this? — indicting its betrayal of the more horrible self that, in her narrator's eyes, I would possess."

This tension between guilt and self-forgiveness also runs through "Briar Switch," where an estranged daughter is driving through a snowstorm to get to her father's bedside. Her love for her father, like Finn's and Nate's for their respective parents, is strained and demanding ("not linear," as a Tallent character might say).

"Was it not just some gift allotted to you, was it finally your job to love that way, should she have fought harder against her own hard-heartedness to still be able to love like that, how serious was her crime in not calling for the two years?"

Also pondering the nature of love is Prof. Clio Mitsak, a Virginia Woolf professor who is the central character in "Eros 101."

Written in a Q&A format, the story traces the brief affair between Clio and a red-headed adjunct named Nadia. As they kiss in the bathroom during a faculty diner party, Clio ponders the nature of seduction.

"This eyes-open kiss is clumsy: neither body nor soul can really forgive that. Seduction, it turns out, requires an almost Questioner-like detachment to ensure grace. To become a character in the story is to fall from grace."

Many characters in "Mendocino Fire" fall from grace, Some, like Clio, with relish. Happily, same cannot be said for these stories.

Comments