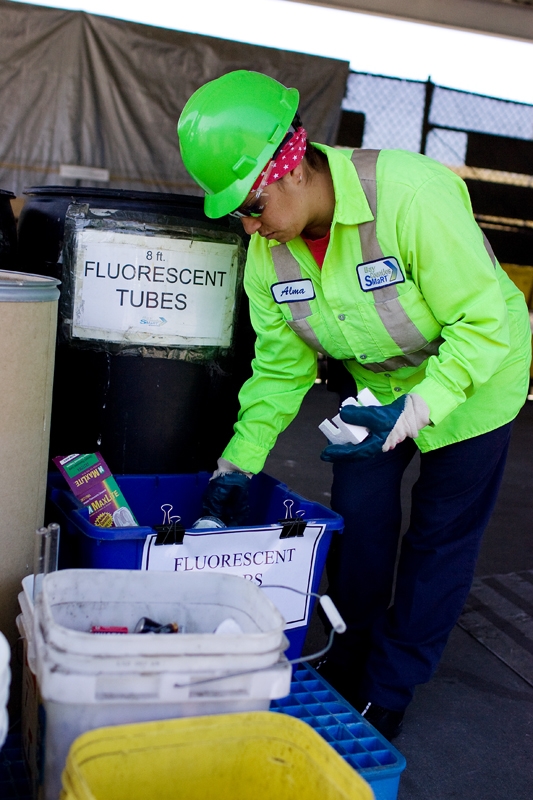

The SMaRT Station in Sunnyvale is a labyrinth of loader trucks, compost piles, stacked cubes of crushed cans and colossal mechanical worms called "trommels" that use their jagged teeth to tear open streams of plastic bags filled with Mountain View, Palo Alto and Sunnyvale trash.

The station, whose full name is the Sunnyvale Materials Recovery and Transfer Station, opened in 1993 -- a landmark year for California waste, according to Mark Bowers, Sunnyvale's solid-waste manager and official overseer of the station. That's when the state stiffened its regulations for landfill operations, prompting cities throughout the state to shut down their decades-old landfills and start thinking regionally. Palo Alto, Mountain View and Sunnyvale decided to pool their resources and open the SMaRT facility, where crews of workers stand in front of conveyor belts and salvage recyclable items from a stream of trash.

The size of the garbage piles at the SMaRT Station has generally grown and shrunk with the local economy. After peaking in 2000, during the dotcom boom, trash tonnage plummeted because of declining commercial activity, Bowers said. Between 2001 and 2002, tonnage at the SMaRT station dropped 16 percent.

Last year, the slumping economy once again lightened the trash loads at garbage dumps and sorting stations in the Bay Area and throughout California. In cities around Palo Alto, the garbage tonnage shrunk by an average of 14.4 percent, according to a recent report from Palo Alto's Public Works Department.

In Palo Alto itself, the drop has been even more precipitous -- a fact that, on one hand, has cheered environmentalists and, on the other, is resulting in a financial debacle for the city.

According to Public Works, the city's total garbage tonnage fell from 63,325 in fiscal year 2007, to 56,427 in 2008, to 35,426 in 2009 -- a 44 percent drop over two years. That decline could rightly be interpreted as resounding proof that the city's "Zero Waste" program is working and that customers are becoming more conscientious about recycling and composting.

It can be attributed in part to the city's $96 million contract with GreenWaste Recovery, Inc., which it signed in October 2008. The eight-year agreement, which has an option to extend, includes an expanded list of items residents can recycle (plastic toys, lawn furniture, cell phones, etc.) and a new program for picking up organic waste from commercial customers.

"The major gain is really in the commercial sector," Public Works Director Glenn Roberts said at the time, referring to the organic-collection service, which debuted in July 2009.

It didn't take long for local businesses to start using the new composting service.

"Businesses were very eager. Everyone was waiting for this and some people wanted to get started as soon as possible," said Scott Scholz, GreenWaste's environmental outreach manager.

It's no wonder. By participating in the new compost program, which is free for most businesses, companies were able to dramatically slash the amount of garbage they sent to the landfill -- and more importantly, the amount of money they paid the city to pick up their trash.

But green leadership in Palo Alto is ironically leading to a financial disaster. This spring, just as the City Council Finance Committee was putting the finishing touches on the city's 2010 budget, members were shocked to discover that the Refuse Fund's revenues were $8.1 million below projections. The main driver for this trend has been the commercial sector, where revenues fell $4.7 million short of expectations.

The trend prompted Councilman Greg Scharff to observe at the July 6 meeting that "Zero Waste is equaling zero dollars" and that the city's method for pricing its collection services is "crashing and burning."

The reasons for the system's financial implosion are both historical and self-inflicted. The city is currently locked into several long-term waste-management contracts, including one with the SMaRT Station and another one with the Kirby Canyon Landfill in south San Jose, the final destination for most of the city's garbage.

Both contracts were signed almost two decades ago and will remain in effect until 2021.

The contract with Kirby Canyon Landfill is a "put or pay" contract, which requires the city to deliver a specific amount of waste to the landfill per year or pay Waste Management, the company that owns the landfill, for every ton that falls short of the annual commitment.

The city paid $171,283 to Kirby Canyon in 2009 for the 4,739 tons of trash that didn't get delivered to the landfill. This year, the city will have to pay the landfill an estimated $648,218 for the 17,633 tons of garbage that won't be deposited there, according to a Public Works estimate.

Those numbers are expected to remain in the $650,000 to $700,000 range for each year the contract is in place. If the city implements mandatory composting and recycling, further decreasing the trash flow, that figure could increase by $200,000, according to Public Works. Add a waste-to-energy plant in the Baylands, and the number goes up by another $350,000-$400,000 (see sidebar).

At the same time, the city maintains its own landfill, which cost the city about $3.5 million to operate in the last fiscal year and is, according to Public Works staff, more than 98 percent full. It accepts residential garbage, compost and recyclable goods and is scheduled to close down in the next two years.

The facility currently duplicates some of the services the city receives from its SMaRT Station contract, including the drop-in Recycling Center and composting service.

"We're double paying," City Manager James Keene said at the July 6 meeting of the Finance Committee. "We're paying too much to operate the landfill, and we're not getting the value out of our contracts with SMaRT station and Kirby Canyon."

Keene told the Weekly that the city's "legacy" contracts are products of a bygone era in which city officials were more concerned with finding space for local garbage than about reducing it in the first place. Twenty years ago, as California tightened regulations for landfills, municipalities across the state started worrying about growing garbage flows and the lack of space to house it.

Many cities, including Palo Alto, found relief in long-term contracts that guarantee storage space for local waste. Under its agreement with Mountain View and Sunnyvale, the city picks up 24 percent of the cost for SMaRT Station operations.

Since then, times and attitudes have changed. Rather than worrying about where to send its garbage, many cities are now focused on reducing their tonnage -- a change in behavior that the long-term contracts and provisions such as "put or pay" failed to take into account.

"We have this sort of contract in place, and yet since then we have launched, as a state and as a society, a real movement to reduce our waste stream," Keene told the Weekly. "The movement runs contrary to many of these decisions and agreements that have been made over the years."

During recent interviews and Finance Committee meetings, city officials have stressed how unsustainable the present system is. Keene compared the present waste-management system to a restaurant that repeatedly slashes its prices until its patrons essentially get a free lunch.

"The restaurant gets full, but the model is obviously not sustainable," Keene told the Weekly. "I think at some point in time, we're going to have to look at ways to build in the cost for recycling itself."

The latest garbage trends have also introduced to the city a legal risk. Public Works' Roberts told the council members that with current rates and levels of service, the Refuse Fund is projected to drop to near zero at the end of the year. This would put Palo Alto in direct violation of state law, which requires the city to have $6.1 million in reserves, to be used for the costs of closing the landfill.

"That would be a contractual violation," Roberts said. "We're trying to take action to avoid that prospective problem."

The loss of funds and the state mandate has led to a vigorous debate among council members over the past month about how to maintain the reserve and how to reform the city's waste-management system to make it financially viable.

Now, the city's waste-collection model is on the cusp of a complete overhaul. Residents and businesses will likely see their refuse rates increase in October and, at the same time, see reduced services and higher fees at the city-owned landfill in the Baylands.

The Public Works Department is revamping the city's revenue-forecasting model, which has been completely discredited by the staggering gap in the Refuse Fund. The current model is "simplistic and unable to capture the diverse elements of our system," said Rene Eyerly, Palo Alto's solid waste manager. The new model will have more than 100 variables and will allow the city to better project the shifts in customers' behavior, she said.

Public Works is also working with consultants to rebuild the city's rate structure. A year from now, the rates will once again change and the city will almost certainly start charging residents to drop off compost at the landfill and to recycle, services that it currently provides for free.

Earlier this month, officials agreed to reduce the city's contract with GreenWaste by $800,000 this year to account for dwindling construction-and-demolition waste; reduce landfill operations from seven to five days a week, defer by a year a host of Zero Waste educational campaigns; increase all fees at the local landfill; and raise collection rates.

Despite the high costs, the city's waste-reduction efforts are expected to accelerate in the coming years. The GreenWaste trucks passing through Palo Alto bear the slogan, "Help our community reach zero waste" and the company appears to take this mission seriously. Scholz said the company plans to shift its focus to Palo Alto's multi-family complexes in the next year, which pose a particular outreach challenge because of the high tenant turnover. The company's outreach specialists plan to visit local apartment buildings and talk to residents about recycling and composting, with the goal of further driving down trash loads.

"One of the biggest changes is getting into those establishments and making connections," Scholz said.

But each step toward Zero Waste will bring a greater financial challenge. The city's goal, which the council adopted in 2004, is to divert almost all waste from landfills by 2021. The city's diversion rate was 62 percent last year, and Public Works officials estimate that it has climbed by about 10 percent since then.

One major program that the city plans to institute soon is curbside organic-waste collection for residential customers, a program Eyerly said will likely be in place in about two years. The program would further reduce the city's garbage loads, but it is also expected to drive up the city's operational costs.

Roberts predicted that climbing to the 90 percent range would become more expensive with every additional percentage.

"When you do any kind of programs designed to reduce pollution or waste, the final incremental percentages become more expensive than initial reductions," Roberts told the Finance Committee.

Palo Alto officials also hope to nudge the community toward Zero Waste by revamping the city's Recycling and Composting Ordinance. Staff initially hoped to enact an ordinance that would fine residents who repeatedly throw out large amounts of recyclables but decided to scrap the plan after residents complained about the prospect of "garbage police" sifting through their trash.

The new proposal, which staff unveiled to the council Policy and Services Committee in May, relies mainly on education for residential customers. After two years of intensive outreach, staff would consider possible enforcement mechanisms. For commercial customers, city officials plan to focus exclusively on education in the first year and to introduce an enforcement component in the second year. Enforcement would include two notifications, followed by a fine. If these have no effect, the city would curtail its garbage-collection service for the egregious violators.

The aggressive effort is expected to further reduce the amount of recyclable items in local trash, which staff estimates to be at about 43 percent. The effort's effect on the city's finances is less clear, however. Bowers, the solid-waste manager in Sunnyvale, said this dilemma is one that many cities are now wrestling with.

"If people migrate to smaller containers, fixed costs (of waste-management operations) don't just go away," Bowers said.

Unfortunately for ratepayers, this means that even if they reduce their trash loads (or, in Palo Alto's case, because they reduce their trash loads) rates are still likely to go up. Cities like Palo Alto, which can no longer afford to completely subsidize recycling, will have to find other incentives to encourage residents to recycle and compost. They will also have to communicate to their ratepayers that the prices they've been paying for their service have not been reflecting the true costs of garbage collection, including the costs to the environment.

In short, the city will have to start charging people for doing the right thing.

"We live in an area where people don't just recycle because it's a nice thing to do," Keene said. "We recognize that it's part of the changing behavior and that we have a lot of externality costs that have not been priced."

SMaRT Station officials acknowledge the costs to going green in their promotional material for the waste-transfer station. One brochure alludes to the global recycling market, which hit a major downswing in late 2008.

"We didn't receive as much revenue from the sale of this material as we have in the past because of the temporary impact of the global economic crisis on commodities market, but that disappointment is lessened by knowing that the environment benefited, even if our bottom line did not."

For Palo Alto ratepayers, that could soon be the only remaining solace.

Comments